The UK’s 2019 ‘State of Nature’ report found that populations of our most important wildlife had fallen by 60% in 50 years, an unprecedented and spectacular decline. As we concrete over the UK, spray every crop multiple times, and wipe out our wildlife in the process – the UK is said to be the most wildlife-depleted country in Europe – we can pause to ponder what the future holds for us. A land of humans, feral pigeons, rats, and nothing much else? It is looking more likely every day.

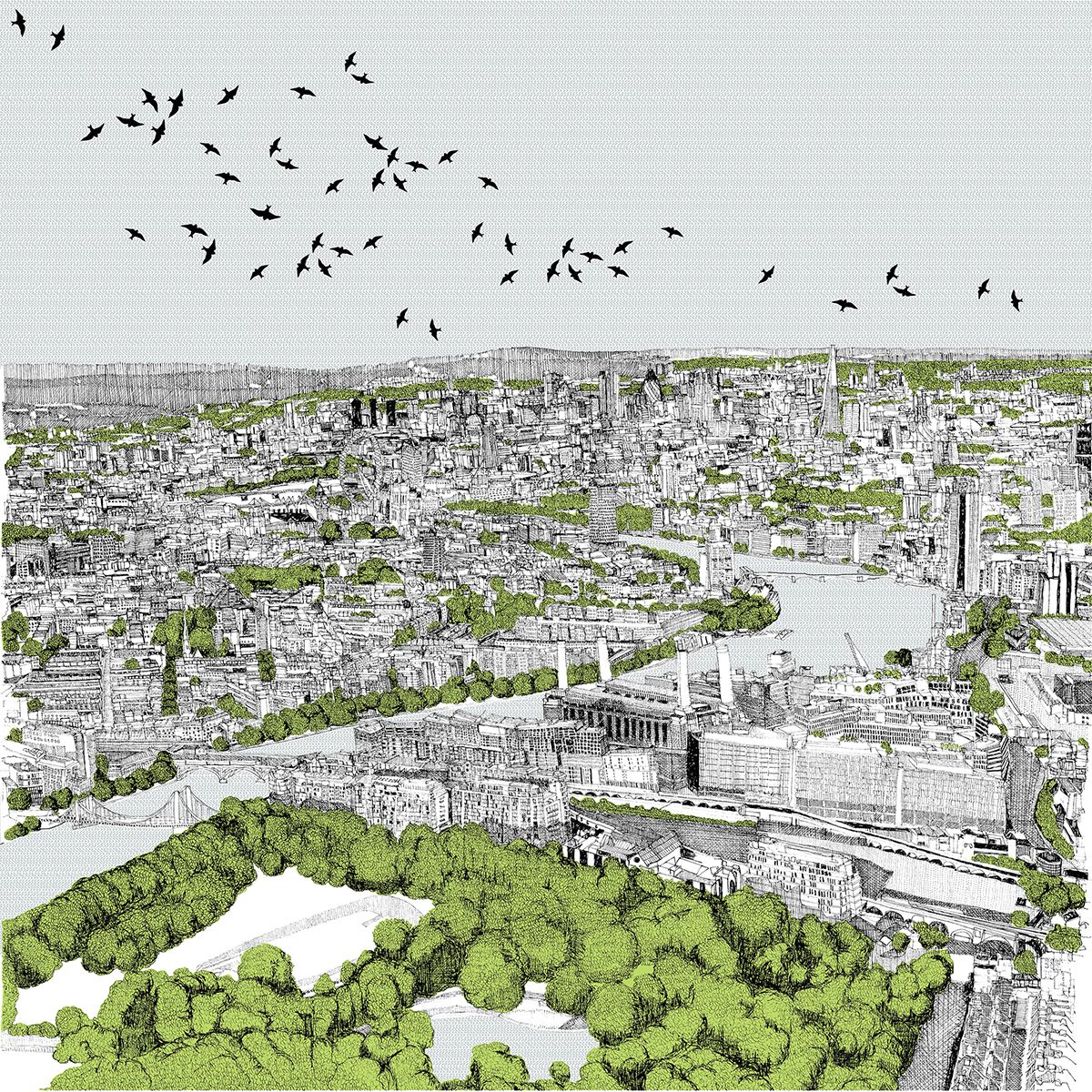

Recently I travelled along the Thames on a boat trip through the City of London and beyond, viewing one glass-clad monolith after another, each one bigger than the last, ending up staring at one glossy giant holding a vast 2 million square feet of office space. In his excellent book The Bird-friendly City Timothy Beatley describes how in North America, where they arrived early on, these glass-walled buildings kill wild birds, who, unable to see the glazing, fly into it, breaking their necks. In the US and Canada, where an estimated one billion wild birds die in this way every year, there are efforts to do something about it by, Beatley writes, using various types of fritted glass, changing the design, and adjusting the lighting. Some major cities, in particular Toronto, have been energised by local activists – in Canada the organisation is FLAP, the Fatal Light Awareness Program – and by public outcry to rewrite their building codes to try to prevent bird collisions with glass walls. But here in the UK, in the City of London? Not that I know of, and I have spent the last 20 years there working in conservation.

So The Bird-Friendly City is timely. The book describes encounters on a series of journeys from one continent and country to another, taking in Canada, the US, the UK, Singapore and Australia, talking to activists and finding out what they are doing to preserve our urban and migratory trans-urban birdlife. It provides the ideas, information and techniques we need to adopt to turn our cities into rich resources for Nature, improving them for us in the process. Why is this so essential? The UK government’s policy paper ‘A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment’ (2018) states:

“Spending time in the natural environment – as a resident or a visitor – improves our mental health and feelings of wellbeing. It can reduce stress, fatigue, anxiety and depression. It can help boost immune systems, encourage physical activity and may reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as asthma. It can combat loneliness and bind communities together.”

All this is well known. It motivated the inspired Victorian creation of superb public parks, and also the later Garden City movement that is even now driving the biophilic cities concept and transforming Singapore. And as so many have found out during lockdown, having a garden where they can sit or potter about tending the plants beats staring at a computer screen or looking out of a window at a high wall just across the way. Humans, like other animals, don’t do well in cages. But we invent prisons of the mind and the body, we put ourselves in them, and we lose sight of the real world outside. This book tells us how to reverse that and thrive in a world once again full of beautiful wild creatures, in cities that themselves are rewilded.