“Slow onset emergency” is one of the most terrifying phrases you can hear in the Oxfam offices. Tsunamis and earthquakes scare us all, but the threat of a gradual, developing crisis like that posed by the El Niño weather system raises a different fear – that we will see suffering in slow motion. It’s hard to raise the alarm that millions of people face drought and hunger when the crisis builds cumulatively. Yet failed harvests that push families into poverty, communities forced to leave home, and conflict over limited resources all combine to spell disaster on a massive scale. It seems that as humans we find it all too easy to sleepwalk into a catastrophe until it is upon us.

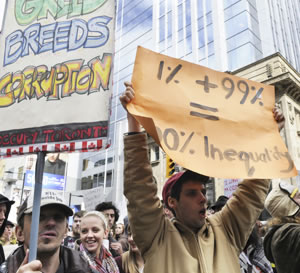

I am feeling the same now as I see the annual Oxfam reports on inequality stacked up on my desk. Three years ago we warned that the world’s richest 85 people had the same wealth as the poorest half of the planet combined. The next year, it was found that the world’s top 1% own more wealth than everyone else combined. And now, in 2016, the number of billionaires who share the wealth of the poorest half of the world is just 62.

Such growing extreme inequality is a warning sign that spells disaster for millions, as surely as any weather forecast. In rich and poor countries alike, it is holding back the global fight against poverty. Though the world has made great strides in increasing people’s incomes over the last 15 years or so, The World Bank calculates that an extra 200 million people could have been brought out of poverty had we also tackled inequality. We have always known that some people are poor while others are rich. What we increasingly understand is that some people are poor because others are rich.

Extreme inequality threatens the very notion that we are “One Humanity”. More unequal societies have been shown to have lower levels of social trust and lead to poorer health. Inequality breeds violence and thwarts gender equality and the rights of women. Extreme inequality does not just mean that someone has a yacht while someone else does not. It means that the world’s poorest people are condemned to live shorter, harder and unhappier lives and to have quite different experiences of being human.

It also threatens the idea of “One Earth”. While we all share this planet, what we take from it differs wildly. The poorest half of the world’s population – 3.6 billion people – are responsible for just 10% of carbon emissions. In contrast, the world’s richest 10% produce around half. It would take the average person in sub-Saharan Africa 180 years to register the same emissions as the average American in one single year.

Our response to these slow onset crises – of both inequality and climate change – must be to reawaken some values that have been sadly all too dormant in the last 30 years of human history: values overshadowed by the perceived virtues of individualism, competition and even the notion that “greed is good”, which have dominated recent political and economic thinking.

Our economic model has been distorted to benefit a privileged minority. In this “economy of the 1%”, wealth is sucked up rather than trickling down. We strive for ever greater growth that leaves the poorest behind, and cheer for rising GDP, but we ignore the unmeasured price we pay as we burn and chop and extract beyond our planetary boundaries. We fail to even mention the hours of unpaid work, mostly done by women, that keep us all alive and healthy. We allow an elite group to use their extreme wealth to influence governments and policies that perpetuate and increase their dominance, at the expense of the rest.

But we are not helpless. We made this economy and we can unmake it. Instead we can strive for a more human economy, one based on values of collective action to solve problems, and of responsibility to each other and to future generations.

Businesses should thrive in this human economy. But we need to shift to new models that show as much concern for workers, customers and the communities that support them as for shareholders and executive boards. That includes ensuring decent jobs for fair wages and contributing their fair share of tax everywhere that they operate.

And while this is about rediscovering lost values, it is not about going backwards. Too often new technology is feared because it will mean job losses for workers and the further accrual of wealth to those who own the machines. But technology must be a major part of a human economy. It is a great liberator and problem solver, if access can be shared.

Ultimately, a human economy recognises that economic calculations are only a part of the picture. An economy is just one way to describe how we want to live together, and values-based politics and good governance need to play a greater part.

Governments that shy away from actively regulating and directing the economy to reduce inequality and deliver sustainable, equitable growth are not being neutral: they are allowing a small group of the very rich and powerful to take control. Accountable, democratic government is the most powerful equalising force that humanity has ever invented. Nurturing, creative government is a force for cooperation and innovation. A human economy has an active government at its heart.

For a thousand years, from the Peasants’ Revolt, from the Diggers to the Chartists, from Thomas Paine to William Blake, Britain’s history is one that has championed values of fairness, challenged extreme wealth, and set out the right to a more economically equal world.

In the words of Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the Diggers, “Was the Earth made to preserve a few covetous, proud men to live at ease, and for them to bag and barn up the treasures of the Earth from others, that these may beg or starve in a fruitful land; or was it made to preserve all her children?”

To meet the challenges of the future, let us remember these lessons from the past.

Mark Goldring will be one of the participants at the Resurgence 50th anniversary event One Earth, One Humanity, One Future, at Worcester College, Oxford, in late September – for details, see

www.resurgence.org/R50event