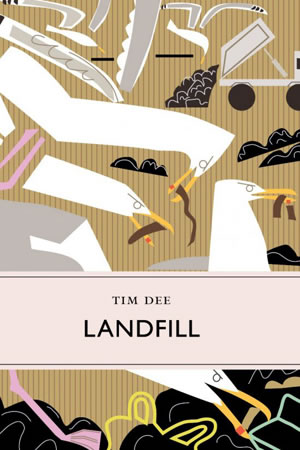

What is it about gulls? Why do they seem to be everywhere – tearing open rubbish bags, stealing chips at the seaside, flocking after tractors ploughing fields? Why are they where we are, and not where (we think) they ought to be – on the cliffs and out at sea? What was it that drew prime minister David Cameron to call for a “Big Conversation” about this issue? Tim Dee writes: “This book tells this story: how, over the past one hundred years, gulls have made their way among us in a man-made world and how, more recently, various people have met them there.” This is not so much a natural history book – although it contains lots of facts and information – for Dee’s real interest is in “exploring what these facts of gull-life and gulling-life have done to our minds”.

It seems that until well into the 20th century, gulls – never call them seagulls! – did not frequent our big cities. It is relatively recently that they have learnt to nest and breed on urban roofs. Dee’s first chapter recounts his exploration of gulls in Bristol, visiting schools, office blocks and industrial estates with a local expert who knows one 28-year-old lesser black-backed gull by sight and tells him at one garbage utility that “gulls can get a day’s food in seconds”. What is remarkable is that these big birds are habitually so close to us, closer than any other largish wild animal, almost “too big for the world they have entered”. Many urban humans see them as a nuisance, a pest, with “a resurgent rivalrous antagonism that almost any other creature of Earth can trigger in our species – that dark loathing we can find in ourselves for any living life”. But others find them fascinating.

Dee tells us of his visits to rubbish tips and reservoirs with gulling enthusiasts. Across the country there are individuals and groups who study them in detail, drawing on information about species and subspecies derived from recent DNA analysis and checking this against field observation – like the birders at the Pitsea tip on the Thames Estuary who regularly net and ring the birds to keep track of their movements. These ‘gullers’ know the subtle differences between species and subspecies, identifying visitors from the Arctic, from Russia, even from the Pacific. We are learning a lot about biodiversity, speciation and migration from this collaboration between enthusiasts and scientists: evolution is not just in the past, but continues today as birds breed across species, learn and adapt to new habitats and are influenced in turn by those habitats.

Pursuing his interest in the relation between gulls and humans, Dee studies the literature of gulls – history, novels, films, philosophy – from Henry Mayhew’s history of 19th-century London through Jonathan Livingston Seagull to Chekhov and Beckett. I found these chapters less engaging: I didn’t find a summary of The Seagull or The Birds illuminated much for me; ‘explaining’ Beckett is next to impossible. I suspect this is a matter of taste and style; other readers may well enjoy these literary excursions more than I did.

What I did particularly enjoy, late in the book, is an account of a visit to Madagascar with two scientific ecologists to study an unidentified bird call. The chapter picks up and develops a key theme of the book – the importance of attention and careful watching. Dee is left alone in a clearing in the dark of the forest night, just waiting in the silence. Time and self slip: “we – the clearing and I – entered some other realm.” Almost like a ghost, “in this blank my seeing grew. I was next to nothing and was looking at a place that was regardless of me.” With an apposite phrase – “the emptying of everything without the removal of anything” – he draws the reader into an experience I have elsewhere called a ‘moment of grace’, when the Cartesian split between subject and object dissolves. Accounts of such moments are, I believe, deeply significant in shifting our habitual sense of placing ‘Nature’ ‘out there’.

This is a book that weaves many themes: gulls in relation to human hatred and enthusiasm; diversity, speciation, evolution; human artfulness and sense-making. It may best be seen as a collection of essays around these themes, to be picked up and savoured chapter by chapter over time. Dee is trying to discover how our thinking about these birds has shaped the way we know them; and many would argue that any chance of human survival with dignity rests on developing new ways of thinking about the more-than-human world. More immediately, he certainly made me think differently about urban gulls, and so too about the badgers who dig up my lawn, and the squirrels who strip my apple trees.