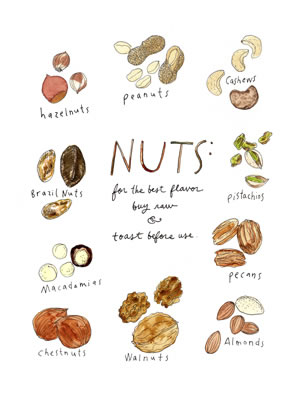

Nuts have been part of the human diet since our earliest foraging ancestors. Many people today eat a variety of nuts as part of a healthy balanced diet, but in recent years we have begun to see a shift towards a higher consumption, especially of almonds, cashews and coconuts, as we replace dairy products with nut butters and nut milks, animal protein with nuts, gluten flours with nut flours, and use nut oils.

Nuts are beneficial in supporting good heart, brain and bone health, but we need to eat them in balance, and consideration must also be given to the people and ecosystems that produce our food. California, for example, grows 80% of the world’s almonds, and the vast monoculture in the water-scarce state is creating environmental damage there.

Even though nuts are available all year round in British shops, I think of them as winter food, when markets are full of unshelled nuts. Sharing conversations while cracking open nuts is a very satisfying way of spending a winter’s evening, and it’s pretty hard to beat roasting chestnuts in front of an open fire on a cold, frosty night.

My favourite nuts are sweet chestnuts, cobnuts and walnuts. Whilst they can all be grown in Britain, most are imported, though there are some commercially grown UK walnuts and cobnuts available. You can forage for chestnuts but they tend to be rather small in comparison to the plump varieties from Italy, Spain, Portugal and France.

Chestnut

The European chestnut (Castanea sativa), also named sweet chestnut, is a tree of great longevity. Beside the parish church of Totworth in Gloucestershire is a sweet chestnut tree – though some say it’s more like a mini-woodland, as many of the branches have rooted and it’s hard to see where the original trunk ends and the new ones begin. The main trunk could be 1,100 years old, making it one of the oldest trees in the country. The Romans, who probably introduced chestnuts to Britain, ranked them alongside the olive and the grape as the plants of most importance to civilisation.

Chestnuts have a far higher carbohydrate content than other nuts. With a low content of protein and fat, they are comparable to other starch foods such as potato, plantain and cereals. Traditionally chestnuts have been grown in areas unsuitable for arable crops, to provide carbohydrate nourishment. Their distinct composition has given rise to the nickname ‘the grain that grows on trees’; in France sweet chestnut is called l’arbre à pain – ‘the tree of bread’. The high vitamin C content of chestnuts also sets them apart from other nuts.

People with grain allergies can use chestnuts and chestnut flour as substitutes, as they contain no gluten. Of course there are those with nut allergies, too, and an allergic reaction to nuts can be life-threatening. Some people who are allergic to one or more types of nut can safely tolerate others, but there are those who need to avoid all nuts. About 1 in 200 people in the UK has an allergy to a tree nut. Sweet chestnut is the least common nut allergy in the UK, with cobnut and walnut allergies being more prevalent.

Walnuts

Walnuts have long provided us with nourishment. The Ancient Greeks called walnuts karyon, or ‘head’, probably because the shell resembles the human skull and the kernel bears a resemblance to the brain. The Romans cultivated the walnut tree widely, but thought the nuts looked more like testicles and consecrated the walnut tree to Jupiter, the king of the Roman gods, calling the nut ‘gland of Jupiter’. This became condensed to juglans, giving rise to the scientific name, Juglans regia – literally, ‘royal nut of Jupiter’.

Walnuts are an excellent source of the anti-inflammatory alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), and in studies on the cardiovascular health of men the form of vitamin E found in walnuts seems to provide significant protection from heart problems.

Walnuts also contain several unique and powerful antioxidants that are available in only a few commonly eaten foods. These include juglone, tellimagrandin and morin. Antioxidants are critical to good health and are part of what determines the way we age.

Cobnuts

A cobnut is the cultivated larger form of our native wild hazel (Corylus avellana). Since ancient times hazel trees have been an important source of food and coppiced wood. In Celtic folklore hazel represents wisdom, and in Norse mythology it is known as the tree of knowledge. In Victorian Britain there were about 7,000 acres of cobnut trees, mostly in Kent. Today there are only about 400 acres.

Cobnuts are a good source of vitamin E and are high in the mono-unsaturated fat oleic acid, also needed to support a healthy heart. Cobnuts contain potent phytochemicals, including proanthocyanidins, powerful antioxidants that studies show play an important role in decreasing the risk of chronic disease, and quercetin, which can lessen allergic symptoms by stabilising mast cells and preventing them from releasing histamine.

Chestnuts, walnuts and cobnuts are all good sources of folate; cobnuts are exceptionally rich in this important nutrient. Folate is a B-complex vitamin necessary for normal cellular function and homocysteine conversion, and plays an important role in preventing foetal neurological defects. Nuts are an excellent source of minerals such as iron, calcium, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium and zinc.

Two potential problems in all nuts, seeds and grains are phytic acid and enzyme inhibitors. Phytic acid is the principal storage form of phosphorus, which needs to be degraded to be made available. In addition, phytic acid readily binds with other minerals, making them also unavailable. Whilst some people have an intestinal microbiota able to degrade phytate, thus releasing nutrients that the body needs, others do not.

The enzyme inhibitors can prevent digestive enzymes working, leading to digestive disturbances. Many traditional cultures intuitively deactivated both phytic acid and enzyme inhibitors by soaking nuts in a salt solution and drying them at a low temperature, thus increasing the bioavailability of the nutrients. If you eat a lot of shelled nuts throughout the year, it is worth considering soaking and drying them, but there is probably little need to do this to the nuts you enjoy straight from the shell over the winter months.

A few seasonal nut recipes to try:

Chestnut soup

Serves four

2 tbsp olive oil

2 medium onions, chopped

2 cloves of garlic, finely chopped

6 parsnips, peeled and chopped

500ml vegetable stock

500ml milk (traditionally cow’s milk, but oat milk works fine)

a small handful of thyme leaves, chopped

250g roast, peeled and chopped chestnuts

salt and black pepper

Gently cook the onions and garlic in the olive oil until soft. Tip in the parsnips and cook for a further 5 minutes. Add the stock, milk, thyme and chestnuts, bring to the boil and simmer for 30 minutes. Sieve or blitz with a blender, adding a little water if too thick. Return to the pan and warm through. Season as necessary with salt and pepper, ladle into four bowls and serve.

Apple and cobnut salad

Serves four

a bunch of watercress

a handful of purslane

1 small head of radicchio

4 tbsp hazelnut oil

1 tbsp apple cider vinegar

1 shallot, peeled and finely chopped

2 medium-sized eating apples

2 handfuls of green or dried cobnuts

Pick over the watercress and purslane. Separate the radicchio leaves, breaking them into smaller pieces as necessary. Make the dressing by combining the hazelnut oil, cider vinegar and shallot. Quarter and core the apples and cut into fine slices. Put into a bowl with the salad leaves and cobnuts and gently toss with the dressing. Divide between four bowls and serve.

Walnut and rocket pesto

100g walnuts

2 spring onions

2 large cloves of garlic

100g rocket

6 tbsp walnut oil

3 tbsp olive oil

½ tsp chilli pepper

salt and black pepper

Very finely chop the walnuts, spring onions, garlic and rocket. Slowly, using a wooden spoon, beat in the oils. Add the chilli pepper and season with salt and black pepper. Will keep well in the fridge for a week.

Chestnut-honey cake

4 large eggs, separated

100g runny honey

a pinch of salt

40g unsalted butter, melted

75g chestnut flour

25g ground cobnuts

½ tsp vanilla extract

Preheat the oven to 180 °C. Butter a loose-bottomed 25cm cake tin and line it with baking parchment. In a food mixer whisk the egg whites with the salt until soft peaks form. Transfer to a clean container. In the same mixing bowl whisk the honey and egg yolks together until very light, thick and creamy. Mix in the melted butter. Fold in the chestnut flour and ground cobnuts and gently fold in the egg whites. Pour the batter into the prepared tin and bake for 35–40 minutes or until an inserted skewer comes out clean. Allow the cake to cool slightly before turning it out.