For thousands of years humans have been faced by the animal problem as, possibly, the most demanding of all moral issues. How should we treat the other animals? The great Jain and Buddhist civilisations, for example, teach respect for all forms of life, while Christianity (since Francis of Assisi) has tried to ignore the whole subject, and for centuries the Western world pretended the problem did not exist.

History shows that progress in animal welfare tends to take place at times of affluence and peace. When humans feel threatened by poverty or war they seem only to have time for themselves; they put themselves first and speciesism runs riot. Our natural human compassion for animals is obliterated by need.

Over the centuries we have seen early thinkers and preachers being either sympathetic, opposed or silent on the animal issue. Some of those in the ancient pro-animal camp, in addition to Gautama Buddha and Lord Mahavir, have included Pythagoras (active around 530 BCE), Asoka (Emperor of India), Marcus Aurelius (Roman Emperor) and the philosophers Porphyry, Plotinus and Plutarch. So what did they say on the subject?

Pythagoras had hundreds of thousands of followers and promoted a vegetarian diet. He believed “animals share with us the privilege of having a soul” and concluded: “As long as man continues to be the ruthless destroyer of lower living beings, he will never know health or peace.” Pythagoras seemed to base his ethic upon belief in reincarnation and belief that animals have consciousness (or ‘soul’).

Plutarch was disgusted by the thought of eating meat and considered that “kindness and benevolence should be extended to the creatures of every species.” If we want meat, we should have to kill the animals ourselves, not with weapons, but with our bare hands and teeth!

Meat, said Porphyry, is sheer murder: “For the sake of some little mouthful of flesh we deprive a soul of the sun and light, and of that proportion of life and time it had been born into the world to enjoy.” Arguments such as Porphyry’s continue to this day. Indeed, they were very influential in Europe right up until the end of the 13th century.

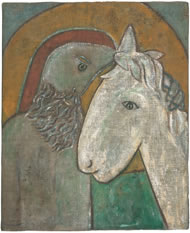

Most of the Christian saints and many monastic orders were vegetarian, or partially vegetarian. Indeed, many of the saints shared their lives with animals and there are stories about how they saved animals from cruel hunters. The saints of the Eastern Church were especially compassionate.

Then everything began to change under the influence of the early Renaissance and of church teachers such as Thomas Aquinas, whose synthesis of Aristotelian philosophy and Christianity would become the dominant teaching of the Catholic Church to the present day. Following the opinions of Aristotle (who denied moral status not only to animals but also to women and slaves), Aquinas argued that the only valid reason for treating animals with any kindness was that this tended to encourage pity towards other humans. He quit the vegetarian Benedictines and, against his family’s wishes, joined the hard-line Dominicans.

For Aquinas, only humans mattered. He became a great promoter of anthropocentrism and speciesism, his teachings blending with the incipient spirit of Renaissance humanism that celebrated human supremacy. (Not that all Renaissance men were speciesists: Leonardo da Vinci, for example, is a glorious exception.) The treatment of animals in Europe rapidly worsened from about 1300 onwards, reaching a nadir in the late 16th century. Later, Aquinas would be followed by other champions of speciesism such as Descartes, who argued that animals are unconscious machines.

It is strangely true that the three outstanding intellectual leaders of speciesism in the West – Aristotle, Aquinas and Descartes – have all been shown by the passage of time to have been utterly wrong in most of their opinions generally.

Would everything have been different if there had been no arrogant Aristotle, anthropocentric Aquinas or dim-witted Descartes? I think it probably would have been. Christianity might have developed along vegetarian lines following the dictates of St Benedict, and the common 13th-century practice of including animals in church services would have become commonplace.

With the respect for animals that subsequently flowed from perhaps the world’s two greatest scientists – Sir Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin – it is unlikely that the modern age would have reversed this compassion. Today, in Europe, we would have had a body of law that would give equal standing to animals of all species. So, causing X amount of suffering to a dog or a cat or a fox would today be regarded as being just as bad as causing X amount of suffering to a human animal. The influence of the saints, the thinkers of the Enlightenment such as Jeremy Bentham, the efforts of Edwardians such as George Bernard Shaw, Henry Salt (see Pioneers, page 36) and Gandhi, and today’s animal rights movement would have all confirmed this equality in the eyes of the law.

Darwin’s theory of evolution postulated that humans are just one species of animal among many other species. We are literally related to the other animals genetically and so, I believe, should be morally related too. The difference between us and the other animals is only “one of degree and not of kind”, as Darwin said in his book The Descent of Man in 1871.

A few years earlier, in an article attacking the cruelty of trapping animals (Trapping Agony in The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette of August 1863), Darwin had said: “An English gentleman would not himself give a moment’s unnecessary pain to any living creature, and would instinctively exert himself to put an end to any suffering before his eyes.”

How long does this tyranny have to go on? Why does it persist? As Barbara Gardner points out in her forthcoming book Compassionate Animals (to be published later this year), in the 21st century we no longer need the other animals to pull our ploughs, carry us from place to place, or provide us with clothing. So there is far less need for our speciesism.

Without the selfish trio of Aristotle, Aquinas and Descartes, the far more compassionate teachings of Buddha, Pythagoras and the Jains might have prevailed.

Perhaps they still can!