OVER THE PAST year, much attention has been focused on encouraging the governments of the G8 nations to 'Make Poverty History' by ensuring fairer trade, increasing aid and cancelling debt. While the aims are clearly laudable, insufficient attention is being given to what form the aid should take and what model of economic and agricultural development countries in Africa should pursue.

A fairer and more equal distribution of resources will not be enough if we do not fundamentally rethink the way we farm, in richer and poorer countries alike. The culture that has given us industrial agriculture is changing climate globally and destabilising even the little that remains of the biosphere's natural ecosystems. If this trend is not checked, the likelihood of the re-emergence of sustainable agriculture that can continuously feed the world will be drastically reduced.

The Kyoto Protocol is a timid attempt to reduce the impact of climate change. But even that attempt has been rejected by the United States of America, the country that causes a quarter of the total magnitude of climate change. What chance has life got of continuing as we now know it? Very little.

Assuming that we can curb climate change, we can solve the problem of achieving sustainable food production only by adopting agricultural systems that can maximise the biomass that we require, while at the same time strengthening the homeostasis of the agricultural ecosystem. Will organic farming do this for us?

The answer is 'Yes', but only if we take it seriously and do all the necessary research and development to bolster rather than bypass the natural cycles that improve the functioning of the ecosystem as a whole, including those parts of it that are not cultivated.

CAN THIS BE done? Why not? Previous farming communities have been doing it for thousands of years. With our increased knowledge, we should do even better.

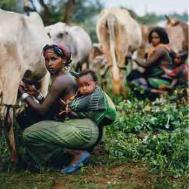

Some farming communities in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, have started to practise sustainable organic agriculture and are obtaining reassuring results. These communities started working on severely degraded land. They carried out physical soil-erosion control activities (terraces, check-dams across gullies, and trench bunds). They restricted free-range grazing to small areas, and cut and carried grass and other leaves to feed their animals. Trees and grass cover then returned fully to the land. This was all traditional practice to them, but the breakdown of their local community organisations had prevented them from acting collectively to use this knowledge. Encouraged to revive their community organisations, they agreed a set of bylaws to enable them to do that. These organisations were then trained in how to prepare and use compost, and latterly, in transplanting their long-season crops (finger millet, sorghum, maize) to ensure a long enough growing season even when the rainy season becomes short. And the rainy seasons are getting shorter and more erratic owing to climate change.

Unfortunately, research in the last five or so decades has focused overwhelmingly on selecting varieties that maximise yields under irrigation and chemical fertilisers. If a commensurate amount of research were conducted on selecting varieties that maximise yields under increasing soil fertility from organic management, I have no doubt that the results would be comparable. But of course, in contrast to those of industrial agriculture, they would be sustainable.

Organic farming, I am sure, will feed the world. I am also sure that unless organic farming re-expands, the human component of the world will eventually shrink. And if climate change is not curbed, there will be no biosphere as we now know it, let alone food as we now have it. o

This article is an extract from a speech given to The Soil Association.

Tewolde B. G. Egziabher is Director General of the Environmental Protection Authority of Ethiopia, and co-founder of the Institute of Sustainable Development.