At certain times of year, the crofters of my native island would practise their own form of social isolation.

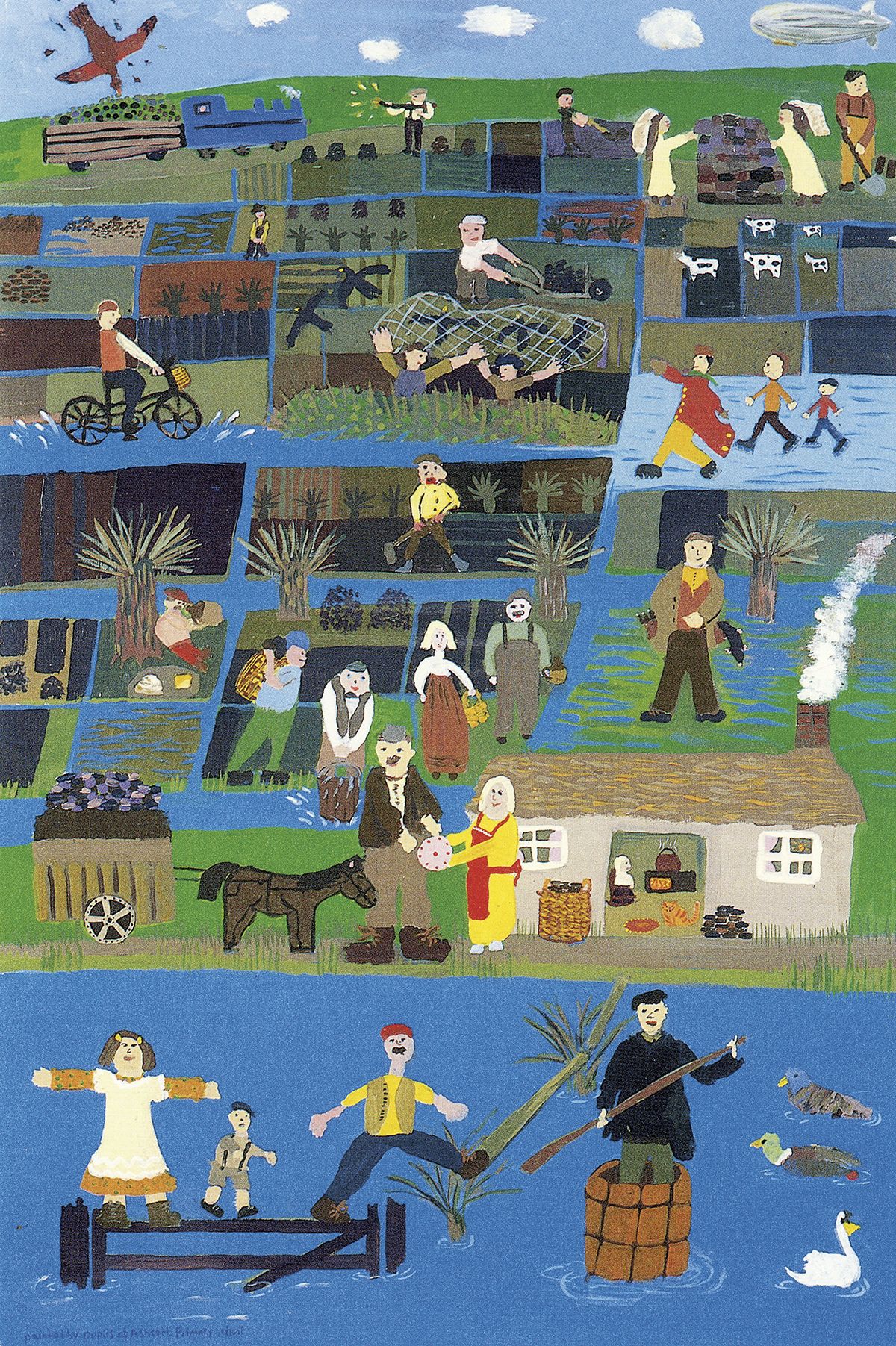

Spade, peat-blade and vacuum flask in hand, they headed out to the moor in the months of, say, April or May, conscious that this landscape was going to be the centre of their existence for some time ahead. When they reached there, they lifted their spades to scrape turf from the edge of peat-banks, carefully placing these sections at their foot to ensure that the moor’s surface remained unaltered by their labours. After that, accompanied by a partner, relative or neighbour, they dug into the darkness they had exposed, using a peat-blade to ooze one segment of fuel after another from the bog, throwing the top layer of turf on heather, building a wall with the next, squeezing out the third from the murky damp that – eventually – would provide the greatest heat and flame for their household fires.

This, of course, was not the end of their toil. There would be weeks of lifting and turning of the peats that had been cut as they were gathered and stacked in preparation for the day they would be brought home. That day was often an occasion of festivity and hilarity, community and cheer. It was especially the case when a tractor’s wheels sank below the surface, digging through turf and tiers of ‘dark stuff’, grinding and spinning until – it seemed sometimes – in true Jules Verne style the centre of the Earth might be revealed. Old enmities would be forgotten in the rush to tug and pull the trapped vehicle from the moor.

Communal moments like these are rare when people harvest peat. Most of the time it is solitary work, often back-breaking and done through financial necessity. It is not even rewarded with a great deal of heat, the first layer, especially, generating much more smoke than flame. Only the third tier, called ‘the good turf’ by Seamus Heaney in his poem ‘Digging’, is truly capable of warming people’s fingers on a winter’s night. Sometimes, as boys, we would edge closer to the fireplace during these chilly hours, balancing slices of bread on the tips of forks to make toast, scorching our thighs, creating what was then termed a stretch of ‘tinker’s tartan’ on our skin. Such red marks and patterns became our small rewards for helping our households gather peat, an activity that took up much of our summer holidays from the last years of primary school to our early twenties and beyond.

Back then, we never reflected on how fortunate we were, ‘working in the peats’ on a small Hebridean island. The neighbourhood celebrated to mark the day a fresh haul of peats was stacked beside our home. No bosses harangued us to work harder – only Mum and Dad. We reaped, too, what we had sown, our fires the result of our own industry. There were even small moments of delight. I can recall stories told and jokes exchanged while sprawled out on the heather sharing tea and scones. Gaelic songs might be sung. And of course there were the moorland birds. Their cries punctuated our work, diverting us from the strain of all our physical effort. The weeping of a guilbneach or curlew. The pirouetting of the lapwing or curracag. The dreathan donn or wren perched on the wall of peat not far away.

Most of all, however, there was no sense that we were experiencing real hardship while undertaking this work. This was unlike many of our counterparts on the continent of Europe. The once extensive peatlands in the Netherlands formed the basis for its heavy industry. Without any large seams of coal, the country relied on peat for the production of many of its goods. This was also true of Germany, a nation that until the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–1 possessed very little coal within its borders. One could even argue that it was the lack of this fuel that partly caused the outbreak of the first world war, with both France and Germany depending on it for their heavy industry and desperate to gain control of the coal mines in regions such as Alsace.

Not only were these peatlands industrial, but they also formed the basis of the systems of both punishment and reform in the Netherlands and Germany. Beggars, thieves and prostitutes from cities like Amsterdam and The Hague were sent to areas like Veenhuizen in Drenthe in the hope that the peatland might redeem them, turning these wayward souls into upright citizens. This approach reached its nadir in the first camps created by the Nazi government when they came to power in Germany. These occurred in places like Esterwegen in the district of Emsland near the border with the Netherlands. The political dissidents and Jews trapped behind the barbed wire were sent each day to cut peat, transforming the landscape while providing fuel for local homes and industry.

With this in mind, it is little wonder that throughout much of Europe the existence of the moorland has spawned a thousand ghost and horror stories. This was even true of my native Lewis, where Mac an t-Srònaich, a legendary 18th-century murderer, was said to haunt the empty acres. Yet there has always been much more to the moor in these islands than this. The shielings, or airidhean, built near the lochs or hillsides of the Highlands and islands were places where young people could find romance and excitement, far away from the prying eyes of fellow villagers. The moor’s plants and flowers – bog-bean especially – could provide a cure for illness. Its mosses provided colour for cloth and tweed. The delicacy of its shades, its heights and dips, inspired a thousand songs, particularly in my other tongue, Gaelic.

Most of all, it was home for a range of wildlife – deer, eagle, hen harrier, lapwing, snipe – that lifted the spirits of all who stepped on it, exploring its breadth and depths.