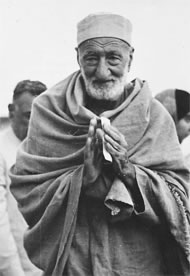

Badshah Abdel Gaffar Khan was a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi and in every sense his Muslim counterpart. Yet whereas a statue of Gandhi was unveiled in London’s Parliament Square in March this year, relatively few in the West have heard of Badshah Khan, Islamic peace warrior. A sorry state of affairs when now, more than ever, we need a Muslim peace icon.

Disarming tribal warlords with his nonviolent credo, Badshah Khan formed a weaponless ‘army’ to take on the colonisers of the Indian subcontinent, the British, and played a major role in the gaining of independence in 1947. Equally important, however, was his lifelong opposition to religious sectarianism.

Just as Martin Luther King’s Christianity was refreshingly different from that of rednecks or reactionaries – or indeed the Ku Klux Klan – it has been wonderful for me to learn more in recent years about this impassioned and courageous Muslim hero, who was still fighting for peace in his nineties and was regularly imprisoned for his political beliefs by both the British and the Pakistanis. A powerful counterweight to the stereotypes and Islamophobic hysteria currently being peddled by the West.

Abdel Gaffar Khan – the honorific title ‘Badshah’ was bestowed on him in his twenties and means ‘King of Chiefs’ – was born in 1890 to a land-owning family in the North-West Frontier Province (now part of Khyber Pakhtunkwha) of what is now Pakistan. A giant of a man in every way, he grew to a height of 6ft 5in, and would live to be nearly 100.

The young Khan was educated in a British-run missionary school and carried out his first act of nonviolent protest at 17 when he refused a prestigious commission in the ranks of the British Raj. His precocious desire to serve his people and liberate them from the yoke of imperialism saw him establish a mosque school in his hometown of Utmanzai in the Peshawar valley when he was just 20. Five years later the British closed it down.

Violent resistance did not impress Khan as particularly effective, and it went against his essentially peaceful and courageous nature. He was involved in various nationalist political movements before establishing his red-shirted Khudai Khidmatgar (‘Servants of God’) unarmed peace army in 1929 to protest and campaign against the British, pursuing the path of a jihad in which only the enemy bore swords. It was an instant success, mobilising an estimated 100,000 men and women.

The British reaction was brutal. The repression of the Servants of God saw some of the worst acts of violence committed by the Raj, including the massacre of hundreds of unarmed protesters in the Peshawar Storytellers’ Bazaar in 1930. Khan was arrested shortly afterwards and imprisoned – the first of many spells in jail under both the British and, after independence, the Pakistanis.

Working side by side with Gandhi – who called him “a miracle” – Khan shared Gandhi’s vision of Satyagraha, or active nonviolence. He promoted women’s rights and campaigned against the mounting sectarianism that would tear India apart by 1947. He became a prominent member of the Indian National Congress, and in 1931 he was asked to become its president – an honour that he refused, saying: “I am a simple soldier and a servant of God. I only want to serve.”

He was opposed to partition, which led to accusations by Islamic extremists and nationalists that he was anti-Muslim, and he was hospitalised in a 1946 attack by an unknown assailant. Gandhi, too, tried to prevent partition right up to the end; his final gambit was the proposal that Muslim leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah be made prime minister of a united India, but the Congress party voted against him and for partition. “You have thrown us to the wolves,” was Khan’s response. Gandhi was assassinated in 1948 by an extremist Hindu, Nathuram Godse, who accused him of favouring the Muslims.

Unwilling to encourage discord, Khan accepted the new geo-political status quo and pledged his allegiance to the fledgling Pakistani state in 1948; but suspicions about him abounded. Khan and his Servants of God continued to agitate for human rights and equality, and he founded the first opposition party, the Pakistan Azad Party. Acting no better than the British, Pakistani security forces shot dead hundreds of his unarmed followers in the 1948 Bhabhra massacre, and Khan was kept under house arrest (without charge) from 1948 to 1954.

In 1958 the Pakistani regime offered Khan a ministerial post in a bid to silence him. He refused and was again imprisoned, by that time aged 68. He remained in jail until 1964, when he was released for hospital treatment in Britain, after which he went into exile in Afghanistan. He was named Amnesty International Prisoner of the Year in 1962 for his example as a prisoner of conscience.

When the Awami National Party, which his son Abdel Whali founded, gained control of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa local government in 1972, Khan returned to Pakistan. He was then 82 years old. His declaration that the government of Pakistan’s then prime minister, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, was “the worst kind of dictatorship” saw him briefly jailed again.

Khan died under house arrest in Peshawar, Pakistan in January 1988 and 200,000 mourners attended his funeral, including the Afghan president, Mohammad Najibullah, and the Indian prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi (who defied attempts to prevent him doing so by the Zia ul-Haq regime). The Indian government declared a five-day period of mourning in Khan’s honour. This was no obscure figure to be quietly dropped into the dustbin of history.

Badshah Khan was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, and while many Pakistanis remain ambivalent about him, his achievements and legacy were officially recognised in India, where he was given the highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna prize, in 1987. In recent years there has been something of a reawakening of his legend, and in 2012 Peshawar International Airport was renamed Bacha [Badshah] Khan International Airport.

In the West, Badshah Khan remains an obscure footnote to the Gandhi story. Perhaps a Muslim peace hero would not be widely welcomed, given the prevailing climate in which the Muslims have replaced the cold war Communists as the new enemy, the ‘other’, terrifying, brutal, ruthless and alien. This image, which finds its apotheosis in Islamic State (ISIS), has been propagated to the extent that the notion of a peace-loving Muslim has become oxymoronic, while peace-loving Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and Jews abound.

War is a lucrative business, and in the absence of a tangible enemy the War on Terror (read ‘Islamic extremism’) keeps the global arms industry – currently worth US$1.3 trillion a year – in clover. A kindly, gentle, avuncular Muslim leader like Badshah Khan does not sit easily with this monetised rewriting of history.

Sectarianism fragments and dilutes Islam and lies at the heart of the current chaos across the Middle East. Badshah Khan fought against sectarianism, and the movement he pioneered was inclusive and tolerant. But what a formidable force the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims would constitute if they were united. Would Israel continue to steal land belonging to the Palestinians and attack the imprisoned people of Gaza with impunity in the face of such a moral army? Would Western companies continue to extract the profits from the region’s natural resources, which could be used instead for the benefit of its people? Would there be any further need for the region’s gargantuan defence spending?

It is my hope that, in rediscovering Badshah Khan, the Muslim world will reclaim its own peaceful role model: an Islamic icon, the Muslim Gandhi.