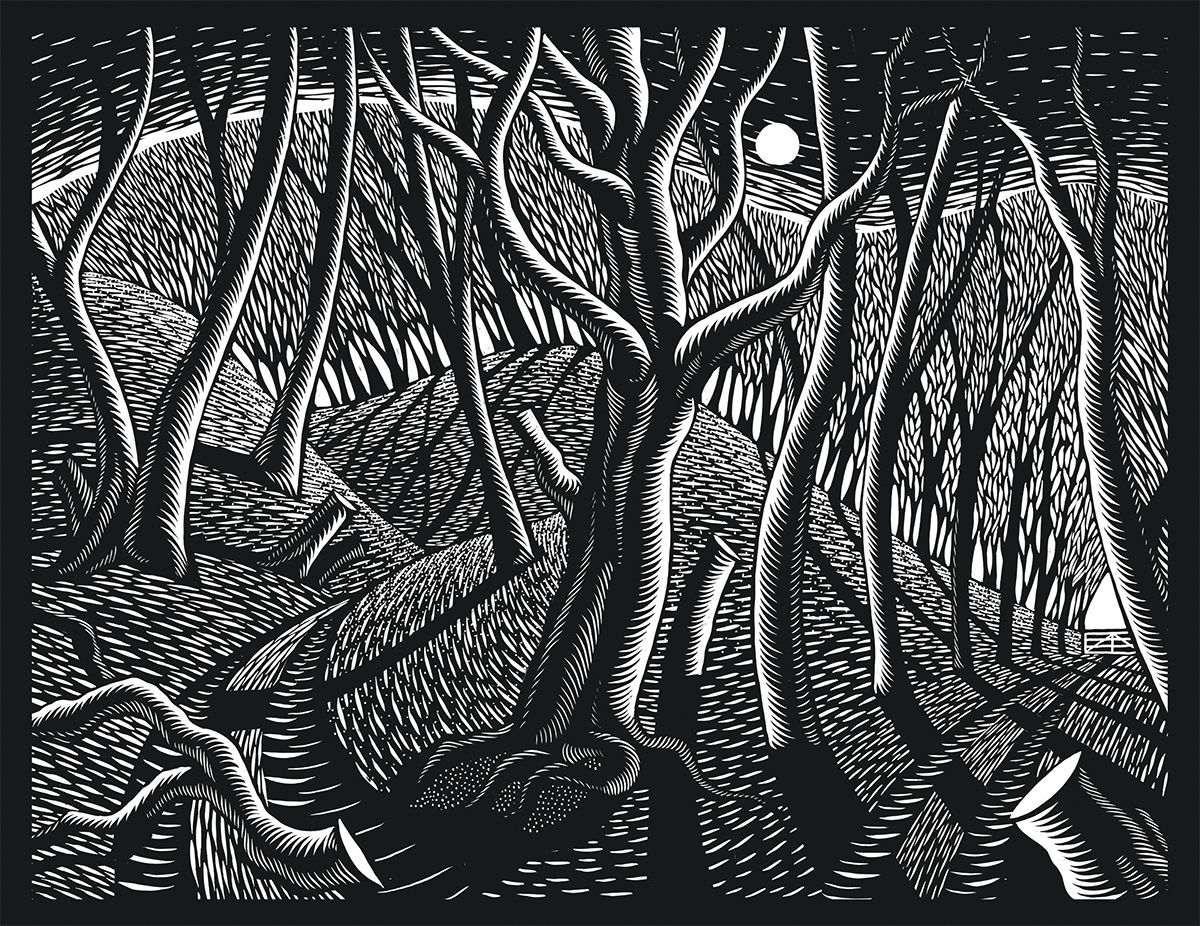

We have been asleep. We take our weekend walks down permissive footpaths, hemmed in by barbed wire. We have been excluded from 90% of England’s land and 97% of its waterways. ‘The commons’ has become a romanticised notion of an almost mythic past. Even the free parties of the early nineties have morphed into the boutique festivals of today. On whose watch did 1% of England’s population end up owning half the country? And how might we take some of it back? At the end of the first chapter of The Book of Trespass, Nick Hayes finds himself at the closed gates of an estate close to his childhood stomping grounds. “I put my hands on the flint wall,” he writes, “and climb over.” It is that simple. And as he does this, he lifts the veil upon this other, hidden England.

Trespass and moral failure have long been spoken of as two sides of the same coin: we talk of crossing the line, being on the straight and narrow, straying from the path. Hayes embraces this, roaming the estates with a merry cheekiness, rolling joints, cooking bangers over his campfires and skinny-dipping in the ornamental ponds. But the act of trespass itself is legally slippery, and as the book unfolds, and as Hayes strays across the country, he simultaneously walks us through the philosophical and judicial developments that have come to allow an individual to assert ownership over what once was common heritage. It is a story that goes back to the Norman Conquest and unfolds through the enclosures of England’s own common land before we exported the model to the colonies.

And as the boundary walls went up, they went up also in our minds, “a manmade spell”. This most glaring of injustices is right beneath our noses but goes mostly unheeded – it is just the way things are. The commons, a model that would have been familiar to our ancestors, now sounds ludicrously utopian. In his gentle acts of deviance, Hayes smashes down these walls. Tramping through these vast estates, he invariably sees no one; his transgressions start to put paid to the ideology that England is a country running out of space. And, as he reminds us, each of his trespasses would in Scotland be legitimised under the right to roam. Rather than a crime, these walks and campfires are his birthright. Once one has seen the land another way, he writes, it cannot be unseen.

Nothing that Hayes proposes is particularly revolutionary. An expansion of the Countryside Rights of Way Act that would allow us to camp and roam more widely exists not just in Scotland but also in much of Scandinavia and Austria. A less murky version of the Land Registry, where you could find out, for free, who owns the land around where you live, is present in many European countries, but not in England. A land value tax, whereby landowners would pay a tax to the people, was supported by both Adam Smith and Winston Churchill and exists in countries from Russia to Taiwan, and a version was used to raise revenue for Crossrail.

Hayes makes a convincing case that improved access to land underpins many other battles, from poverty reduction to food security, affordable housing to tackling climate change. Yet any mooted reforms are typically framed in a certain section of the press as Marxist garden taxes and Zimbabwe-style land grabs. There is a lot still riding on maintaining the illusion that an Englishman’s home is his castle. But in Hayes’ work, and in other publications of recent years, there is a growing feeling that the commons are stirring once again.

For more information: www.righttoroam.org.uk