After barely moving for 20 minutes or so, the reality sank in. We are stuck in a monumental traffic jam on the M25. In the far distance, the graceful arc of Dartford bridge across the Thames on the east side of London. Shimmering specks of cars and trucks end to end. Static. Nothing moving on the hottest day of the year. We begin to cook in our little plastic box.

Smartphones scour the internet for information. The AA site tells us that we could be in for a four-hour wait on this Sunday afternoon. Ducting from a bridge on the southern approach to the crossing had fallen on passing vehicles. Bits of infrastructure collapsing under the stress of heat in this changing climate.

We curse ourselves that we took the car across London and not the train. That we were subject to our laziness. Falling for the apparently easy option. We stare at the endless line of cars and trucks. There must be the population of a town in this jam. All engines running, keeping the air con on. Constant combustion in the myriad piston chambers. Fire on the bridge.

We can see the towers of Canary Wharf 20 miles west, shrouded in hot smog. Just downstream of us, at the Navigator oil terminal with its cluster of grey tanks, is a ship unloading at the jetty – Pyxis Epsilon. An internet search reveals her to have arrived after a voyage of two days and four hours from a refinery at Brofjorden in Sweden. Delivering petrol or diesel to London. Delivering carbon into the atmosphere. Fuel for the fire.

Twitter picks up distress calls from other cars: “I have three young children in here. We need water. Please can someone deliver water? How long until we escape from this?”

The UK government is pushing forward the construction of another Thames crossing just east of here, claiming that it will relieve traffic at Dartford, but this expansion of London’s roadways will encourage more road users and doubtless produce yet more jams like this. Amidst the summer madness we remember that this temporary hell is the outcome of a dream.

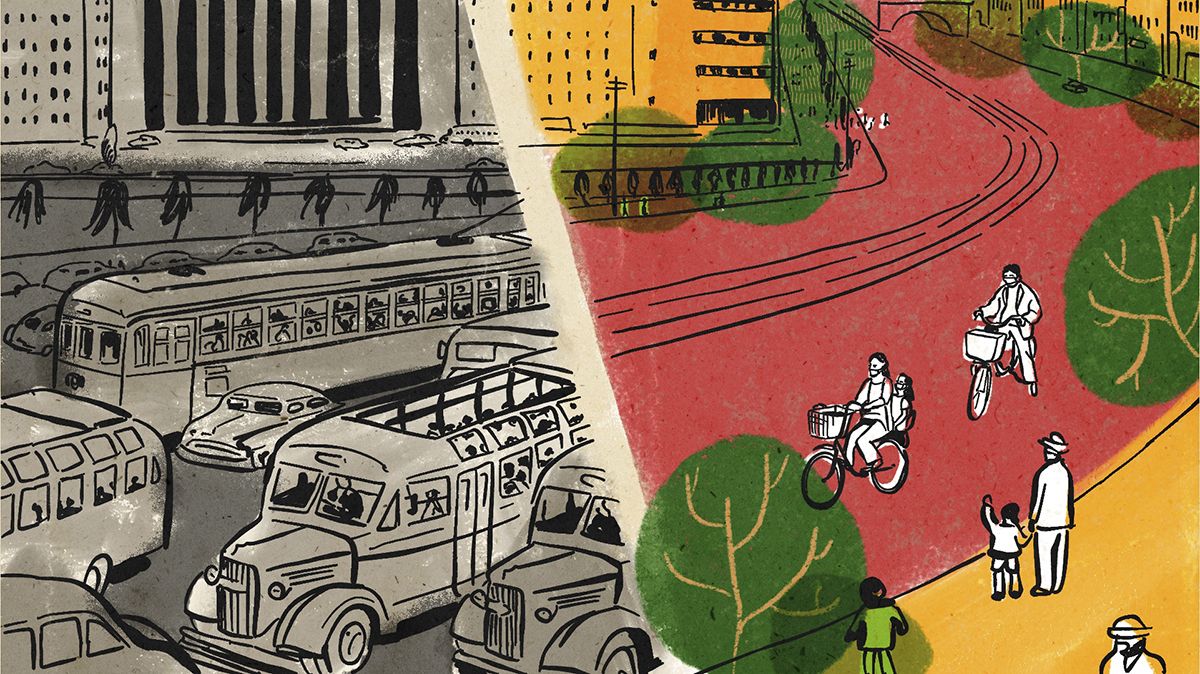

In the Blitz of the second world war, parts of London were destroyed by Luftwaffe bombs, laid waste by petroleum-fuelled aerial attack. Among the ruins, a team led by Patrick Abercrombie delineated a vision for a new city in the Greater London Plan. Published in 1944, the proposal was in essence an oil city that would be “the centre of Empire”. The president of the Royal Geographical Society said in response to its first presentation: “Their dreams may not take practical shape as they have dreamed them, but in what they have done they have started the younger generation on the road that they have to travel if their London is to be more worth living in than the slummy ramshackle London that older men like myself have known and loved.”

Together with Terry Macalister, my co-author of Crude Britannia, I have studied the 1944 plan. We have gazed at the blotches of purple, brown and green designating areas for industry, housing and parks, and seen the world we’d grown up in. Here are the New Towns such as Harlow. Here are the future airports of Heathrow and Gatwick. And here, circling around the metropolis, is the broad white line of what would become the M25, with its crossing of the Thames at Dartford. This bridge was not completed until 42 years after the publication of the plan. The plan induces a feeling of vertigo as we realise that this city region – which includes this motorway – was in part designed by a handful of men operating within the empire. The plan depended upon extracting fossil fuels from expendable parts and expendable peoples of the planet. This bridge, which feels so contemporary, sprang from imperial minds.

Nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century London had evolved out of the coal mines of England and Wales. Coal – cheap because capital was not invested in improving working conditions and because miners’ wages were so low – had made it possible to build the largest city in history. Cheap coal had fired the kilns that turned clay into innumerable bricks. Cheap coal had glowed in the narrow grates of millions of poorly insulated rooms. Cheap coal had fuelled the trains that brought the labour and its sustenance into the metropolis. Cheap coal drove the power stations that generated the electricity running the trams and Underground. Without cheap coal there would have been no modern London.

Abercrombie’s plan was for an imperial London with oil as its foundation. It marked a shift from a coal city to an oil city. The New Towns were built around the motor car. Civilian airports blossomed and aviation fuel slaked the thirst of thousands of planes. Oil made possible the arterial roads such as the A40 Western Avenue and the A12 Eastern Avenue, designed not to carry electric-powered trams, but diesel-driven trucks and petrol-fuelled cars. Soon afterwards, the motorways, such as the M25, followed this model. Oil – cheap because it was extracted from colonies such as Nigeria and parts of the ‘informal empire’ such as Iran – depended on environments that could be sacrificed, on low-wage labour and on colonial power. Not only London was rebuilt on an oil foundation, but every city in Britain, from Glasgow to Liverpool, from Cardiff to Newcastle. Bricks, tarmac and concrete entrenched Crude Britannia.

The sheer appetite of a metropolis for devouring oil has long been understood. Writers such as Herbert Girardet in the 1980s pointed to the tankers in the Thames Estuary that were feeding the engine of London. That we should be stuck in a traffic jam resulting from Abercrombie’s 80-year-old vision can induce a sense of fatalism, but it also points to the power of dreamers, how long their dreams can take to be realised, and how those dreams can turn into nightmares.

However, there are many who are dedicated to leading us out of the nightmare of a misshapen city, a great bonfire that drives the climate into chaos. The Thames Crossing Action Group is challenging the plan to expand the M25 and build another crossing. Initiatives such as London LEAP are pioneering ways of tackling climate justice by building up from community groups rather than down from central planners. Elsewhere Merseyside Labour for a Green New Deal is pioneering the transformation of Liverpool, and mPOWER is bringing together 26 cities across Europe to assist democratically driven schemes to reduce carbon. All of these projects, and a myriad more, are leading us out of the century-long traffic jam, away from the geological pyre of the Oil City.

For more information:

Platform London: platformlondon.org

Thames Crossing Action Group: www.thamescrossingactiongroup.com

London LEAP: tinyurl.com/london-leap

Merseyside Labour for a Green New Deal: www.facebook.com/MerseyLGND

mPOWER: www.municipalpower.org