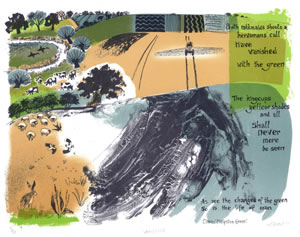

Living on the edge of Dartmoor is a joy. I can run along snaking lanes and be on windswept moorland in half an hour, watching the whole of south Devon unfold far below between misty green horizons. As I grind my way up the flanks of England’s largest granite outcrop, I’m immersed in that network of small fields, pastures and tree-studded hedgerows that is so quintessentially Devon.

There is much that is great about our farmed landscape. But this is no Wind in the Willows ideal. The fields are largely devoid of livestock, insects and birds. Their striking emerald green reflects a monoculture of highly competitive grasses, growing hell-for-leather on a super-rich diet of artificial fertiliser. A closer look reveals all too many signs of hedge-lines that once were, wetlands drained and rough moorland converted to closely cropped pasture. And then there are the huge brown expanses of dead vegetation recently sprayed with Roundup. We have sacrificed variety and vibrancy for tidiness, uniformity and productivity.

Since 1970 we have lost half of our wildlife; 1,200 UK species are extinct or under threat of it. Devon has the country’s best network of hedges, but only 38% of its 53,000km are in good condition. UK farmland loses 2.2 million tonnes of topsoil annually, and the stripping of slurry and agrochemicals by heavy rain is one of the biggest reasons why fewer than 20% of our rivers are in good health. Something badly needs to change if we want to leave future generations with a natural environment worthy of the name.

It would be wrong to blame farming for all of this, of course, and many farmers are among the best champions for wildlife. But agriculture covers three-quarters of our landscape, and intensive farming, which has the largest environmental impact, grew by 26% between 2011 and 2017.

Since the early 1970s, farming has become inseparable from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The CAP is a strange beast, stretched and contorted into a bizarre shape by politics and vested interests battling with fairness and common sense. A small amount has been directed to agri-environment schemes, but nearly 90% is simply handed out according to how much land a farmer owns. Nothing to do with food production, Nature or efficiency. It has propped up land prices, funded wholly unsustainable practices, and ensured the richest get the lion’s share. We need something a whole lot better.

By the time you read this we might have left the European Union and be moving towards a post-CAP era. So let’s imagine this brave new world. In New Zealand, where farm subsidies ended in the 1970s, the landscape is one of extremes: areas of stunning wilderness on the one hand, and miles of intensively farmed prairie on the other. It’s quite possible to see how this could happen in the UK. Most small and upland farms are kept afloat by subsidies. Without them many would go to the wall, and the market value of their land would plummet. Some areas might revert to Nature; others might be bought up by hobby farmers or put to non-agricultural uses. But in an era where the cost of borrowing money is cheap and land is a safe long-term investment, it’s all too easy to see how the larger operators could quickly buy up cheap land and intensify production, capitalising on economies of scale.

If the direction signalled by the recent Agriculture Bill is anything to go by, such an extreme situation is thankfully unlikely. Much has been said about public money for public goods, with the environment receiving special mention. But we know nothing about the detail or how much money will be available. Just meeting our existing environmental commitments requires government spending five times what it currently does on agri-environment schemes.

So what might a new and more enlightened farming policy look like? We need minimum standards that all farms must meet. As well as safety and animal welfare, this should include phasing out damaging pesticides, and reducing ploughing and slurry spreading, avoiding it altogether on steep slopes. All farms should move to a net carbon-neutral position.

We need farming to diversify and innovate. Agroforestry can be more profitable, productive and Nature-friendly than traditional farming, but it is seldom seen in the UK, as it’s not well suited to current policy. And, like it or not, new technology such as hydroponic systems might prove to be a much more sustainable and less land-hungry way of producing our food.

And we need farming to make room for Nature. This means hedges being allowed to grow out, wider field margins, and natural vegetation strips along river corridors. But we also need spaces for Nature to expand, on steeper slopes and in marginal areas around our uplands. And 3% of farmland should be managed for pollinators. In some areas, we should allow farming to withdraw altogether or reduce to much more extensive systems, so that Nature can return.

So how do we make this happen? First, we need a solid bedrock of firm regulation, banning the use of damaging chemicals for example. This could be a challenge in the current low-regulation culture.

Secondly, we need a green subsidy system that pays for things the market won’t – Nature, flood control, soil protection. It should be simple, flexible, widely available and properly funded. £3 billion a year would help restore the natural systems that sustain us. That’s a big sum, but it’s still only 0.5% of total public expenditure and compares with £37 billion for defence.

Finally, we need to be brave enough to say what type of farming is suitable where, rather than leaving the market to dictate. We need a vision for Nature’s recovery – a Nature recovery network – that farming helps deliver, not a complex set of poorly funded mechanisms that struggle to find room for wildlife around the margins.

Is this possible? I think it is, and I believe farmers would benefit just as much as the rest of us.