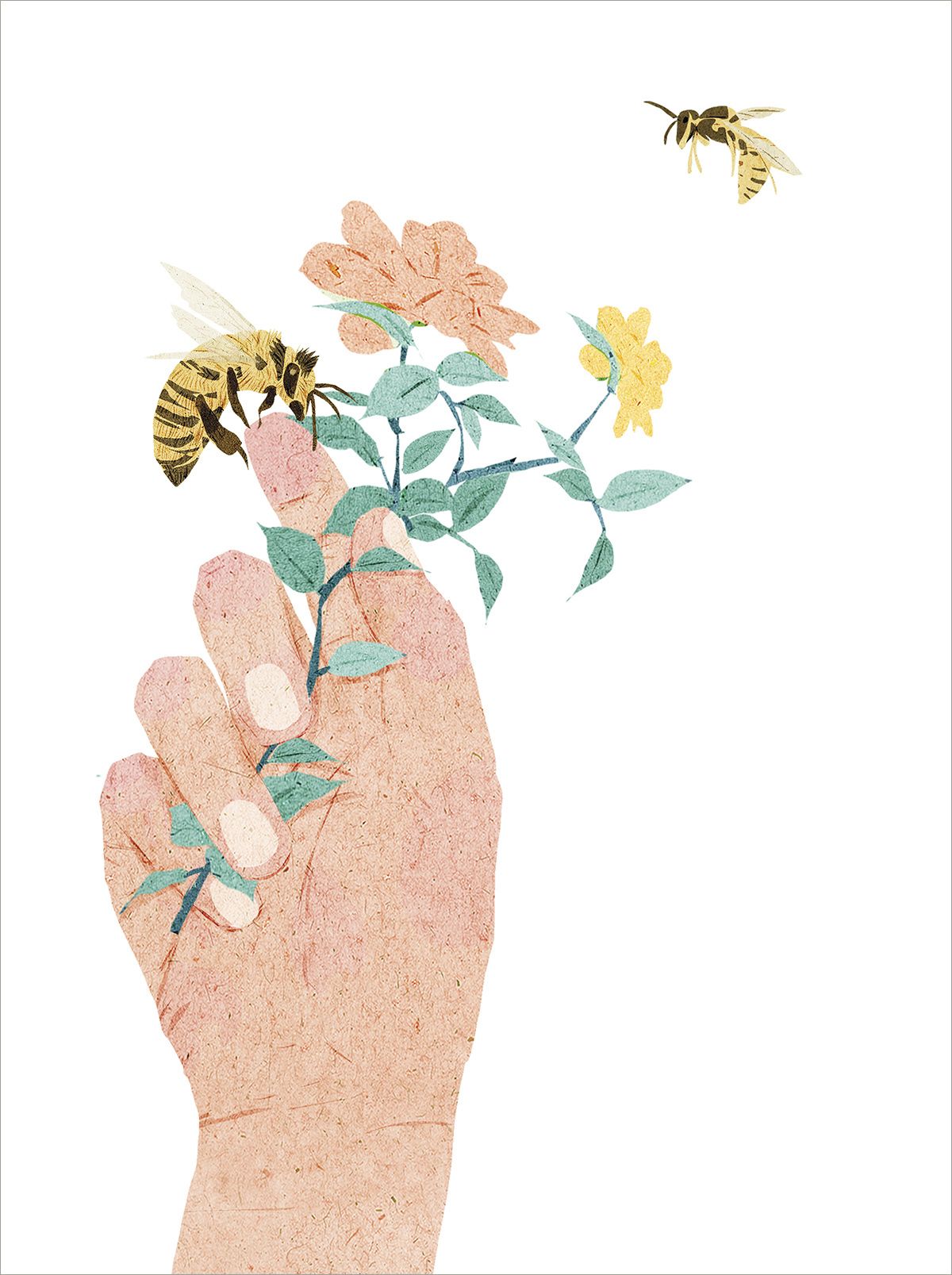

Wasps are welcome to disrupt my English classes. It’s happened more often this spring because of the requirement to keep windows open during the pandemic. I once resented the working time lost coaxing the little gatecrashers back out of the window, students screeching, swatting, pronouncing the death sentence. But six years ago something sticky-sweet on my finger from lunch presented me with an opportunity. I let the little creature linger on my open hand. “Watch out, sir! They can sting without dying, sir, not like bees!”

“Why would it sting me? In late summer they can be grumpy but this one’s fine. I think it’s a male because its abdomen’s quite slim.”

I’m among the desks, and a few students lean closer to see. “You know, without wasps, we’d be plagued by swarms of flies and midges and their rotting flesh everywhere. Wasps keep our ecosystems in balance. Without wasps, our food would be more expensive and less healthy because farmers would use more toxic spray to protect crops. There are 30,000 species of wasps and most are pollinators just like bees. There are even some beautiful flowers – orchids – that wouldn’t exist without wasps; they’ve evolved to look and smell like female wasps to trick males into pollinating them. Did you know there are honey wasps?”

Students further away stand up for a better view. Some move closer. “In Japan you can eat wasp larvae in fancy restaurants.” Disgusted cries. “There’s research going on into a wasp venom that might one day save your life, because it kills cancer cells without harming healthy cells.”

A minute ago we were in rows facing the front. Now we are in a circle.

In Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered, the economist E.F. Schumacher identifies the heart of the problem: we must decide what we want our economies to do for us, otherwise the relationship is easily inverted and economies enslave us. He devotes a whole chapter to education, writing, “If western civilisation is in a state of permanent crisis, it is not far-fetched to suggest that there may be something wrong with its education.” That crisis is today so glaring that many young people themselves are aware of the inadequacy of their own education system. Through the brilliant Teach The Future campaign some are demanding a curriculum review so that sustainability and climate change are taught “in all subject areas”. How would that look?

I’ve devoted much of the past two decades to communicating the reality of climate change in Leeds to all kinds of audiences, and I’ve learned that people have a great appetite for scientific explanations, but that knowledge on its own yields unpredictable responses. Depending on their prior value systems, people I’ve addressed have done everything from disrupting oil-sponsored art exhibitions to starting a climate denial blog. So education as if people and planet matter cannot rely on accurate information transfer alone. Indeed, if Schumacher is to be believed, we must address not just the content of the curriculum, but the purpose of life: “‘know-how’ is nothing by itself,” he writes; “it is a means without an end… the task of education” must be “first and foremost the transmission of ideas of value, of what to do with our lives.”

This question cannot be avoided. Every education system is necessarily an expression of – and therefore a teacher of – particular values. Ours grew out of the liberal tradition – ‘liberal’ because it aimed to free thinking from stifling religious dogma. Its curriculum, introducing the subjects we still learn, served the industrialising economy and nascent democracy, but made assumptions which are at the root of the ‘permanent crisis’ we now face: that Nature is a soulless mechanism to be moulded to human purposes; that its stock is effectively limitless; and that waste products are of no great significance.

It’s striking that the rise of neoliberalism – a new stifling dogma sanctifying the freedom of markets to generate profit – coincides roughly with destruction on a vast new scale, when 80% of all carbon has been emitted, and 60% of total animal populations have been lost. The education system has been refashioned to enshrine neoliberal values. Head teachers are trained as managers of learning factories which compete with each other for tomorrow’s children by proving that they are filling today’s up, like milk bottles on a conveyor belt, with the knowledge and skills to compete with each other in another, adult, market – for jobs.

Education as if people and planet matter must be based on very different, life-affirming values. Most teachers are motivated by a desire to care for children, so even now, in small ways, the system subverts itself covertly. In fact, I think this is what happens when a wasp disrupts my English class. Years after that first wasp lesson, a student gave me a thank-you card when she left school. She said that I had inspired her to participate in the Youth Strike for Climate and to study philosophy at university. To my astonishment, she cited not my many carefully planned lessons and assemblies around climate change, but “when you held the wasp.”

Pondering this has led me to the view that education’s purpose is best expressed not in terms of Schumacher’s abstract ideas of value, but in terms of concrete relationships. Answering his unavoidable question places people in relationships with each other and Nature, and these roles become the fundamental learning outcomes of the education system, feeding through into the economy and wider society. When I held the wasp, students’ relationships with wasps were transformed from something like antagonism to something more like allyship, and for at least one this set her on a new path.

There are several dimensions to the way this transformation takes place in the wasp lessons. Firstly, there are some facts which students have to make sense of. They are about how wasp and human interests align. The ecophilosopher Freya Mathews says, “if my identity is logically interconnected with the identity of other beings, then … my chances of self-realization depend on the existence of those beings… our interests converge.” Such information is necessary if people and planet both matter.

Secondly, an emotional dimension moves students from alarm towards empathy. In Life’s Philosophy, the philosopher of deep ecology Arne Naess argues for an education that takes “more account of feelings”, committing a chapter to cultivating “A feeling for all living beings”. An education system fit for the future today’s children face would produce emotionally literate young adults, more aware of deep motives in themselves and others, and experienced in conflict resolution.

But without a wasp present in the room, I doubt I’d have received that thank-you card, just as reading this essay you cannot ask some of the questions my students have asked over six years: “What’s it doing now?” “Can I hold it?” The presence of a living being is compelling, but factory education is addicted to smartboards, as though consciously acclimatising children for a semi-virtual life. What if children’s curricular entitlement was expressed in living encounters rather than topics? Outdoor classes would be a daily expectation. Visits by artists, asylum seekers and war veterans would be as commonplace as textbooks. Neoliberal education relies on divorcing school life from community life, but students of every age should be deeply involved in serving their local communities, for example by growing food, visiting old people and creating what Schumacher called intermediate technologies.

Finally, there is magic in the spontaneity of the wasp lesson. Naess links the central “feeling of being on a voyage of discovery” to slower, deeper learning within a spacious curriculum. Factory learning is ruled by the monstrous god Chronos, but wise education must revere the Greeks’ friendlier god of time, Kairos, whose educational incarnation is the teachable moment. This spring, when he has alighted incarnated as a wasp, I’ve dived into big questions: given that there is no known biological life anywhere else in the universe, how valuable is a wasp? Who gave you the idea that it’s OK to kill wasps? If “everyone” thinks so, does that make it true? (So the best of liberalism still contributes!) What kind of education system tells you about subjunctive clauses before you’re twelve, but never explains why we need wasps? What else is it not telling you?

Around 2,400 years ago the Taoist teacher Zhuang Zhou wrote, “I know the joy of the fishes in the river through my own joy as I go walking along the same river.” If we take young people for those walks, literal and figurative, the relationships they form with people and planet will empower them to work out the rest for themselves. A student recently said: “Sir, I think you’ve convinced my brain that wasps are OK, I just don’t know if I like this one.” Before I could respond, someone else piped up, “Sammy. He’s called Sammy. Bet you don’t want to kill him now!”

The essays to receive second and third prize, by Deepa Maturi and Guy Dauncey respectively, are available to read here. For more information about the prize, visit www.campus.dartington.org/schumachercollege-essay-comp-winner