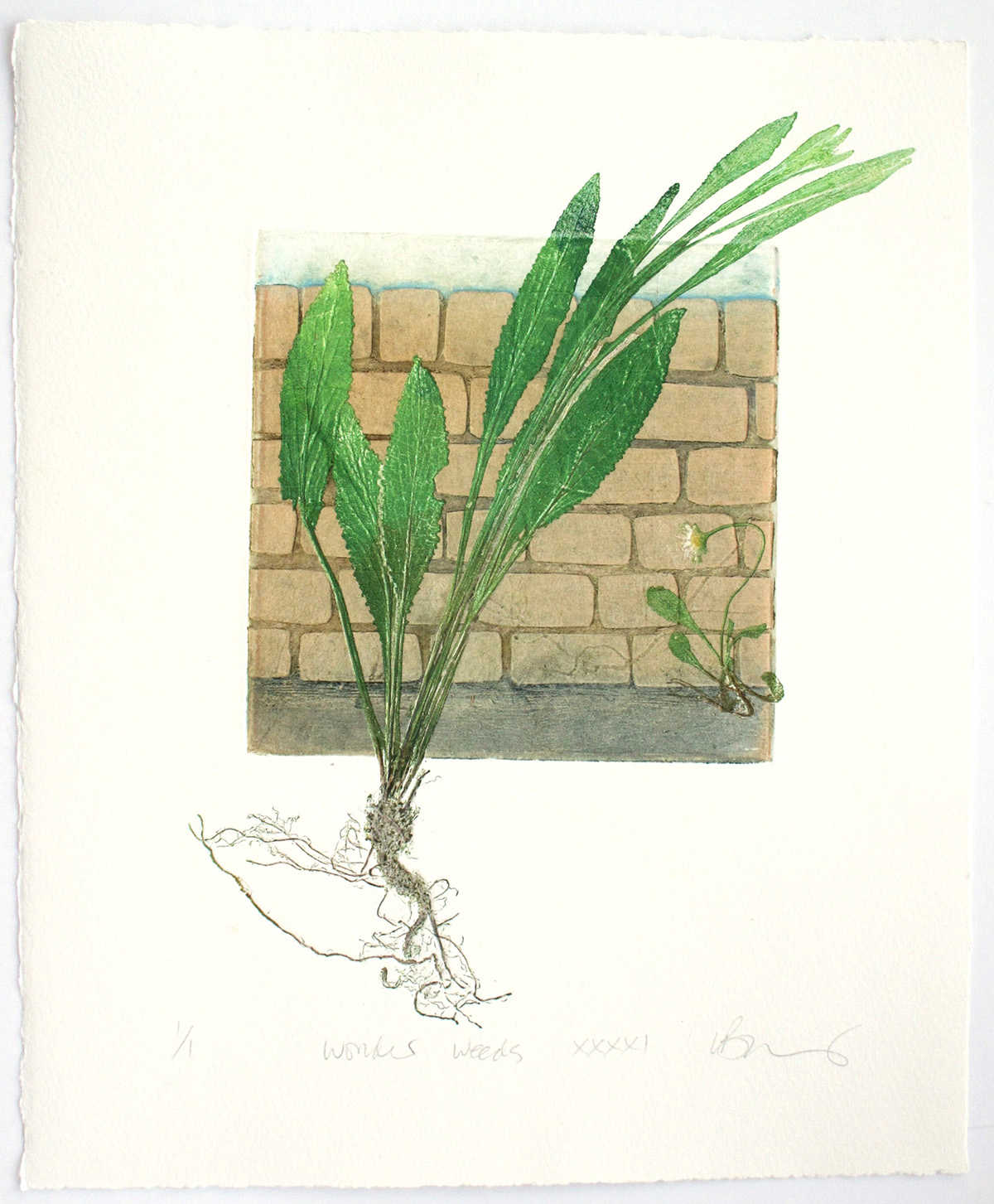

Back in spring 2020 I began to notice pavement plants. As our local suburban wood swelled with visitors, and trips to Nature reserves felt irresponsible,

I walked the locked-down streets of south London instead. The simple rhythm cleared my head, but increasingly I tuned in to the details of street trees and opportunistic weeds too, the latter benefiting from our council’s benign neglect. I greeted the flowers I could identify and photographed the ones I couldn’t. And I wondered about them.

Seven months on, and beauty is not a word that immediately springs to mind in this unremarkable 1950s housing estate in Streatham, but that is what we are looking for on this warm autumn morning. I’m meeting botanist Roy Vickery and others to enjoy the weeds growing on the estate’s pavements. Vickery has been sharing his knowledge with urban plant enthusiasts for over 35 years and I’m exceptionally excited to be out with an expert today.

“My plant walks are mainly on city commons and cemeteries, but a couple of years ago I started leading walks here,” he tells me.

Eyes down, we progress painstakingly around the estate, identifying and listing weeds as we go. There are still a number in flower, probably benefiting from the milder temperatures – the urban heat island effect that many cities experience.

There is no plant discrimination here. We enjoy equally the beauty of wild plants and garden escapees and the stories Vickery tells us about them. First we find the unassuming yellow-green flowers of common groundsel, which poor people in Victorian times collected to sell as food for caged birds. In a corner, bristly clumps of green alkanet are thriving, a plant in the forget-me-not family that made its escape from gardens in the 18th century. The vivid yellow flowers of catsear dot the verges, the tiny leaf-like scales that clasp the stem giving this plant its name. A lone black nightshade has found a refuge by a fence, the shape of its white and yellow flowers contrasting with the black fruit and revealing it’s in the potato family.

I’m part of a long tradition of London plant enthusiasts valuing urban weeds, from Edward Salisbury’s second world war bombsite plants to today’s street botanists who blog about the weeds they find. At the start of 2020, Sophie Leguil, social media botanist and passionate advocate for urban plants, launched her campaign More than Weeds. Inspired by the weed-labelling campaign in Paris, she has highlighted the importance of pavement plants for invertebrates and argued against the use of glyphosate weedkiller on our streets. After attending an online talk, I asked her what was the most interesting pavement plant she’d found in London.

“It’s a garden plant called harestail, a grass with lovely pompom-like flowers,” she told me. “It made me smile. I’m a botanist, but you don’t always need to see plants in a scientific way.”

It would be hard to appreciate weeds growing in pavement tree pits without relishing the trees they encircle too. Author and urban tree enthusiast Paul Wood was amazed at the interest when his book London’s Street Trees was published in 2017.

“It’s as much about the human stories as the botany,” he told me. “Everything from the plant hunters to the social and architectural decisions that informed their planting. These are the things I continue to find fascinating.”

Fired by Wood’s enthusiasm, I became much more aware of the trees I passed. On a routine trip to the shops, I found an extraordinary spray of chestnut-coloured seed cases that had fallen onto the pavement from a tree with large heart-shaped leaves. Back at home, a little detective work revealed that this was a foxglove tree, native to China. Since then I have found excuses to visit it every few weeks as this year’s fruit is formed.

Whilst today Vickery is showing us weeds originating from South America to South East Asia, the star of the show for me is a tiny plant from the Mediterranean. The prosaically named four-leaved allseed, which probably hitchhiked to London in plant pots, isn’t common, but Vickery tells us this estate is its stronghold. Using my magnifying lens, the details of a tiny sprig are revealed, and I can see the intricate multi-seeded fruit that gives the plant its name.

My local pavements have become places to pause and enjoy weeds and trees, rather than simply being my path out of the city. US artist Mark Tobey said: “On pavements and the bark of trees I have found whole worlds,” and I’m out there walking the streets of south London in search of those worlds.