Growth – economic growth – will increasingly dominate our conversations. The world is on the precipice of a historic recession. Brexit was advocated, and will be judged, in terms of its impact on growth in the UK. The threat posed by exponential growth on a finite planet is now well understood.

But what is economic growth, is it necessary, and is there an alternative? These are the questions that we will need to address in the years ahead. Growth sounds entirely positive, and natural. The joy of Nature is its fecundity, its variety. To see an individual – a person, a caterpillar – grow is one of life’s pleasures.

Economic growth promises to solve one of the great conflicts of capitalism: investors can get a return on their cash, and the rest of us can enjoy improvements to our everyday lives. There is no longer a need to fight over the pie, because each year the pie gets bigger. But the reality is much more complex, and much more threatening. The belief that growth is entirely necessary is itself a driver of climate breakdown.

There is one cohort of people who indisputably need growth: investors. All investors want a return on investment. This is the reason they risk staking their money on business ventures. This return often takes the form of interest: we accept the need for interest when we take out mortgages and credit cards.

The interest on an investment is compounded, which means that it grows at an exponential rate. A simple example: an investor advances £100 in year one. She expects interest of 10% – a return of £10. The second year, the same investor puts forward that total of £110, and at the same rate expects a return of £11. After nine years she has doubled her original investment. Great news for her.

The problem arises because each investment, in order to return interest, needs to stimulate economic activity. We now know that we have not been able to decouple economic activity from environmental impacts. This means that after 10 years the environmental impact of our investor has also doubled – this could be in the form of carbon emissions, deforestation, or the use of pesticides.

And the problem becomes global in scope, because instead of a single investor with £100 we have trillions of dollars spilling around the world in pursuit of profits. This money knows no borders, so governments and corporations are trapped in a global competition to offer investors the best return. This is a race to the bottom, with the environment and human health sacrificed.

So do the rest of us need economic growth? Margaret Thatcher argued that There Is No Alternative, and TINA retains much of her influence. However, there is a growing appreciation that growth itself is not only unnecessary for us, but also extremely dangerous. Growth is a cancer.

This argument is – ironically – being validated by capitalism itself. The threat of global recession has meant that money is pouring into investments with below-zero interest rates. In some countries you can get a mortgage where the bank pays you to take out the loan. Investors are happy to lose some money – as long as it is guaranteed that they will not lose even more money.

The state can also be an actor in the economy that does not demand interest. It can borrow at extremely cheap rates – perhaps even for free – on the international markets and then advance that cash to local community groups at zero interest. There is no profit, but plenty to be gained, as voters experience improved lives – including jobs.

We can redistribute. We can tax the extremely rich and then give that money to those who need it most. This could be paid to everyone as Universal Basic Income – in the past it has taken the form of Working Families Tax Credit. The taxes can also pay for education, schools, hospitals. Investors can then focus on attempting to scoop all this cash up again through the sale of goods and services.

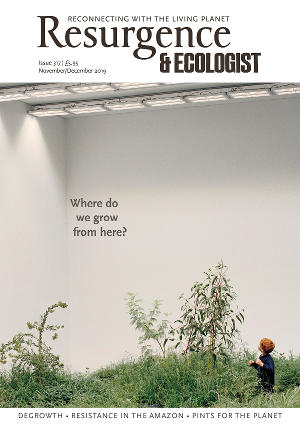

There is also the option of degrowth. This is about deliberately deflating, or shrinking, the global economy, reducing the amount of economic activity. The essentials – food, shelter, health services – could be improved and expanded, but we would produce fewer cars and iPhones. Can we be happier with less economic activity? Imagine a three-day working week without a loss of pay.

The question comes down to this: should we be focusing our societies on real wealth – free time, connection, creative expression – rather than the artificial ‘needs’ such as mouthwash and smart watches created by the advertising industry to keep the production–consumption whirligig turning to satisfy billionaire investors?

The answer to this is one of economics. But clearly it is also philosophical and political. Such a transition would involve huge change on an international scale for individuals, communities and societies. Even if such change is desirable, is it possible? And who will the agents of such change be?

These issues are explored in the Degrowth feature articles in the November/December issue of Resurgence & Ecologist.