At a time when schools the length and breadth of the UK are struggling as a result of serious underfunding, we need to take stock and ask fundamental questions about whether they are fit for purpose. In the long run, will throwing more money at an outdated model solve anything?

In England, there have been many costly developments in education since the late 1980s – the National Curriculum, tests, league tables and, latterly, the academies and free schools programmes. Arguably, none of these was conceived with the interests of children in mind, but rather for political ends. And their effect on children and on the attitudes of young people towards education has been largely negative. Asked what they think of school, too many children say that it is boring. What an unbelievable waste of childhood. What an inexcusable waste of resources. If one aim of education is to encourage a love of learning, on this count alone the system is utterly failing many of our young.

As a society we cannot afford to turn young people off education. They are the future. The government is right in saying that our future depends heavily on the quality of our education system. But this raises the issue of what education is for, and what kind of future is envisaged. These questions are at root about what it means to be human and the role that education must play in realising our common humanity.

As a society we are all too aware of the struggle to cope with the effects of globalisation and conflict, both of which prompt serious questions about community cohesion and integration. And the challenges we face as a consequence of climate change are urgent. All these demand that we ask searching questions about the purposes of education.

Is it about enabling those living in rich countries to increase their wealth regardless of the impact on others in less developed parts of the world? Is it about providing a labour force to fuel the relentless pursuit of economic growth? If so, we are likely to see growing discontent in those countries which are exploited by the West for their natural resources or their cheap labour as they vent their anger and desperation at our profligacy.

If instead we instil in young people the values, attitudes and skills to create a fairer and more sustainable world, this can contribute to creating a society in which the inequities are gradually ironed out and in which east and west, north and south can coexist peacefully. Nothing less than this is a reasonable goal of education.

It is no longer good enough to feed young people information and knowledge that bolster the global divide. Science, history, geography, literature, economics and food technology taught without reference to ethics are barren. Instead of imparting knowledge in a vacuum, we must find ways of showing children the power of that knowledge by drawing out the connections between subjects and how they relate to the real world.

If, through their lessons, young people explore the responsibilities of farmers, drug companies, the oil industry, supermarkets and clothing manufacturers, they are more likely to leave school understanding that they too have responsibilities as members of a global community; that each one of their actions – buying clothes, eating a burger, driving a car, switching on the tumble dryer – has an effect on others in different parts of the world and involves a moral choice on their part.

If children learn to connect with these issues at school by analysing, questioning, debating and using their minds to delve beneath the surface, there is a chance of shaping a better world. There is a chance that young people will see that we can each make a positive contribution through work and the way in which we live our lives.

How can this shift in what and how children learn be implemented? How can schools incorporate this moral dimension so that children are challenged personally to think critically and to make ethical choices?

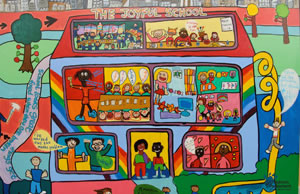

It is difficult for children to engage with global issues until they have some understanding of local issues. Their own experiences must therefore be the starting point. Two key questions are, how do members of the school community treat each other? and, how does the school community as a whole take care of the world? In answering these questions, schools must find ways to become equitable, inclusive and ethical, each one a microcosm of how we want the world to be. If these questions are addressed by schools, there is a better chance that they will be addressed by society as a whole.

To become an equitable community entails giving every child, teacher and parent a voice and ensuring that each voice is heard and every voice counts. When children are involved in decisions about their learning and assessment as well as in decisions about how their school is run, they become more engaged and motivated. When parents have the opportunity to participate in discussions and decisions about issues that are of concern to them, their children do better. And when teachers and schools have the autonomy to develop methods and approaches that are appropriate to their students, they are better able to meet the needs of local families.

Schools will only become inclusive by caring for every one of their members – adults as well as children. By focusing on the importance of relationships, by making sure that each child and child’s family are known, by giving all teachers a pastoral responsibility that is integrated with their academic role, schools can ensure that every child feels secure and supported. This is no small task, but it is only by taking relationships seriously and by valuing all members of the school community regardless of race, colour, creed, appearance, disability or sexual orientation that they will be able to say that they are truly inclusive.

To be an ethical community, schools must ensure that their ethos, curriculum, policies and practices are integrated and have a moral purpose. What this means in practice is that what children are taught and how the school operates on a day-to-day basis do not contradict each other. For example, if children learn about fair trade, the school’s purchasing policy should prioritise fair-trade goods where possible. If children are learning about the futility of war, the school bank account should not be with a bank that invests in the arms trade. If children are learning about climate change, this must go hand in hand with a school transport policy that puts bikes before cars, and an energy policy that includes insulating the school and buying energy from renewable resources. In this way, children learn that change is possible and they are part of it.

There is also emphasis on the word ‘community’ – on creating schools where all people have a sense of belonging and can actively contribute, where education is a dynamic, meaningful and relevant process that celebrates innovation and unleashes creativity, and where exciting ideas can blossom and take root. This is the challenge for schools in the 21st century, a challenge the English state system does not currently seem to be rising to. By way of contrast, the Scottish and Welsh systems are undergoing radical reform, a process that in both countries involves strengthening the teaching profession and encouraging new ideas to build the active participation of parents and children.

Looking at the wider social picture and how education fits into it, the environmental commentator George Monbiot has argued that we need to rebuild local communities in order to overcome the isolation and alienation that many people feel. The worsening mental health of the population is surely evidence of the need for deep social change. Monbiot believes that by developing a richly participatory culture we can remake society at grassroots level and that in so doing “it will eventually force parties and governments to fall into line with what people want.”

Schools are a good place to start and could be the hub of each community, a catalyst for the development of shared values based on cooperation and community regeneration. It is time to challenge the top-down, one-size-fits-all model of schooling that has been peddled by successive Westminster governments. This is not, at root, an issue about money. It is about developing a future-facing vision for education that takes account of the needs of children, of society and of the planet.

As the saying goes, it takes a village to raise a child. It is time for all of us to play our part. Our children deserve nothing less.