As you’re reading this, we’ll have come through another winter that, at the time of writing, feels anxiety-provoking and daunting. Demands on the UK health and social care system are higher than ever as we face whatever the latest evolution of Covid-19 brings (with Omicron the latest variant). Our energy and resources are severely depleted, and there is understandably high public expectation to get through the backlog of waiting lists. But let’s not pretend everyone wasn’t stretched before. This is a continuation of huge pressure, exhaustion, frustration and moral distress. Of course, there are inspiring stories too. What we see is people trying to do their best, stretched far beyond their limits.

Stepping back from the crisis, we hear conversations happening along the lines of “We can’t carry on like this” and “We need to do things differently.” In this feature, we’d like to share some thoughts on how healthcare services could be different.

We wonder who you are, reading this. Perhaps you are in a caring role (as a ‘health professional’ or perhaps an informal or unpaid carer), or maybe you are in receipt of care (as a ‘patient’, for example), or maybe both. We are all people, first and foremost. We invite you to notice and become aware of your reactions as you read this – your thoughts, and what comes up for you.

To start with, we encourage you to engage with an abstract exercise. Hear the following sentences in the voice of David Attenborough. Imagine him peering from a cupboard in a healthcare working environment, studying staff behaviour. What does he hear, and see?

“Here, these people are working in incredibly difficult circumstances, facing daily decisions that may link to life-and-death outcomes. As a result, they routinely experience anxiety and, to survive, they have developed strategies, which come in the form of ‘professional’ practices and procedures. These behaviours seem to form the basis for giving care, but are in fact defensive and self-serving.”

Of course, we are being provocative here. And also, we wish to invite you to consider some of the aspects of our behaviour that might be beneath our conscious awareness. Perhaps this might be the next season of Planet Earth – an uncomfortable mirror, reflecting back some of our habits and unexamined ways of doing things.

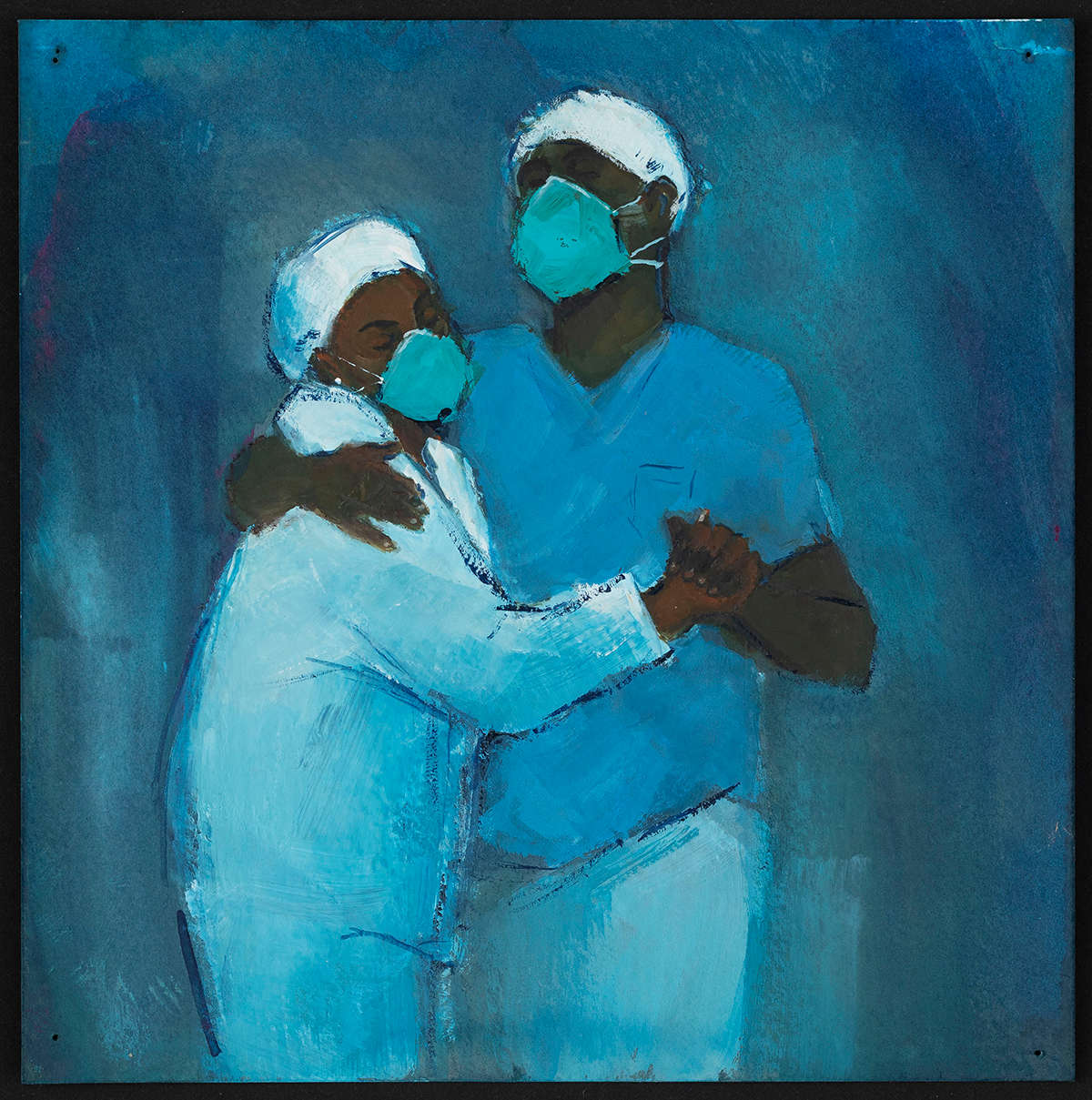

We believe that reconnecting with our humanity is not so much about a wagging finger of ‘must do better’, but more of a gentle reminder that, as people, we are necessarily imperfect, and vulnerable: we want to care, and we experience anxiety and pain. We want to feel safe, and it’s important to reflect and think carefully about the spectrum of our humanity. People trying to help people.

There is a necessary emotional cost to caring. Caring relieves pain and suffering when the person being cared for (the ‘patient’) can see an impact on the carer (the ‘health professional’) – it’s this connection that enables comfort. Empathy, a necessary ingredient of good care, has been described as getting into the water with someone without drowning. Whilst caring may not always involve experiences so overwhelming, that there will be no cost at all is as likely as walking through water without getting wet.

Compassionate care is what gives ‘professionals’ a sense of meaning, joy and satisfaction, and is, we believe, what ‘patients’ want. However, compassionate care can create anxiety and pain in the caregiver – this is a natural, realistic part of caring. So the challenge is, how do we respond constructively to this anxiety and pain?

There are helpful and unhelpful responses.

Our sense is that we have created a broad culture aimed at streamlining healthcare delivery that seems to reward and encourage unhelpful, formulaic ways of responding to anxiety, and we’d like to suggest some ways that could help us nudge towards more helpful ways of responding.

What do we mean by ‘unhelpful responses’?

At times people adopt practices and ways of working to avoid, numb, or get rid of the anxiety that arises naturally in the dynamic of caring. We believe that an unhelpful response is anything that contributes to ‘unthinking’, and this happens at both individual and institutional levels. It’s nearly 70 years since Isabel Menzies Lyth wrote about how organisations such as hospitals develop various ways to defend against the anxiety arising from caring and coming close to people in very vulnerable states. These ‘defences’ are perhaps not consciously designed to address anxiety, but rather they function to protect healthcare workers. Importantly, these defences create suboptimal conditions both for patient care and for workers to develop more healthy, more mature ways of responding.

What do defences look like?

Defences can come in various forms, such as aspects of the mechanical processes we use, such as having detailed protocols for everything (so that we don’t have to think); the detachment of ‘being professional’; constant busyness, and constant change; and labelling people with dehumanising terms. Clinical processes can encourage a focus on discrete tasks, and perhaps labelling people by their clinical condition, which can be managed through performing standardised protocols and rituals. These practices potentially make it more difficult to build up a holistic relationship with an individual person, and they also help to avoid the experience of strong feelings.

How do ‘unhelpful’ approaches get reinforced?

When we are aware of strong feelings in a colleague, we might pathologise and individualise. We interpret any expressions of anxiety as that individual colleague’s ‘problem’ – something that can be quickly and tidily swept away in offers of counselling, or wellbeing toolkit solutions, cleansing the rest of the environment. Our take is that this approach seeks to improve healthcare experiences by introducing yet more mechanistic solutions, rather than taking the time and care to make sense of our defences. And ironically, these further ‘solutions’ simply add yet more layers to our defences.

What does a ‘helpful’ response look like?

We believe it is far more helpful to notice the anxiety, name it, and feel free and safe to talk about it within a supportive relationship or context. It’s not about judging it as ‘bad’ or getting rid of it. We might call this ‘sitting with’ or ‘containing’ the anxiety.

This could be in more formalised support spaces like clinical supervision or various forms of reflective or listening spaces, or it could be more informal, just the day-to-day relational fabric of our work – team check-ins, having breaks with colleagues where just through our daily chatter we can express “Woah, I’ve had a really tough morning” and then feel not only heard, but really listened to. It could be anything that contributes to thinking about what we’re doing and why, how it might affect us, and how that in turn might influence the way we work.

How could we develop our capacity to respond in this helpful way?

Imagine if we could occasionally step back and take a curious observer position – discover our inner Attenborough, and share what we observe if we wish to. Our sense is that supportive relationships can enable each of us to feel a sense of safety to think out loud, to explore our clinical experiences in a way where we can be confident there will be no judgement or criticism. Also, we feel that supportive relationships can hold some challenge, some edge – being alongside, while also appreciating difference as a way of keeping thinking fresh and open.

Human relationships are best balanced between support and challenge, with support meeting our human needs, and challenge pushing us to admit that we are human, imperfect and capable of being wrong, and thus increasing our ability to think and grow. Both support and challenge need to be approached with empathy, and when done well may allow us to have difficult conversations and embrace critical thinking without descending into antagonism.

While many of us nod our heads at the idea of these more helpful responses, they are in fact very difficult to enact. It takes a big effort and commitment to move into a more helpful way of responding. This seems even more difficult in the current pandemic context of everyone being exhausted on multiple levels. Individuals cannot ‘just do’ this – it needs to be made easy to do these things at an organisational level. When we are exhausted, and where there are so many competing demands, it is easier to do something that seems to promise immediate relief, such as finding a generic proto-

col or toolkit off the shelf, when in fact these things might be more part of the problem. Our sense is that what can be most stressful is navigating the convoluted processes that we have put in place. Paradoxically, the processes put in place to block out anxiety can in fact cause more anxiety.

And what about power and hierarchy?

We talk about compassionate health care, person-centred care, shared decision-making, and collaborative care, and yet we also identify ‘patients’ and ‘professionals’, creating the potential for tricky power dynamics, and a dominant narrative that is often owned and led by the professionals. Hierarchy exists too amongst healthcare professionals, with power and status being defined through different bandings and pay scales. We talk about working in a multidisciplinary way, yet we don’t typically talk about hierarchy. Power is all around us and can get in the way of honest conversations – who speaks first? How are decisions made? None of this is intrinsically bad, but our sense is that it is useful to bring some of these power and relational dynamics into our conversations. As a reflective exercise right now, you might consider your own working conditions, and ask, “Are there things I would do differently if I could?” If the answer is yes, what are the powers preventing you from doing so?

It might seem so obvious that it doesn’t need saying, and yet it might be so obvious that it is often forgotten: the ‘us and them’ of professional and patient are socially constructed, and, as psychiatrist Irvin Yalom suggests, we may each be better described as ‘fellow travellers’.

Embracing our humanity

We know really that vulnerability, pain and ultimately death are part of our shared human experience. Perhaps we have overplayed and industrialised the role of ‘health care’ and the machinery of health care. Perhaps we have lost our connection to our common humanity.

There is no anxiety-free way to care for another person. Our aspiration is to embrace the anxiety and know that support is available. The problem is that when we feel anxiety we often then see ourselves as imposters, and not good enough. However, as Neil Gaiman puts it, “Maybe there weren’t any grown-ups, only people who had worked hard and also got lucky and were slightly out of their depth, all of us doing the best job we could, which is all we can really hope for.” Doing the best job we can, we would argue, is not about avoiding our anxiety, but acknowledging it, talking about it, understanding it and learning from it.

To embrace our humanity is to embrace our imperfections and vulnerabilities. We are wondrously dynamic, caring creatures. Uncertainty and anxiety are intrinsic to health care, and instead of creating multiple layers of problematic defences against this, we need to weave helpful ways of facing and containing this anxiety – space for honest exploration of some of the complexities; space where we can admit we’re scared, we don’t have all the answers, but we’re trying to do our best, and let’s ask how we can help each other out.

We will be discussing this article at the Resurgence Readers' Group meeting on 23 May 2022. Book a free space at http://www.resurgenceevents.org/events