Didn’t seem like much was happening, So I turned it off and went to grab another beer, Seems like every time you turn around There’s another hard-luck story that you’re gonna hear, And there’s really nothing anyone can say...

Bob Dylan’s cosmic shrug, in his song Black Diamond Bay, was prompted by news of a vast earthquake and volcanic eruption “that left nothing but a panama hat”. Despite such early songs as Masters of War and Blowin’ in the Wind, the great singer-songwriter’s declarations of concern have always been a little capricious. But the rest of us are not much better. Even for those of us who delve deep into the more serious newspapers and have a considered opinion about practically everything, there comes a point, an issue, a story, a place that combines remoteness and strangeness and political noxiousness to such an extreme that “there’s really nothing anyone can say” about it. North Korea is one. And for a very long time Burma was another.

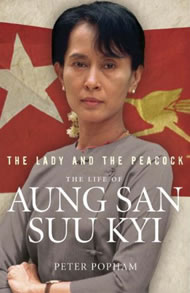

It really was the mother of lost causes. And Aung San Suu Kyi, the subject of my new biography, The Lady and the Peacock, seemed trapped inside that lost cause like a wasp in a jam jar.

I suppose I had become The Independent newspaper’s de facto lost causes correspondent when I first visited the place. I had already written about the heroic campaign of Swiss environmentalist Bruno Manser on behalf of the Penan tribe of Sarawak, the fight to save the Philippine eagle in Mindanao, and nostalgia for the British Raj in the “burned-out barrack stove” (Kipling) of Aden. Written exclusively for the paper’s Saturday magazine, my stories of doom and defiance in obscure corners of the world complemented Mark Lawson’s celebrity profiles and Amanda Mitchison’s tales of the metropolitan bizarre, and were part of the magazine’s unique formula.

But even our beloved editor baulked a little at Burma. The year was 1991. Three years before, thousands of protesters had been killed in cold blood when the military junta decided to put a lid on the pro-democracy campaign. Soon afterwards, multi-party elections were announced, Suu Kyi and her colleagues formed the National League for Democracy (NLD), and a Burmese spring appeared to be under way – until suddenly it all went sour and Suu Kyi was put under house arrest. All her colleagues were thrown in jail.

Nine months later, in May 1990, elections were duly held; the NLD won by a landslide but the regime, now known as SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council), responded by ignoring the result and arresting many of the MPs-elect. They had borrowed the tactics of Mao Zedong across the border: letting a hundred flowers bloom, the better to snip off their heads.

And it was one year after that aborted election that I went in, first visiting a jungle camp in Karen territory where a government-in-exile, which included a cousin of Suu’s, had found a home, then returning to Bangkok and flying in through the front door, visiting the tourist sites in the only way that was possible at the time, on a seven-day guided tour. We bounced around from Rangoon to Inya Lake via Pagan and Mandalay in an ancient Fokker. I had arrived at the start of the annual water festival, and everywhere we went the locals drenched us.

Getting past the festival high spirits, I had never been to a place where people were more scared or more angry. I brought a letter from an exile in the jungle to a prominent lawyer in the city centre. She read it at speed, then handed it back and ordered me out of her office without a smile. The following month – I learned about it much later – she was arrested and sentenced to 25 years in jail for her political activity. I have no way of knowing whether my intrusion was partly responsible.

At the time Suu Kyi had already been locked in her home for nearly two years. Later in the year she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, but the regime became more intransigent than ever. Great excitement accompanied her release in 1995, but within a few months it became clear that it was a cynical gesture, which the regime had no intention of following up with real reforms. Her movements were tightly restricted, her family again barred from visiting; then in 1999 her courageous and infinitely supportive husband, Michael Aris, died. The following year she was again confined to her house.

A similar cycle of hope and despair followed her release in May 2002. At the time I was The Independent’s Delhi correspondent and I flew to Rangoon to interview her. She was warm and generous with her time, but extremely diffident about the prospects for real change. And rightly so: less than a year later she narrowly survived an attempt by the regime strongman, Than Shwe, to assassinate her. She again disappeared into detention, and remained there for more than seven years, totally isolated for most of that time.

There really was nothing to be said about a regime that could do that to a woman as brave and as firmly wedded to nonviolence as Suu. It was quite literally unspeakable. But while most of us turned away from that vileness to concentrate on issues that were less intractable, the Burmese did not have that option: it was their country, their future, their destiny. However slim their hope, it was all they had to cling to, and Suu, with her calm resolve and her daily meditation practice, was its unwavering embodiment. That fact – her unique symbolic importance – was brought home to me as never before when in September 2007 the Saffron Revolution culminated in a procession of monks to her garden gate, where she emerged to greet them with palms pressed together.

We had the luxury of giving up on Burma, putting it on the back burner, forgetting all about the place. But that was a luxury neither Suu nor her compatriots could indulge. Steadfastness: that was the example she set for them. And now, almost miraculously, it is getting its due reward.