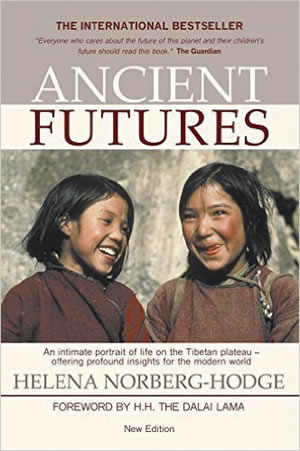

The original edition of Helena Norberg-Hodge’s Ancient Futures was published in 1991. It was by far the most detailed description, analysis and forecast of the consequences of corporate globalisation, which was just then building speed. The book’s primary focus was on the profound impact of the new global economy on the Indigenous peoples of Ladakh, a mountainous region squeezed between India, Tibet, China and Pakistan. Now an updated edition of the book brings further reporting about the growing negative impacts of globalisation and the worldwide resistance to it.

Most important about this book and its analysis, in my view, is that Norberg-Hodge does not depend on second-hand intellectual analyses, but on her own deep engagement with an exquisite local culture that was completely content in its ancient traditions of small-scale farming, family practices and local governance. “In Ladakh, I encountered a landscape that was more beautiful than anything I had ever seen,” she writes, “and a people who were happier and more peaceful than any I had ever met.”

The author first visited Ladakh in 1975, and continued to visit every year after that. Ancient Futures provides beautiful detail about what she saw and experienced there, including the accelerated destruction of a peaceful and democratic Indigenous society, increasingly forced to resist global economic pressures. Globalisation brought demands for new resources, expansive growth, new technologies, cultural homogenisation, and distant corporate control. “My experience convinced me”, Norberg-Hodge writes in a new preface, “that the central underlying problem facing humanity is that distorted economic priorities have come to overwhelm all other considerations.”

The global economy, she continues, is “a techno-economic system that commercializes every aspect of the world around us – even life itself.” She writes that “tastes and diets are homogenizing; minds are homogenizing… In the four decades since I first went to Ladakh, the conflict between the global market and local traditions has continued and intensified.” But, she says, “there is growing awareness of how much Ladakh has to offer. Self-reliance, social harmony, ecological balance, and spiritual sophistication are real, and their value is increasingly recognized.”

By the time the book first came out, Norberg-Hodge was arguing that global economic outrages needed to be resisted globally as much as locally. In the mid-1990s, she joined forces with Teddy Goldsmith, Doug Tompkins, Vandana Shiva and many other leading activists, whose efforts are described in new additions to the book. Their goal was to build an effective international movement opposing economic globalisation. The collaborations ultimately led to creation of the International Forum on Globalization, dozens of huge public teach-ins, and protests around the world, notably the massive uprising in Seattle in 1999 that closed down the World Trade Organization formation meetings.

Norberg-Hodge deserves praise and credit for this book, a revelation of a beautiful living culture, and for being among the intellectual leaders of a new movement that might finally save the day. Her awareness and actions are rooted in the time she spent every year among the Indigenous peoples of Ladakh, experiencing the glorious life they were attempting to continue. “We forget”, she writes, “that the price for never-ending economic growth and material indulgence has been spiritual and social impoverishment, and the loss of cultural vitality… In Ladakh I’ve known a people who regard peace of mind and joie de vivre as their unquestioning birthright. I have seen that community and how its close relationship to the land can enrich human life beyond all comparisons with material wealth or technical sophistication. I have learned that another way is possible.”