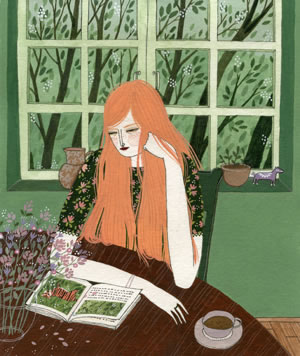

For more than a decade now, there have been strong advocates of the benefits for human wellbeing not only of slow food, but also of slow cities, slow travel, slow parenting and even slow sex. We would like to add another snail’s pace to the menu: the value of slow reading.

The Welsh writer W.H. Davies (1871–1940) lost his father, was brought up by his grandparents, got into trouble at school, never found regular work, and spent his twenties as a drifter in North America, surviving the winters by getting himself arrested and jailed. While he was trying to jump a freight train in Ontario, his foot was crushed beneath the wheels, causing his leg to be amputated below the knee. He returned to England and lived in London dosshouses and Salvation Army shelters, until, through the good offices of George Bernard Shaw, he published his bestselling Autobiography of a Super-Tramp in 1908. A few years earlier, he had met the writer Edward Thomas and, partly under his influence, he became a poet. His most famous poem, ‘Leisure’, published in 1911, might well be described as a slow manifesto:

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare? –No time to stand beneath the boughs

And stare as long as sheep or cows:No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass:No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night:No time to turn at Beauty’s glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance:No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began?A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

For Davies, modern man has relinquished his capacity to spend free time in the lap of Nature. The poem urges us not to rush, but to slow down, to stop. The words “no time” appear in each of the seven rhyming couplets. The colon at the end of each stanza creates a pause, and then the repeated question forces the reader to mark time and to make time, to see simple things that we usually ignore (a squirrel storing food for winter, the star-like glint of the sun’s reflection in water). The “stare” overcomes our constant sense of “care” and makes us care in another sense – care for our precious, beautiful, vulnerable environment.

No time to stare, no time to see, no time, no time: it’s a phrase that we all, with our busy, busy lives, can understand. Especially in a world, unimaginable to Davies, where texts, emails and messages on social media invade our headspace at every moment of the day.

Hardly a week passes in which there is not some new media report into the growing crisis of mental health among people, which seems to be linked to conflict with friends, fears about body image, and other pressures exacerbated by social media. The epidemic of self-harming among teenage girls; the millions of pounds spent by the National Health Service on stress, anxiety and related disorders; the cost of burnout to businesses, organisations and especially the NHS itself: the litany of adverse effects of the pace of modern life is depressingly familiar.

There are, of course, many ways of dealing with stress, and most of them involve the simple expedient of slowing down. Obvious examples that come to mind are a walk in the park or the country, stroking a pet, and the pleasures of gardening. But one of the oldest remedies of all is the reading of poetry. The great 18th-century reader and writer Samuel Johnson said that the only purpose of writing was to enable the reader better to enjoy life or better to endure it. He read the entire works of all the English poets, not least in order to redirect his spirits away from his own depression and physical ill health.

For centuries people have turned to poetry in dark times. John Stuart Mill claimed in his Autobiography that reading the poetry of William Wordsworth cured him after he suffered a severe nervous breakdown as a young man, and that thanks to poetry he was able to manage his depression for the rest of his life. Queen Victoria said that Tennyson’s In Memoriam was the only means other than the Bible through which she coped with the death of Prince Albert.

What is the particular quality of poetry that gives it such power? The answer surely is that, of all kinds of writing, poetry is the form that most demands slow reading.

Poetry is language in concentrated form. Poems make you feel and they make you think. They take you out of yourself, transport you to other worlds, away from your present troubles. Because they use words with beauty and care, they demand to be read with attention and without rush. The words must be savoured, because they are the linguistic equivalent of the best food and wine. Most of the time, we fill our minds with words that are the equivalent of fast food. Poetry is slow mind food, real nutrition for the soul. Attentive reading slows the breath and empties the mind of other cares. The rhythms of a good poem may be inherently calming and therapeutic, regardless of the subject matter. The brevity of a poem can be a blessing for many people who, when stressed or depressed, lack concentration and sometimes are unable to read. The subject matter of poetry – memory, love, the restorative power of Nature, confrontation with sorrow and death – often serves for attentive readers as a mirror of their own feelings, a welcome discovery that we are not alone.

Slow reading encourages us to stop. “Compose yourself” is a phrase that we might say to ourselves when we are stressed or flustered. The word ‘compose’ here comes from the Latin meaning of ‘putting things together’ – that is to say, creating order. The chime of rhyme, the reassurance of repetition, the sense of balance in the pattern of a stanza or the fourteen lines of a sonnet: all of these are formal devices that poets use to bring order to the chaos of experience, and a sense of musical harmony, of resolution.

Poets, like those who write music, are composers. They take emotions and ideas and put them into harmonious, melodious order. There is no better example of this process than that special form of poetry known as the sonnet: fourteen lines, a regular five-beat rhythm, a pattern of rhymes, and sometimes a twist in the tail.

In his sonnet ‘Bright Field’, R.S. Thomas urges us to remember that life should not be rushed, that hurrying is an illusory quest for a “receding future”: instead, like W.H. Davies, we must make time for “turning aside”. Similarly, one of Wordsworth’s most composed poems is that celebration of a moment of stillness at dawn before the start of a busy London day – ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge’:

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

Poetic moments such as this are typically characterised by solitariness. W.H. Davies, R.S. Thomas and Wordsworth connect in stillness with Nature because they are alone. But, for us as readers, there is a sense that we are not alone: by slowly reading their words, reanimating their vision in our imagination, we feel connected to their world and thus to our world. The slow poem performs two sorts of work at the same time – an easing of pressure is combined with a sense of community: “Others have felt the same as me. Ah, that’s it – that’s exactly how I feel.”

John Keats beautifully articulated two “axioms” for poetry in a letter to his publisher, John Taylor:

1st. I think poetry should surprise by a fine excess, and not by singularity. It should strike the reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a remembrance.

2nd. Its touches of beauty should never be half-way, thereby making the reader breathless instead of content. The rise, the progress, the setting of imagery should, like the sun, come natural to him, shine over him, and set soberly, although in magnificence, leaving him in the luxury of twilight.

A spiritual luxury, that is – not the relentless quest for material luxury that Wordsworth condemned when he spoke in another sonnet (‘The World Is Too Much With Us’) of how, “Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.”

It was our belief in these ideas that led us to establish ReLit, a charitable foundation devoted to the proposition that slow reading of nutritious literature, especially in the compacted form of poetry, may work as a form of stress relief and combating loneliness. Reading is cheap and, in contrast to pharmaceuticals, has no deleterious side effects. Whether by the bedside of the insomniac, in a hospice or in the anxious environment of a doctor’s waiting room, there is nothing to lose and everything to gain by having a volume of poetry to hand.

That was the motivation behind our publication in 2016 of the anthology Stressed Unstressed: Classic Poems to Ease the Mind and now The Shepherd’s Hut, a collection of original poems and free translations of lyrics from several different poetic traditions. Among the new poems is one that tries very simply to catch the spirit of slow reading, by asking the reader to stop and make time for words, for images, and even for the pause that comes at the end of a line of verse and the stress-free white space that surrounds the thoughts:

SLOW READING

Take time for each word,

Give room to white space,

Listen for the beat,

Tune to the weather,

Rekindle memory,

Life-scape and heart-leap.

Know that poetry

Is not of the world:

It is in the worth

Of the words to you,

Patient reader, open

To the spirit of slow.