“I was ignorant that the bean flower had such a magnificent scent. We sing the rose, we sing the honeysuckle; but a whiff from such a beanfield carries us further.”

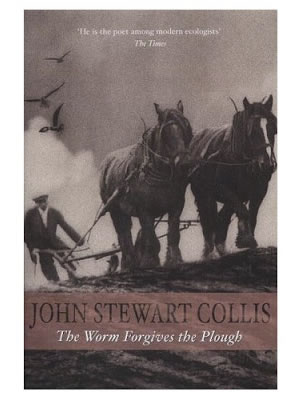

This kindhearted note typifies the tone that John Stewart Collis strikes in While Following the Plough, a memoir first published in summer 1946 that records his life as a farmhand during the Second World War. Collis, who had served during the First World War, had initially been offered an army post in 1940 and had asked to exchange it for agricultural work in support of the war effort. The book works as both a journal of daily working life and a reflection on the interplay between human labour and Nature and, by extension, the notion of what we might now term ‘wellbeing’. Indeed, it is in its ‘wellbeing’ thread of thought that the book ties in with something of the current Nature writing mode that is enjoying such popularity right now. Consider how popular Helen Macdonald’s book H Is for Hawk has proven. Certainly, the conception of Nature as a catalyst to a dynamic inner life is longstanding and predates Collis’s work: we can look to Nan Shepherd’s Living Mountain, Edward Thomas’s In Pursuit of Spring and Richard Jefferies’ Wild Life in a Southern County.

Throughout his book, Collis addresses the ebb and flow between mind and body. In the first chapter he writes: “Complete isolation with a book is Solitude, a blessed state; but isolation with physical labour can be Loneliness.” Being attentive is the condition that Collis returns to repeatedly amidst the rhythms of daily working life on the farm and, in a chapter entitled New Vision of the Field, he recalls how his increasing familiarity with a particular parcel of land makes it more real rather than less; he does not take it for granted, given its animating power: “Everyone must make a living rather than make a Life… I was not making a living at all well by jogging along here, but I could not help feeling Alive…” This is just one of many epiphanies that Collis sparks to in the midst of ordinary circumstances, and the book moves towards a concluding grand statement of his place in the bigger picture.

Collis’s memoir, then, takes us with him as he immerses himself in the ancient work of a farmer: work that involves learning to plough a furrow, to broadcast seed, to tend to the farm equipment and to harness the horses, amongst so many other jobs.

Critically, Collis isn’t concerned only with capturing the long-rhapsodised sensory pleasures of the English landscape. Rather, his recollections also serve as a lens through which to view wider issues of class and of labour. In the chapter entitled Colloquy on the Rick, Collis strikes something of a ‘state of the farming nation’ note when he comments on the perception held by city dwellers towards country people, remarking, “There are still bitter feelings on the score that the townsman looks down on them.”

Consistently, Collis moves from the specific and local to the universal and general, interrupted only when the immediate needs of farm work reel back in his big-picture thinking. The chapter Horse Ploughing crystallises this back and forth when he describes the specifics of ploughing only for these observations to ignite a feeling for the world beyond the furrow: “You seem to be holding more than the plough, and treading across more than one field: you are holding together the life of mankind, you are walking across fields of time.”

Importantly, though, Collis’s book looks in another direction, too, as it wrestles with some of the tensions present in modernising 20th-century life, and in this way perhaps Collis evokes the tradition of John Clare as he measures the changes to an ancient way of life and work. In chapter seven, he describes the agricultural labourer conquering Nature through mechanical know- how that manifests most powerfully in the introduction of the combine harvester, about which he writes in the chapter entitled The Combine Harvester; The Leisure State. There’s something rueful in the words when he notes the irony that “There are few subjects harder to think out than that of machinery… The machines have evolved in the country as naturally as flowers.”

Collis’s writing resonates somewhat with the current moment and the question of how we might think about rural working life more broadly in a world so focused on the urban experience. Indeed, in this he anticipates the recent popularity of The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks.

While Following the Plough artfully dovetails a record of Collis’s evolving understanding of farm labour with the shape of his more essential thinking and feeling. In doing so, he shuttles back and forth between what Mark Cocker, the author of Crow Country, described in a 2015 New Statesman article (entitled Death of the Naturalist) as being the concerns of Nature writing: joy and anxiety. Indeed, this sensibility manifests quite powerfully in the recently published Apple Anthology, a volume of poetry and prose that examines the farming and broader cultures centred around apples. In this way, this collection continues the example of Collis.

Nature writing in British literature (both fiction and non-fiction) occupies a rich seam and it runs wide and it runs deep and is currently enjoying a renaissance, exemplified in the work of Mark Cocker, Robert Macfarlane and Rob Cowen, whose recently published Common Ground explores the ‘edgeland’ between town and country.

Collis’s writing about Nature achieves what Mark Cocker described as the genre’s capacity to remind us that in Nature “We become part, not all.” This sense of the relationship is where While Following the Plough concludes, as Collis – in a state of delight, it’s fair to say – recognises the energies that suffuse the land. In the chapter entitled View of the Whole he writes “Thus the Circle, thus the Order, confined within the little space before me – type of all Nature’s vast, relentless world. And as I stood on my pile, this year, and next year, looking across the land, I looked out across centuries.”