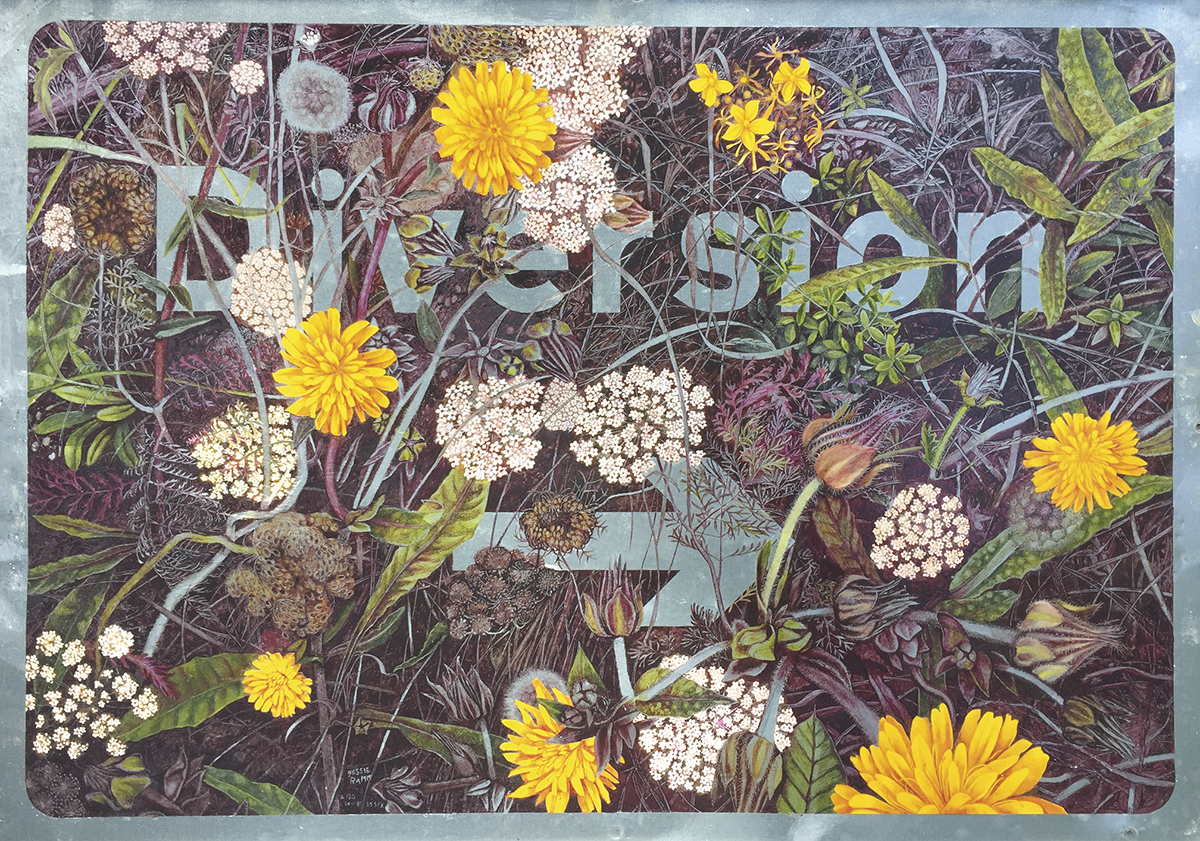

Back in 2013, Richard Mabey said that if it is possible to say that Nature writing has a common spring, it is one that is “defiantly anti-pastoral”. That is, “It emerged not out of a desire to return to some ruralist golden age, but to repudiate such fantasies.” Rather than concentrating on the simplified bucolic, focus has sharpened on the unfarmed wild, on urban and suburban edgelands, on the small, the local and, in the case of Stephen Moss’s most recent book, the hidden corners of Britain that he calls (in a nod to Mabey’s The Unofficial Countryside) the Accidental Countryside.

Moss’s starting point is the acceptance that Britain’s wildlife is under threat. Loss of habitat, coupled with pollution, persecution and the global climate emergency, has resulted in the collapse of ecosystems and in population declines in what were once common and widespread flora and fauna. While he contends that fragments of our conventional countryside are still home to numerous species, Moss suggests that it is the existence of other habitat that is crucial for wildlife’s survival: places that are forgotten, neglected, marginal and exist, as Kenneth Allsop said and Moss quotes, in “that messy limbo that is neither town not country”. However, The Accidental Countryside goes further than previous books on edgelands. Alongside a wide range of rural, urban and suburban settings, Moss also outlines the importance of what he calls “the alternative countryside”: those locations that have outlived their original purpose and have now been transformed into Nature reserves.

While the concept of edgelands may seem distinctly modern, Moss makes it clear that the Accidental Countryside is not confined to the modern, post-industrial landscape. During a visit to Mousa Broch, an Iron Age stone building on the eastern side of Shetland, he watches as several thousand storm petrels return to their nests inside the walls after several days at sea. Following visits to Skara Brae on Orkney and the Iron Age hill fort of Barbury Castle in Wiltshire (whose earthworks act as a suntrap for butterflies), Moss reflects on how parts of our landscape change over time, “to the point of covering up the very evidence that humans ever lived there at all, and the process by which wildlife takes them over is long and often complex”.

The book is as detailed as it is fascinating, with Moss tracing the history and development of each part of the Accidental Countryside in turn. Dr Beeching, so often pilloried for his closure of a third of British railway stations, is “grudgingly” recast as an almost-hero thanks to his unwitting creation of thousands of miles of wildlife corridors. Moss explains that even the rise of the motor car, one of the engines of the climate crisis, has created space for Nature: Britain’s 300,000 miles of road verges contain more than 700 species of wild flower (nearly half the UK’s total), of which almost 100 are threatened with extinction. Moss reminds us that these forgotten places – this accidental countryside – have never been so important, especially at a time when we have lost 97% of our ancient flower-rich grasslands.

But the sum of Moss’s book is even greater than its parts. In asking us to look again at the UK’s crowded landscape, he is demanding that we reframe how we think of Nature, encouraging us to recognise the constant interaction between human and non-human worlds. His perspective offers not only an important history, but also a glimpse of a potentially brighter future.