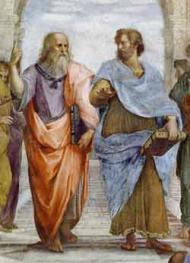

Nearly two and a half thousand years ago Plato and Aristotle had a momentous disagreement about communes and the commons. In Book Five of the Republic (Plato’s biggest, boldest work) the main speaker, Socrates, advocates the abolition of the conventional family and the institution of communal arrangements for the begetting and rearing of children. The reasoning behind this daring fantasy has nothing in common with the 1960s’ spirit of ‘letting it all hang out’. Plato believed that the family, private property, and ownership in general, foster clannish self-interest; these alternative arrangements are intended to do the opposite and promote “a universal feeling of sympathy” in which the greater good of the whole community takes precedence over individual whim.

Republic Book Five famously inspired Aldous Huxley’s dystopia of slavish, mindless hedonism, Brave New World. But long before that it was roundly criticised by Plato’s greatest pupil. Aristotle, with what seems like unanswerable reasonableness, dismissed Plato’s ideas as simply impractical: “That which is common to the greatest number”, he writes in Politics, “has the least care bestowed upon it. Every one thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest; and only when he himself is concerned as an individual.” In a striking phrase, Aristotle suggests that in Plato’s ideal state, “love will be watery…How much better it is to be a real cousin of somebody than a son after Plato’s fashion!”

Like so many of today’s mainstream economists and politicians, Aristotle defends the claims of private property and family values: people, he argues, can only really love and care for what they own or have an intimately personal stake in. The ecologist Garrett Hardin (apparently without having read Aristotle) developed this view in his pessimistic essay The Tragedy of the Commons. Hardin argued that land and other resources held in common were doomed to over-use and degradation.

Maybe it sounds far-fetched, but I suspect that many of the root-causes of the current environmental crisis can be found in the way this debate was framed - and what was left out of it. Neither Plato nor Aristotle - nor Hardin - had a broad enough view of either the commons or the environment. (There isn’t really a word for the environment in ancient Greek.) They all missed things out, in various ways, but Plato the unfashionable proto-communist was on the track of something big and important.

Where did Plato go wrong? At a key moment in Book Five of the Republic, Socrates declares “that city is best ordered in which the greatest number of people use the expression ‘mine’ and ‘not mine’ of the same things in the same way.” There is a noble intention behind this: that the sufferings of any citizen should affect all citizens. But what may be wrong with the choice is the personal pronoun. Neither Plato nor Aristotle nor Hardin seems able to move beyond ‘mine’ and ‘yours’ -the limits of property ownership - to ‘ours’.

Plato and Aristotle frame their discussions of community and the commons in terms of the polis, the Greek city-state. The best that can be hoped is that things may be well ordered at that level - but even that might be a hope too far. Neither the idea of a globally interdependent network of states and economies, whose welfare was interlinked, nor the realisation of threats to the over-arching life-support systems of the Earth had yet dawned.

Perhaps the big things that are ‘ours’ - the air we breathe (if it’s breathable), the sun and the sky (if a nuclear winter has not obscured them), the unfathomable oceans (if they haven’t been fished out), the rivers (if they are still flowing), the biodiversity of the Earth - still seemed so vast, in the 4th century BCE, that they could be taken for granted. Our challenge, it seems to me, is not so much to foster a shared feeling of ‘what is mine’ as to recapture the sense of ‘what is ours’.

This is why we need to pay more attention to the historians and writers, from E. P. Thompson and Norman Lewis (in Voices of the Old Sea) to Richard Mabey, who have memorialised the successful traditions of common habitation and use of land of which Hardin had no idea. We will not be rescued by either Aristotle’s bland faith in private ownership or Plato’s over-drastic communism. We will only be saved if we realise how much we have in common and need to hold in common.