The night before my meeting with Poet Laureate Simon Armitage at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, I have a curious dream. In it I am trying to write a poem that begins with the letter A, but there is a problem: the letters are individually as big as a house, and to get them into place appears to be some sort of monumental effort involving ropes and a lot of dragging. Just as the giant A is about to slide into position, I begin to have doubts about the arrangement. It feels somehow too obvious to start a poem with the letter A. I wake up full of doubt about my ability to write.

I decide to share the dream with Armitage, hoping he might make some sense of it.

“It means you have alphabet anxiety, and you should see a psychologist straight away,” he says to me as he picks at his fruit scone in the park’s upstairs café. “It’s not something I can help you with, obviously.”

After my diagnosis, I confess that I’m not sure where to start the interview, but perhaps we should begin with the new poetry prize and why we are sitting in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. But Armitage is more interested in not knowing where to start. “Let’s just take the conversation bus back a couple of stops,” he says, and suggests that my dream is common to the way many people feel about poetry, as something difficult and complicated.

“I think it sometimes goes back to experiences in school when poems were presented as riddles, or things that didn’t have exact answers. That’s particularly the case in the contemporary education system in the modern world, where we feel as if everything must be reducible to a solution. I think poems are a bit more open-ended than that.”

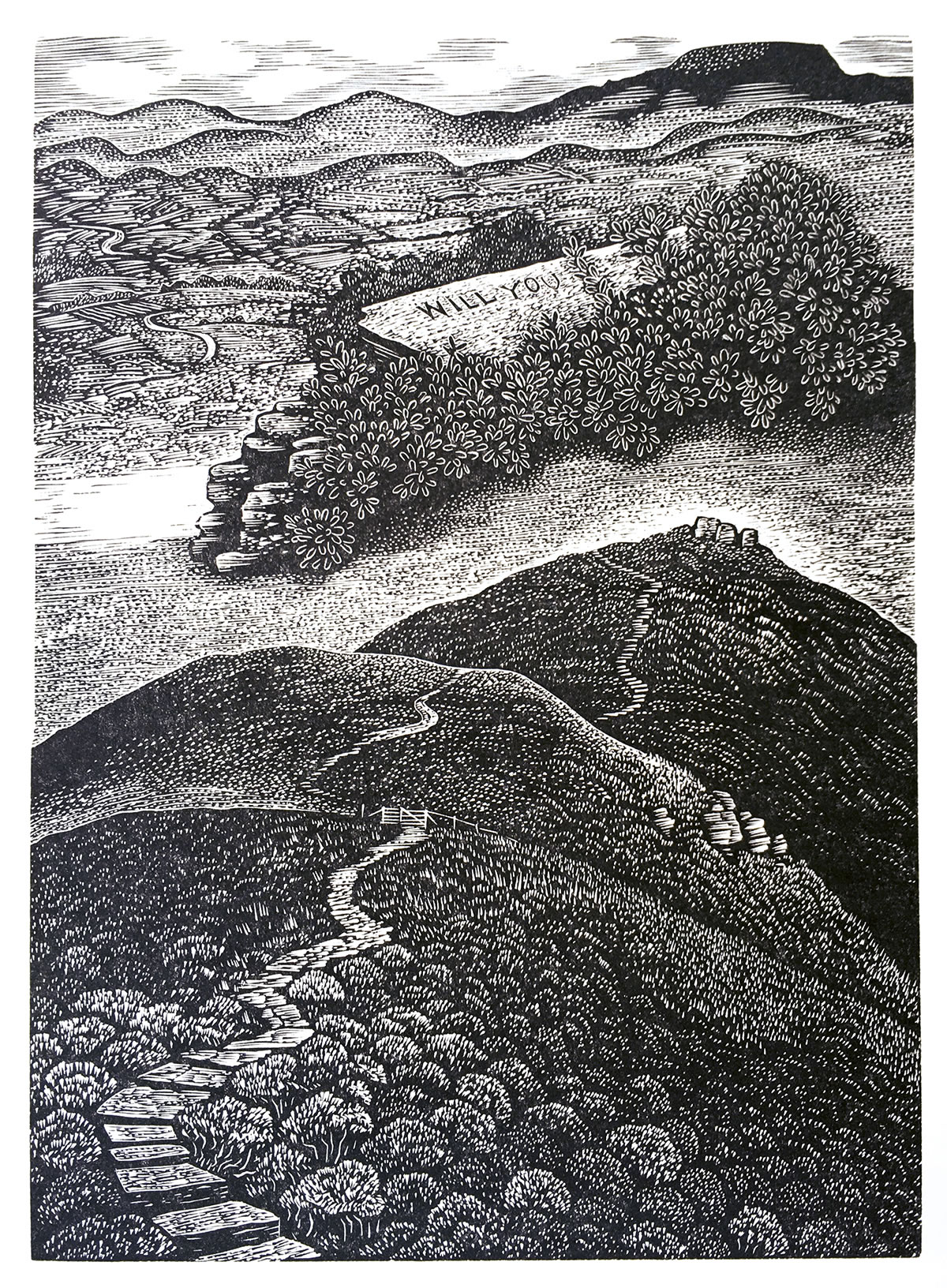

Having taken a lot of inspiration from the landscape over the years for his poetry, he is now giving poetry back to the landscape. His poems have been carved onto six rocky outcrops along the South Pennine Watershed, and walkers can hear recordings of his poetry in certain locations in Northumberland National Park using GPS technology on their mobile phones. These recent projects came, he says, from ideas developed in his various residencies at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. That’s why it seemed a natural location for his new Laurel Prize, co-organised with the Poetry School.

“It’s a place that cares about the land, about landscape. It’s full of guardians of the landscape and artists who work in it, and with it.”

The prize is part-funded by Armitage’s annual Laureate Honorarium. Each year over the next ten years, a first prize of £5,000, a second of £2,000 and a third of £1,000 will be awarded to collections of Nature or environmental poetry that highlight or raise awareness of the climate crisis. Armitage is keen for poetry to keep up with the resurgence of similarly directed writing in non-fiction. He cites authors like Robert Macfarlane, Tim Dee and Kathleen Jamie, and is certain that something alike has been taking place in poetry, but just in a “more quietly and less celebrated” manner. The prize will acknowledge the good work done in that area, and encourage more of it as well.

In other interviews Armitage has said that poetry is a fundamentally dissident art, in its form and structure, and also a subtle art in how it approaches subjects. I ask him what a medium with these qualities can do when it faces something as huge as the climate crisis, which demands such stark and immediate reactions.

“My feeling is that poetry that tries to protest and campaign often doesn’t get very far, because it becomes a little bit of a blunt instrument. People do, I think, look for subtlety in poetry. It’s one of the markers of talent amongst writers.” After a sip of tea, and a pause in which to think, he continues.

“Poetry is not a front-line art form. It’s not rock and roll. It’s not a Hollywood film. It’s not Broadway theatre. But it’s proved itself to be pretty much unkillable for thousands of years. So it’s one of our most original art forms. And as long as there’s been civilisation or even a human presence, there’s been poetry of some type.”

Perhaps the poems carved into those rocky outcrops on the South Pennine Watershed will one day become hieroglyphs that future visitors will try to decipher, he muses. But then again, I wonder, they might be destroyed sooner than that, if our current ‘progress’ continues. It makes me wonder how that relationship of poetry and landscape began for Armitage.

“If I look back to first reading Seamus Heaney and Ted Hughes when I was at school, the fact that they were writing about animals and the natural world in a really beguiling way beguiled me as well, and made me curious and interested. I wanted to have this sort of engagement with things that were different than ourselves.”

Armitage grew up in the shadow of Ted Hughes. He cites him as the first poet to open his eyes, not just to poetry and landscape, but geographically as well. Hughes grew up in Mytholmroyd, just outside Hebden Bridge in the Calder Valley, and Armitage in the Colne Valley, the next valley system south. If Hughes could write poetry growing up in a small terraced house, why couldn’t he?

“I certainly understood the things that he was talking about and the language that he was using to describe them in terms of growing up in a small, post-industrial community within a moorland setting – they were shared experiences. We tried to make sense of what it was to have one foot on the moor and one foot on the pavement.”

As Armitage speaks about Hughes, the words he uses are rich and exact, and pleasantly surprising. In his conversational language you experience the tools he uses to create his poetry. I would have loved to see him and Hughes talking together, as they once did on a trip out to the river in Devon where Hughes lived and fished. Armitage recalls this in a programme he made for BBC Radio 4 called Ted Hughes: Eco Warrior, in which he explored the side of Hughes people know less about.

“I went down to that river with him once and he was talking about how healthy and vibrant and lively that river system used to be, and then I remember this pause, and then he just said something like: ‘It’s dead now.’ I remember thinking that day that that was a very pessimistic moment. And I have been incredibly pessimistic about the prospect for us... But I’m slightly more hopeful over the last couple of years, just in the sense that so many people have come on board and the whole topic has moved from a marginal concern to something that seems to be front and centre of a lot of people’s lives and their conversations, and hopefully their actions.”

Since he became poet laureate, Armitage has been trying to tap into some of that current positivism. I wonder if the laureate has given him more of a voice, as it gave Ted Hughes, which will be heard with greater attention and to campaign with.

“Yeah, I do. I mean, I think this prize is a way of trying to strengthen that voice and give opportunity to other people’s voices. I’m not kidding myself, you know. I’m not suddenly the environment minister. But it gives me more of an opportunity than I had 12 months ago.”

As laureate, Armitage has been commissioned to write poems for various national moments. One he is particularly pleased with was written to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act, which had paved the way for the creation of the UK’s 46 Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

When he wrote the poem ‘Fugitives’, Armitage tells me, he was thinking about the idea of people finding safe spaces, making towards ground and land that still held all the mysteries and values they wanted to honour. He gestures towards the park: “A place like this, actually, this is a very kind of… defended space.” His poems are often written as a way of ritualising events and objects, and he sees poetry as dealing with things in a careful way, which the world tends not to, believing that we currently have a very crass relationship with material goods.

“If a poet talks in great care and detail about the way a wall is made or a cup of tea is poured or a bird flies through the sky, it becomes something sacramental, almost, something very valuable, something to be considered in a way that we don’t consider a lot of our actions, especially when it comes to natural resources.”

In this way, Armitage wants the Laurel Prize to pursue a very different kind of change than direct political action. He wants it to celebrate the things we need to keep precious, to save, and to tend to. Maybe poetry is the perfect medium in which to do this, because, as he points out, “Poetry has always been, psychologically speaking, carbon-negative.”

I am thinking about my dream again, and the letters as large as houses. Perhaps it wasn’t just about how to begin, but quite literally about language and environment, and how we use it. “It comes back to your alphabet, you know. It’s made up of 26 letters arranged in a particular way, and it’s material, you know. The fabric it’s made from is language, and we all have language. It’s given to us as a free gift from when we’re born. And so we can all – at some level – respond to it.”

And, directed in the right way, language can also change how we see the world, as it did for Armitage growing up and reading Hughes. In terms of the climate crisis, Armitage hopes that, with this new prize, it can lend its voice to the growing chorus of concern for an issue he has always been onside with.

“Poetry on its own isn’t going to make a future difference, but it’s just a strengthening, of values, and I guess a sort of consolidation of effort. This whole prize, which is a very, very complicated thing to put together – and I’m no administrator! – came together really quickly, just by a lot of people saying, ‘We can help with this and we want to make it happen.’ ”

As our interview ends, the poet wants to add one more positivity: “This whole thing makes you feel more confident that you are not out on your own, trying to do things which are a bit hocus-pocus… It’s almost like you feel as if you’re unionising, through art.”

FUGITIVES

Then we woke and were hurtling headlong

for wealds and wolds,

blood coursing, the Dee and the Nidd in full spate

through the spinning waterwheels in the wrists

and over the heart’s weir,

the nightingale hip-hopping ten to the dozen

under the morning’s fringe.

It was no easy leap, to exit the engine house of the head

and vault the electric fence

of commonplace things,

to open the door of the century’s driverless hearse,

roll from the long cortège

then dust down and follow

the twisting ribbon of polecats wriggling free from extinction

or slipstream the red kite’s triumphant flypast out of oblivion

or trail the catnip of spraint and scat tingeing the morning breeze.

On we journeyed at full tilt

through traffic-light orchards,

the brain’s compass dialling for fell, moor,

escarpment and shore, the skull’s sextant

plotting for free states coloured green on the map,

using hedgerows as handrails,

barrows and crags as trig points and cats’ eyes.

We stuck to the switchbacks and scenic routes,

steered by the earth’s contours and natural lines of desire,

feet firm on solid footings of bedrock and soil

fracked only by moles.

We skimmed across mudflat and saltmarsh,

clambered to stony pulpits on high hills

inhaling gallons of pure sky

into the moors of our lungs,

bartered bitcoins of glittering shingle and shale.

Then arrived in safe havens, entered the zones,

stood in the grandstands of bluffs and ghylls, spectators

to flying ponies grazing wild grass to carpeted lawns,

oaks flaunting turtle doves on their ring-fingers,

ospreys fishing the lakes from invisible pulleys and hoists,

the falcon back on its see-through pivot, lured from its gyre.

Here was nature as future,

the satellite dishes of blue convolvulus

tuned to the cosmos, tracking the chatter of stars,

the micro-gadgets of complex insects

working the fields, heaths tractored by beetles,

rainbowed hay meadows tipsy with mist and light,

golden gravel hoarded in eskers and streams.

And we vowed not to slumber again

but claimed sanctuary

under the kittiwake’s siren

and corncrake’s alarm,

in realms patrolled by sleepwalking becks and creeks

where beauty employs its own border police.

And witnessed ancient trees

affirming their citizenship of the land,

and hunkered and swore oaths, made laws

in hidden parliaments of bays and coves,

then gathered on commons and capes

waving passports of open palms, medalled by dog rose and teasel

and raising the flag of air.

The Laurel Prize Day and Prize Giving was scheduled to take place at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park on 23 May 2020. See www.ysp.org.uk for updates.