The explosion of Black Lives Matter protests across the world has reignited calls to teach colonialism in schools, with campaigners in Britain demanding that the curriculum teach the violent realities of its empire. They insist that incorporating colonialism into the curriculum will provide the British public with a better understanding of how systemic racism began, and how it can be dismantled today.

During the colonial era, racial hierarchies were created to justify the exploitation of lands and the enslavement or extermination of people. In modern society these hierarchies are perpetuated through institutional racism, exemplified in Britain by the disproportionate number of black, Asian and minority ethnic people killed by Covid-19, the Windrush scandal, the Prevent strategy, and police brutality against black people. Globally we are witnessing another way black, brown and Indigenous people have been disproportionately affected: the climate crisis. A crisis that is rooted in colonialism.

The first colonisers stepped foot in the Americas with an insatiable drive for natural resources – at the expense of people and the land. Since 1492, wealth from natural resources and slavery has been channelled from the colonies to European nations. This wealth fuelled the industrial revolution responsible for the initial, mass emission of CO2 in our atmosphere. Carbon maps show that Europe and the US have historically emitted the most CO2, which remains in the atmosphere for centuries and continues to warm our planet.

As the world heats up, it is the countries least responsible for rising carbon levels that are the most affected by it. Global South countries will be affected by the climate crisis first. As a result of the ravaging of their economies by centuries of colonialism and imperialist extraction, and the consequent lack of infrastructure and capital, they are the least able to implement adaptation measures. Meanwhile, in the Global North, people of colour are also feeling the effects of the climate crisis more acutely than their white counterparts. Black British people are more likely to breathe illegal levels of air pollution than their white British counterparts and – as we saw during Hurricane Katrina in the US – when natural disasters hit, black people are less likely to be protected by government measures.

Learning about colonial history will help us understand the detrimental effects Britain has had, and continues to have, on the rest of the world. Britain is responsible for the climate crisis not only because of its historical emissions of carbon dioxide, but also through its contribution to neo-colonialism and the extractivist economy. The UK’s role in worsening the climate crisis is manifest where its economic power lies: the City of London. The London Stock Exchange generates a fifth of the UK’s GDP, with many of the businesses listed responsible for 70% of global emissions. A stark inequality and the colonial relationship with the Global South is highlighted by noting that the fossil fuel shares on the London Stock Exchange are worth more than the entire GDP of sub-Saharan Africa.

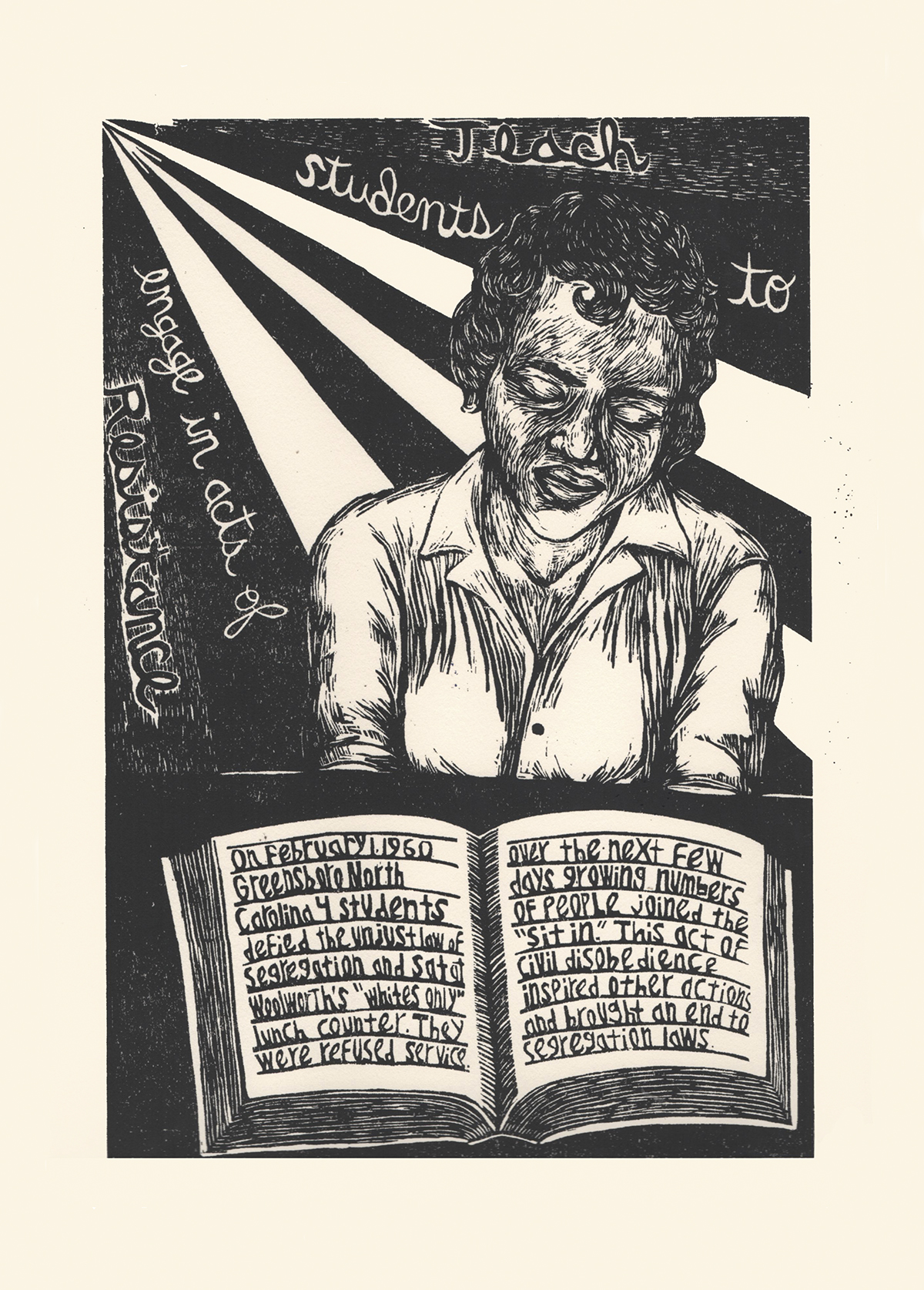

Teaching colonialism in schools should include not only the brutalities that European colonisers inflicted on the Global South, but also the history of Indigenous and black resistance. This vast, global history, spanning many centuries, encompasses the Haitian Revolution, the Mau Mau Rebellion in Kenya and the 1936 Arab Revolt in Palestine, as well as more recent examples such as land defenders in Nigeria against Shell. A curriculum that included this resistance to colonialism would combat the racist notion that all that is needed is an intervention by ‘white saviours’. Instead, it would ground young people in Britain in the remarkable experience of organising against colonialism.

These histories would inspire young people to look to black, brown and Indigenous climate activists across the world today, including Philippine typhoon survivors taking legal action against the world’s largest CO2 polluters, and the Wet’suwet’en First Nation in Canada fighting a proposed gas pipeline. They would also propel them to look closer to home for anti-racist climate activism, such as Black Lives Matter UK shutting down London City Airport in 2016 to bring to light that the “climate crisis is a racist crisis”. Teaching colonial history would contribute to an ethic of active involvement against colonialism and the disaster it has reaped on the environment.

Meteorologists predict that 2020 will be the hottest year on record. To put out this fire, we must ensure our fight for climate justice is rooted in a concerted opposition to a system that disregards people’s lives simply because of the colour of their skin. This same racism keeps black people in areas with high levels of pollution and justifies sacrificing people in the Global South by continuing to plunder their land. Understanding colonial history, and being prepared to challenge its modern manifestations, is to stand with the anti-racist struggle and fight for climate justice today.