I’ve been thinking about something Richard Layard, a leading scholar at the London School of Economics, said recently. An essential feature of school life, he argued, should be to teach our students to care for other people – to become compassionate and attentive young adults who will make our world a better place.

I couldn’t agree more. Watching my own university students grow into happy, fulfilled women and men who feel a responsibility to their communities has been one of the greatest joys of my teaching experience.

Yet if that is our mission, are we as university administrators and academics doing all we can to support it? If that is what we value, are we focusing campus resources in the most beneficial, student-centred way? Becoming a whole person is in part a function of the intellectual enrichment at which universities excel. But it is not enough to celebrate the life of the mind when students’ minds are overburdened by stress.

Numerous indicators show we have a crisis on our hands. In 2015, the London-based Institute for Public Policy Research found that the number of first-year university students reporting a mental health condition had increased since 2006 by nearly 500%. In that same time period, suicide deaths among students rose by 79%.

I’ve seen the way the alarm is being sounded, both at my university in Canada and across the UK. Students, faculty and administrators alike have organised, advocated and invested in critical services to promote student wellbeing and respond to crises when they occur. According to one administrator at the University of Bristol, mental health is at the top of the agenda of vice-chancellors across the country. Yet for all we’re doing, the data shows we still have far to go. Our universities are about to open their doors to a new class of bright young people. We owe it to them to create a campus system that addresses their mental health needs.

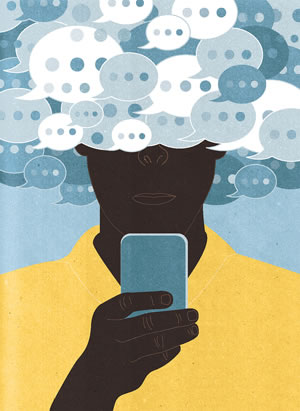

Many factors exacerbate mental health issues on campus – pressure to succeed, financial strain, the existential confusion of young adulthood, and more – but one place to start may be resting in the palm of our hands.

The American psychologist Jean Twenge of San Diego State University in California wrote in The Atlantic magazine last September, “The twin rise of the smartphone and social media has caused an earthquake of a magnitude we’ve not seen in a very long time, if ever.”

Twenge’s work is part of a growing body of research that finds screen time less fulfilling and more anxiety-inducing than good old-fashioned face-to-face time. That’s a problem for young people in the UK, who have been estimated to spend almost four hours a day on their phones.

What’s worse, research suggests that, developmentally, young people are especially susceptible to the isolating effects of smartphones and social media. Earlier this year, an article published in Nature pointed out that adolescence is a time when peer acceptance becomes paramount, meaning that not only are young people more likely to follow their friends onto social media platforms, but they’re also more sensitive to the feedback they receive on those platforms.

The cycle is vicious. According to researchers at the University of Sheffield, “spending an hour a day chatting on social networks reduces the probability of being completely satisfied with life overall by approximately 14 percentage points” for 10–15-year-old children. Statistically, that’s more significant than the comparable effects of skipping school or being raised in a single-parent household.

Young people are well aware of the effects of smartphones and social media on how they feel. A 2017 Royal Society for Public Health study on the issue in the UK found that “young people themselves say four of the five most used social media platforms [Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook and Twitter] actually make their feelings of anxiety worse.”

And they’re taking action. A recent survey by the research group Origin found that 34% of people between the ages of 18 and 24 have deleted one or more of their social media platforms, in part because of the negativity they experienced.

These young people want an overhaul of their relationship to technology – and universities can be allies in helping students to unplug and reconnect. Fortunately, students, faculty and administrators have already put forward solutions we could implement right away. The academic Donna Freitas surveyed more than 1,000 college students about social media. In a School Library Journal article summarising her findings, Freitas wrote:

Over and over, at every university, I heard stories like this: “There’s this one spot in the third-floor sub-basement of the library? By the wall past the elevators? I always go there to study, because the Wi-Fi doesn’t reach. You have to get there early – it’s always jammed.”

Following their lead, Freitas recommends wifi-free zones on campus, where students can give unmitigated attention and care to friends, check in with their own thoughts, and reconnect with Nature.

Similarly, in their essay ‘Elevating the Student Experience’, Amy Aponte, an expert on campus infrastructure, and Gay Perez, executive director of housing and residence life at the University of Virginia, have called for “deep attention spaces” – device-free dining halls and dorm rooms, optimised with natural light and tranquil aesthetics. More provocatively, they suggest that tech-friendly spaces “be made intentionally less desirable to inhabit for longer visits”.

Inside the classroom, professors must do their part to help students engage, not only with the material, but also with the community around them. Technology may be an aid in the modern classroom, but the work of building meaningful relationships requires a human touch. This isn’t supplemental to our work as educators: it’s integral. The best learning happens in caring classrooms where people feel secure, respected, valued and seen. And in my experience, a deliberate effort to foster interaction between professor and student, and among students as peers, enriches the classroom experience in all directions, making it more rewarding to teach as well as learn.

Of course, systemic change on a critical issue like mental health requires concerted leadership from the top. In addition to investing in traditional mental health services and exploring student-centred approaches like the ideas described above, school administrations should commit to tracking the determinants of their students’ wellbeing.

To paraphrase a refrain from Layard, if you treasure it, measure it. Consistent, reliable data will help us assess, adjust and improve our efforts to make universities places where students can be happy, healthy and whole.