Like many people, I was blown away by Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk, a memoir that set the death of her father alongside her training of a goshawk, a recalcitrant and bloody-minded raptor. Her battles with the bird mirrored her battles with her grief in a manner both devastating and transcendent. Yet the book’s success and many accolades spawned an entire subgenre of Nature writing whereby the author undergoes some personal transformation echoed in the non-human subject of their choice. Many of these books feel tin-eared and derivative to me, and it is exactly this need that Macdonald explores in her stunning collection of new essays: our yearning to find a foothold in the natural world to deal with our own muddled emotions.

Macdonald describes her collection as a sort of Wunderkammer, a cabinet of wonders – like those cases of natural and artificial curiosities in certain stately homes some centuries ago. As important as the objects were themselves, it was the reading of their relations, the juxtaposition of seeing such items side by side that provoked a feeling of wonder in the observer. These individual essays are about badgers and ants, goldfinches and swans, but through their constellation Macdonald is able to get at something fundamental about the human condition.

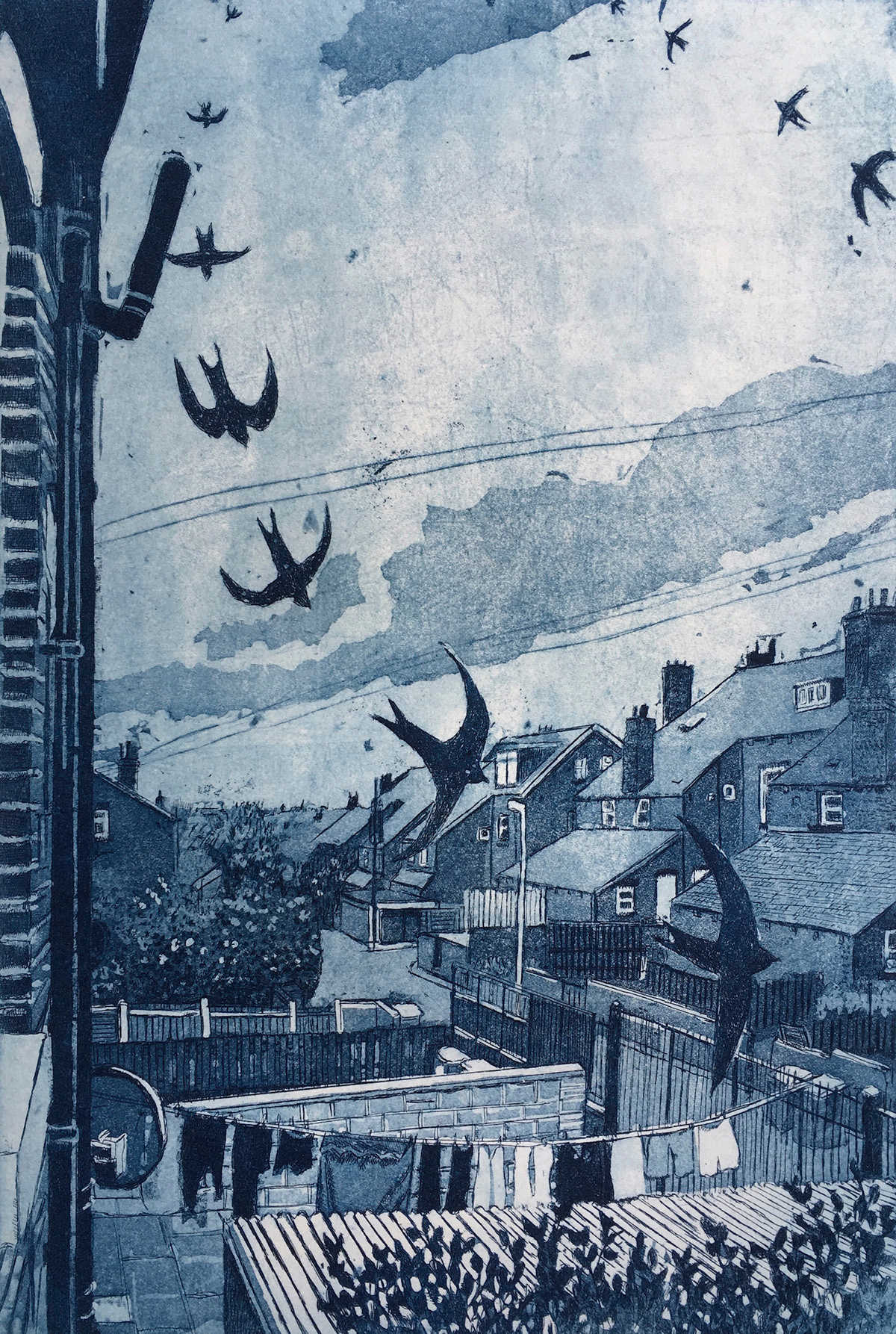

Although the essays take in a wide swathe of British wildlife, birds, Macdonald’s foremost passion, are never far away. In the first essay, ‘Nests’, she writes that when she was a child they “challenged my understanding of the Nature of home in so many ways”, and it is this restlessness of spirit, in some sense bestowed on her by birds, that permeates her writing. There are essays about the Olympian migrations of cuckoos and storks, about human migrants in search of home, about the migratory creatures that make a mockery of borders. She follows a scientist high onto the plateaus of the Atacama Desert on an expedition to get a sense of what life might exist on Mars.

Macdonald has a flair for noticing what the rest of us might walk past: a column of ants spiralling into the air in their annual mating dance; a small flock of rare waxwings on a busy shopping precinct. “I am far from an industrious soul,” she writes, “except in my capacity, perhaps, to pay close attention to things.” Frequently the naturalist’s close observance and appreciation of minutiae is juxtaposed with the parochialism of the English character. During the war, feeding birds became a national pastime as the protection of our garden birds took on a kind of nationalist fervour. In 1934, when Norfolk farmers learned that the skylarks eating their wheat were migrants from the continent, they shot them for perhaps having sung to Nazis. In times of crisis, Macdonald suggests, we search for meaning in what is close at hand. Perhaps that is the reason for the explosion in new Nature writing. And yet ultimately she makes the case that by coming to notice and to know better our own patch, we come to better inhabit the world: not just our own patch, but all of it.

Animals can teach us things. They are not trivial, unintelligible parts of our lives, and to believe that is not to Disneyfy them. They are repositories for our hopes and fears, and what we think about them says much about what we think about ourselves. Macdonald describes our animal encounters as like reading the Tarot, in their ability to provide inexplicable, irrational insights into our own deepest emotions. And, she writes, “on my travels I’ve talked to many strangers about grief, and birds, and love, and death.”