The last two years saw the biggest economic disruptions in capitalism’s peacetime history as Covid-19 ripped through societies across the globe, and governments imposed lockdowns. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which we had become used to seeing grow year after year, suddenly looked less relevant than the immediate requirements of the public health emergency.

In practice, for so-called developed countries like Britain and the US, the relevance of GDP growth had already been thrown into question. For decades since the end of the second world war, steady increases in GDP across the developed world were matched by steady improvements in living standards. From the end of the 1940s right through to the 1970s real wages actually grew somewhat faster than GDP. The western capitalist economies became more equal as a result, with workers and the middle class taking a larger and larger slice of the pie. After the end of the 1970s, that relationship was flipped: economies tended to grow faster than real wages. Inequality increased markedly as the top fraction of society grabbed more and more of the developed economies’ total wealth. Even so, living standards in general improved over these three decades – though at a slower pace than before.

And then, after the 2008 global financial crisis, the link between GDP growth and improvements in living standards broke down. The developed economies have grown since then, often, as in the case of the UK, rather weakly. But real wages for working people have stagnated, whilst inequality has continued to worsen. The promise of GDP growth – that it would, over time, deliver improvements in most people’s living standards – no longer applies so consistently to the developed world.

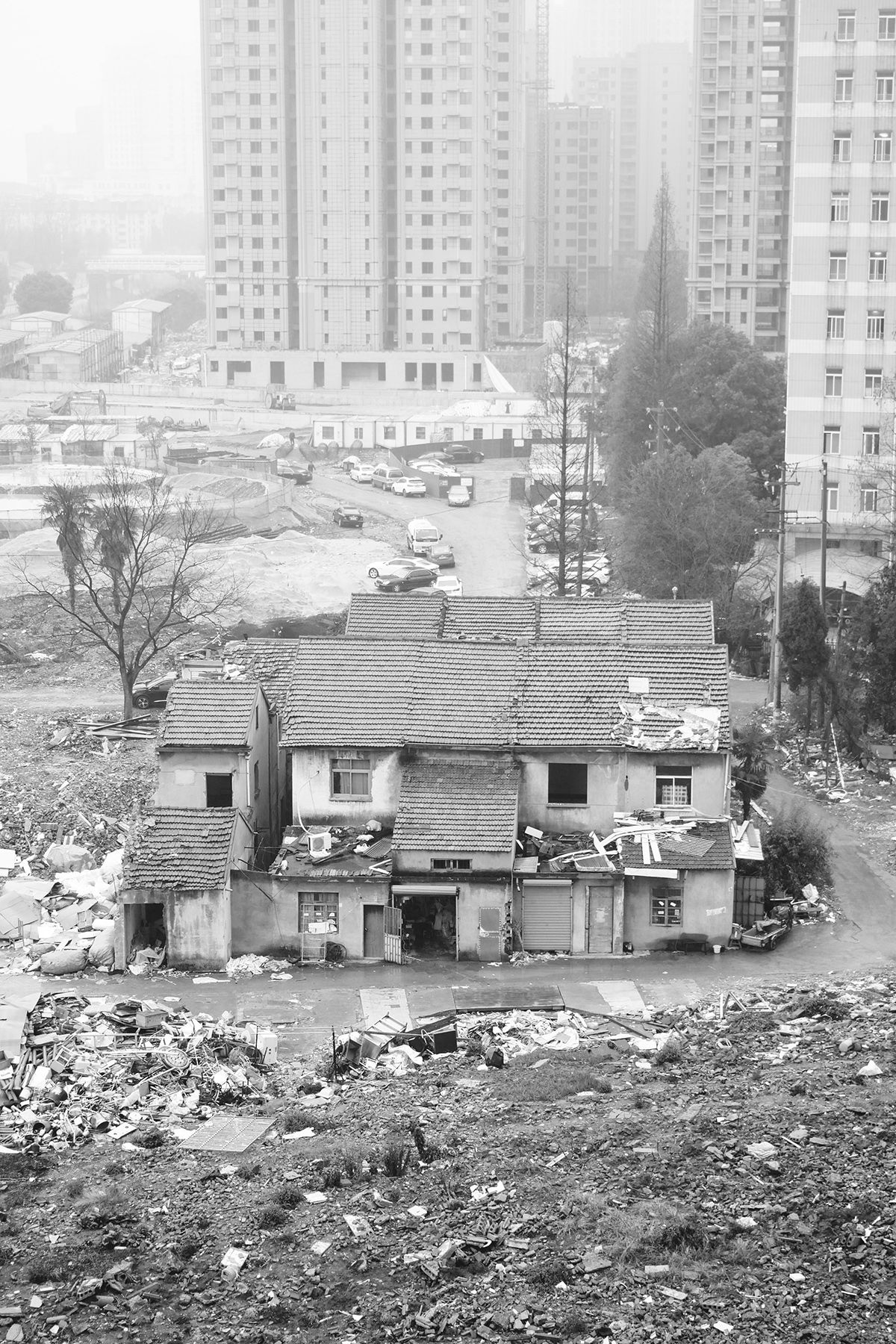

Outside of that charmed circle, the story has been different. China, notably, has seen the longest and most sustained boom in human history in the last four decades, transforming itself from a deeply impoverished country to the world’s second-largest – or, on some measures, largest – economy. Some 700 million people there have been lifted out of the worst forms of poverty. But unlike the west’s boom years, from the late 1940s to the 1970s, China’s exceptional growth has involved exceptional increases in inequality. China is today amongst the most unequal societies on the planet.

What ties the experiences, west and east, together is that widespread economic growth, of a kind that delivers improved standards of living for most people, has previously required immense consumption of the planet’s resources, particularly in the form of fossil fuel.

The claim by those pushing ‘green growth’ is that this relationship is not a necessary one: that it is possible to deliver growth, share its proceeds more equally, and break the link between growth and environmental damage. ‘Decoupling’ is the idea that as technology improves, it becomes more efficient, and as efficiency improves, the amount of resources needed to deliver each additional dollar or renminbi or pound of GDP will decline. It follows from this (it is claimed) that growth can continue, if it is of the right kind – green, efficient, and fairly distributed.

The difficulty, however, is that whilst technology certainly has improved over the last century, with (for example) each US$1 of global GDP produced requiring 1kg of CO2 emissions in 1979, but only 700g of CO2 emissions 30 years later, the rate of efficiency improvement is nothing like enough to keep us within the 1.5 degrees limit, if we assume that growth also continues. There is no plausible technology that will get us to the 3g of CO2 emissions per US$1 of GDP that ecologist Tim Jackson’s influential 2009 calculation suggests is needed. We should certainly seek out technological improvements. They just won’t be enough.

But if living standards are tied to growth, this might seem to create an insurmountable problem, particularly in an unequal world. It is one thing to suggest that living standards in comparatively rich countries might not improve, but where would that leave the 80% of the world’s people who live outside of them? Growth in some form for them remains an imperative if we are to address global inequality, and it is extremely hard to argue, from the perspective of the rich world, that the global south should not now be allowed to share in the much higher prosperity the north has – very unequally! – enjoyed for a century or more.

The solution appears in three parts: first, the introduction of low-carbon technologies on a global scale, as rapidly as possible. Second, the use of lower-carbon, resource-light technologies to drive growth in the global south, which remains important. And third, the redistribution of the world’s resources within the countries of the global north as the best available means to secure greater equality. With the promise of growth failing in the rich world, becoming no longer linked to rising living standards for most, this proposal is becoming less radical than it once appeared.