‘Parish’ is a bond-word: a covenant with place. Deeply rooted within western culture, it expresses our need for a footing in the world, for local attachment.

Consequently, the parish idea is not only highly potent – binding secular to sacred, human community to natural landscape – but also problematic and politicised, encapsulating many of the tensions contained in our longing to belong. Evoking an idyll of (usually rural) settlement, the extended form ‘parochial’ is almost always employed in the derogatory sense of blinkered insularity: the social drawbridge slammed shut. For those watching in dismay at the growth of popular national movements across Europe, the new parochialism is a doubly bad thing, denoting both fear of the outsider and the retrogressive urge to regain some Edenic past.

Yet, according to the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh, “All great civilisations are based on parochialism – Greek, Israelite, English...” Continuing, “it requires a great deal of courage to be parochial,” Kavanagh’s point is that parochialism involves confidence and pride in the authenticity of local experience, which requires no constant comparison with or recourse to neighbouring forms of expression. Parish is, after all, the nearby community, and this ‘nearness’ is the key to most of the perceived blights and benefits of parochial life – its equal suggestion of settled support and suffocating pettiness.

That the word ‘parish’ has such a painful double edge is due to its unusual blend of associations. In ancient Graeco-Roman society, its original form paroikia described the community of people either living physically beyond city boundaries (literally ‘those beside the house’) or as non-citizens within the walls – those who lived nearby, but didn’t quite belong. It is ironic that ‘parochial’ has come to epitomise insularity and self-containment, when its original meaning is far closer to our contemporary definitions of ‘stranger’ or ‘refugee’. Its effective transition in meaning, from ‘outsiders’ to ‘insider’, came about when the early Christian Church adopted ‘parish’ as a description of its own local organisation. The Christian paroikia were those who didn’t belong in a worldly sense, but had found a new kind of ideal home, a heavenly destination.

When, in the late 6th century, Roman Christianity returned to Britain with the arrival of Augustine on the Kent coast, this parochial idea came ashore too. Gradually the parish grew into an essential building block of neighbourhood, its ‘vestry’ of local officers the nucleus of local government. Only in my grandparents’ lifetime did the parish finally concede to secular authorities this historic responsibility – not for souls, but for schools, roads, poor relief and myriad other details of communal life. According to the vast leather-bound minute book in the vestry safe of my own church, parish meetings until the early 20th century appear mainly to have revolved around such matters as the appointment of local constables and concerns over local drainage. The parish was a place both hallowed and grounded.

This jurisdiction could, of course, be bleak and oppressive – think “God is love” emblazoned above Oliver Twist’s workhouse – and so it is unsurprising that parochialism emerged as a curiously ambivalent concept: both a communal ideal to aspire to, and an utterly stifling place from which one must at all costs break out.

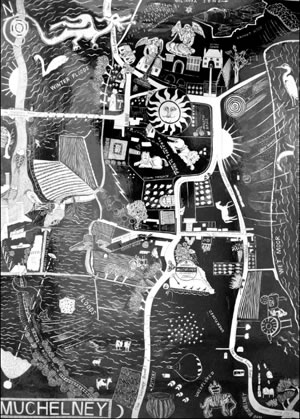

The power of parish as a concept has long been recognised in the pioneering work of Common Ground, the environmental charity founded in the early 1980s by Roger Deakin, Sue Clifford and Angela King. Reviewing their long-running Parish Maps project, which encouraged local groups to create imaginative depictions of their neighbourhood, Clifford explained that ‘parish’ was chosen because it offered an equivalent to the German Heimat – a way of describing “the intersection of culture and nature” and “deeply felt ties of familiarity, identification and belonging”. ‘Parish’ thus became an imaginative bridge between concrete local communities and the less tangible, psychological responses through which we intuitively seek out a place of personal settlement and wellbeing.

In a fascinating introduction to Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne, Richard Mabey considers that White’s parochial focus – a single window into the world – lies behind the enduring influence and appeal of his work. As Mabey puts it,

‘Parish’ is a very laden concept. It has to do not just with geography and ecclesiastical administration, but with history and a system of loyalties. For most of us, it is the indefinable territory to which we feel we belong, which we have the measure of. Its boundaries are more the limits of our intimate allegiances than lines on a map. These allegiances have always embraced wild life as well as human...

Mabey coins the term ‘parochial ecology’ to capture White’s settled attention to Selborne, which, in turn, became a guiding theme for Mabey’s own trailblazing environmental work. “The idea of parish”, he asserted, in The Common Ground, “must underlie ... a conservation policy which takes account of human feelings.” Highlighting another priest-naturalist, John Stevens Henslow, rector of Hitcham, Suffolk (who tutored Charles Darwin and encouraged his voyage on the Beagle), Mabey comments how “it was in his parish that his most important work was done ... he was not just Hitcham’s rector but its curator.” The resonance here with the pastoral ‘cure’ retained still by Anglican clergy is plain – that truly parochial life is pastoral on both counts, formed by an ecology of care for a particular place, its people and their relation to the land.

The rejuvenation of ‘parish’ as an environmental concept in the last 30 years thus makes a clear, if contentious, case for the desirability of settlement over dispersion and mobility. Against the dislocating tendencies of global capitalism, time, tradition and terrain are valued as key ingredients in the formation of community and in the accompanying charitable commitment to one’s neighbour. Arguably, then, the parochial approach reverses the familiar dictum “Think globally, act locally”, by stressing the priority of local attention as the seed from which any authentically global worldview must grow. In unsettled times, we urgently require hopeful models of society that can be resilient without being defensive – ‘little’ without being narrow. The original community for outsiders, the parish could be just the place.