Citizens from more affluent areas of the UK are 50% less likely to die from Covid-19, and those of black ethnicity are four times as likely to die from the virus compared with those of white ethnicity. This data collated by The Health Foundation shows how the pandemic has dramatically exposed the consequences of radical inequality. Compounding this, in a recent BBC interview, cardiologist Aseem Malhotra made clear that the biggest driver of demand on the NHS is diet-related disease, and that some calculations had estimated that half of all Covid deaths could have been avoided with healthier lifestyles. How have we come to be a society where such radical inequality (not only financial but also in the ability to influence political outcomes) leads to lack of choice and capacity for the poorest to tackle the drivers behind the Covid-19 pandemic by providing healthier life choices for their children and families?

Institutional inequality is ingrained into the structures of economic governance and into our political economy. This means that, given the evidence that better health and economic outcomes for the whole of a society are determined by the distribution of equality rather than its overall wealth (according to Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson in their book The Spirit Level), such institutional inequality will continue to drive a sense of scarcity that then excuses the growth addiction in the richest. This is leading to the positive feedback loop we are caught in that is exhausting our planet towards mass extinctions. As economic anthropologist Jason Hickel argues, demanding greater equality used to be part of a radical left-wing agenda, but now it is necessary for our survival.

This positive feedback loop of institutional inequality enables the practice of market fundamentalism or extremism, where the market no longer remains a function of a society, but starts to take over and become the society itself. Thus it is becoming standard for law and policy to enable social goods – child education, medical care, eradication of poverty, and so on – to be allocated and distributed through market relations. Charities and schools are now often run as if they were corporations, prisons are run by private companies, and the services of the NHS are being de-bundled and sold off. The expansiveness of human experience itself – joy, grief, pain and love – is being shunted and boxed into the frame of a market relation.

This article attempts to make visible the impacts of such inequality so that it can be rejected as an injustice on everyone, providing one glimmer of hope to stepping outside of this path through the pioneering steps of Wales and Scotland before it. The route begins through our cities.

A GOOD ACT TO FOLLOW

A legal tool for visibilising this inequality has recently come into effect in Wales (and has been in effect in Scotland since 2018). The Equalities Act 2010 is a piece of legislation that prohibits discrimination and the unequal treatment of citizens according to individual protected characteristics such as disability, age, race, belief and sexual or gender orientation. However, set out at sections 1–3 of that Act are ‘dormant’ provisions that the UK government did not bring into effect for any of its nations. These provisions set out a factor for equality that is separate to and distinct from those of individual characteristics.

It is worth noting that the legacy of equality enshrined in the Equalities Act 2010 was led and championed by Bob Hepple, a lawyer from South Africa who represented Nelson Mandela in his struggles against apartheid and, following reprisals against him by the South African state, sought asylum in the UK and brought the wealth of his lived experience with him. It has been said that Hepple’s biggest intellectual contribution to the 2010 Act was the provision that would have required government to pay due regard to the need to eliminate socio-economic disadvantage. However, although the legislation was passed with cross-party support, this provision was not enacted after the change of government in 2010. That is why Wales independently bringing sections 1–3 of the 2010 Act into force for its people (as did Scotland) is such a radical and pioneering step.

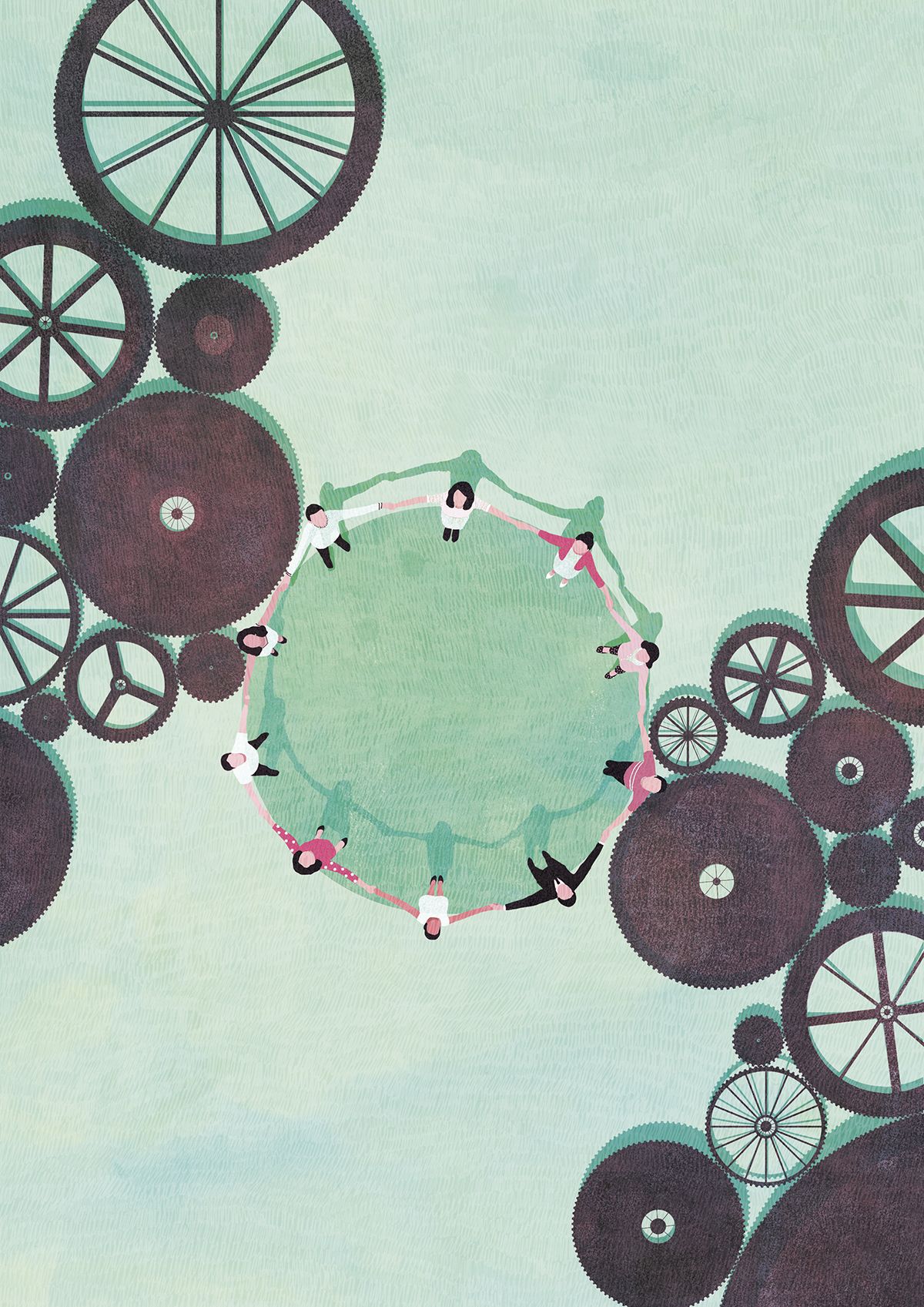

New Municipalism offers another route to devolution, attempting to bypass the stranglehold that the State has over allocation of resources. There is no one single theory for New Municipalism, but its aim is to bring agency to local people situated in their local places, so they can determine those factors that make up the quality of their lived experience. Whilst local government is an important actor within New Municipalism, recently it seems that some local authorities are attempting to put themselves into the driving seat for New Municipalist practices rather than being in service and limiting themselves to enabling the democratisation of economic decision-making at the hyper-local level.

CITY-CENTRED PRACTICE

New Economy Law has been involved in some experiments in what could be called ‘Co-liberatory Municipalism’. This is the bringing together of a co-liberatory understanding (where agency to reduce inequality is put in the hands of those most impacted) and New Municipalist practice, where the site of experimentation is the city, with its diverse range of people of different values and ways of looking at the world rubbing up against each other in daily small interactions.

One of those experiments centred on the Cultural Contract initiative by the Welsh government/Arts Council Wales, which proposed to distribute £53 million to the Welsh arts and cultural sector, with an expectation that organisations receiving such funds would agree to a cultural contract setting out how those funds would be used to meet additional wider objectives such as inclusive leadership, fair work and environmental justice. New Economy Law supported a range of young adults in marginalised communities in Butetown, Cardiff, to make some recommendations to the Welsh government/Arts Council Wales through the Wales Cultural Alliance. One of the starkest facts to surface was that, whilst many of these young adults saw themselves as creative, not one of them had been to any of the mainstream cultural and arts programmes on offer in Cardiff, because they did not feel that what was offered spoke to them and their needs. We arrived at a set of recommendations centred on their assertion that they did not want to be seen merely as beneficiaries of the economic agency of others with more structural privilege, but rather saw themselves as agents for economic and social justice, levelling up their own interests, which often get left behind when they are only represented through others.

Whereas State-entrenched institutional inequality is creating the conditions for a socio-economic force that is pulling us further apart and driving a sense of scarcity that excuses growth addiction, a co-liberatory approach to New Municipalism is concerned with networked agency in the hands of those most impacted and outside of the pull of the State as far as possible: a “politics of proximity”, in the words of scholar Bertie Russell, for shaping the conditions for a socio-economic force to pull us closer together, thereby reducing the anxiety of scarcity feeding the growth addiction. The legacy of Hepple, through the socio-economic duty now brought into force for Wales and earlier for Scotland, provides an opportunity for these nations, their cities and their peoples to take a catalytic leadership role in demonstrating an alternative route outside the rush to the precipice in which growth addiction is taking global society.