A drift at sea in a lifeboat, life is suddenly different. Should the rich passengers get bigger shares of the rations? Of course not. Money doesn’t count in a lifeboat; the situation demands a new frame. But frames can be hard to spot – unless you suddenly find yourself in a lifeboat.

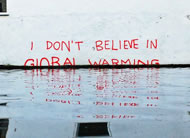

As we look forward to the Paris climate summit this December, how we look will determine what we see. And how we look at things is strongly influenced by how they’re framed.

Take economic growth, one of the major excuses to block action on climate change. Our logical brains tell us that growth can’t go on forever on a finite planet, and yet growth is so strongly framed as being both good and necessary that, for many people, to question it has become unthinkable. Some of this framing is obvious: when the economy is growing you’ll hear positive words like ‘healthy’, ‘buoyant’ and ‘good’; if not, look out for ‘weak’, ‘stagnant’ and ‘bad’. But this overt propaganda is just the beginning; deeper frames misrepresent what growth actually is. If you level off at 70 mph on the motorway, you haven’t slowed down, let alone stalled; and yet levelling off our economy is usually described in these terms, sometimes even as going backwards. Or take the phrase ‘economic recovery’. That frames a lack of growth as an illness: something you recover from. If a resumption of growth is called a recovery, who wouldn’t want it? We need to get our language straight.

Now, does framing apply to the climate talks in Paris? You bet it does. Our response to climate change is to seek international agreements on emissions. Does that sound about right? Well, it shouldn’t: that phrase, in a mere twelve words, frames the problem unhelpfully in four different ways.

First, to regard climate policy as a ‘response’ is to frame climate change as something that’s just ‘happening’. In this frame our role is to respond to it (building flood barriers, say). Asking whose fault it is, or what can be done to stop it – these both fall outside the frame. Staying in the response frame is like rearranging deckchairs on a sinking ship instead of fixing the hole in the hull: it doesn’t tackle the problem. We don’t have to respond to climate change; we have to stop causing it.

How? Well one part of the plan must be to limit or ‘cap’ the carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels. The aim shouldn’t be to agree what is politically feasible; rather, it should be to determine what is necessary and then ensure that it happens. We must reject the frame that realism means ‘political realism’, and insist that it means ‘recognising physical and ecological limits’.

Next, what about that word ‘international’? Most people unthinkingly accept the frame that portrays the world as a collection of countries. So in looking at a global problem, attention immediately focuses on national commitments, and negotiations between nations. It’s only if we look outside this ‘nations’ frame that we might think of a worldwide solution for the planet as a whole. A single, global system would bypass all the inter-national posturing and bargaining at a stroke. Global emergencies require global action: after all, it’s global warming, not international warming.

And lastly, is a focus on emissions (and hence on vehicles, power stations, and so on) a frame, by any chance? Yes: a frame that concentrates attention on the place where the emissions take place. But the root cause lies outside this frame. An ‘upstream’ focus would concentrate on the fossil fuels themselves; the same change in emphasis that underpins the divestment movement and ‘keep it in the ground’ campaigns.

Wouldn’t it galvanise the debate if the climate marches and rallies in the run-up to Paris not only harnessed the widespread feelings of public concern, but also helped to focus them into a clarion call for a specific and inspirational plan of action that broke out from the old frames? Wouldn’t it be a historic turning point if the negotiators at Paris listened, ditched the international game-playing, and adopted a single, global, fair and effective upstream system instead?

How realistic does that sound? Not very? It’s easy to feel the framing closing in again. But we can all resist. If we’re prepared and we can spot when frames are being used, that’s a powerful inoculation against them. It gives us the power to counter many of the arguments put forward by politicians and economists, and by acquaintances closer to home.

We can reject the framing of climate change as down to individuals ‘doing their bit’: a frame that distracts us from pushing for a global policy to tackle the problem as a whole. We can unmask the framing of climate change as an environmental issue; looking outside that frame, it’s clear that it will affect every aspect of everyone’s lives, whatever it is they care most about. And we can reject the frame that it’s all about money: isn’t securing a planet for our children a moral issue? Spiritual leaders typically use completely different frames from economists!

At a deep level, this can be liberating and empowering. Think what escaping from the growth frame, say, might feel like. Growth is fine for children, but adults stop growing when they reach maturity. So letting go of growth is growing up. This can be a powerful new story for our times: our species’ coming of age. Doesn’t that yield a grander sense of what it means to be human than clinging to a childish desire to keep on growing forever?

Let’s be mature about the climate situation, highlight the ‘playground thinking’ of the economists, politicians and corporations – and climate negotiators – and argue for an adult approach to tackling this urgent planetary crisis. It’s up to us to make them look reality squarely in the face – and grow up.