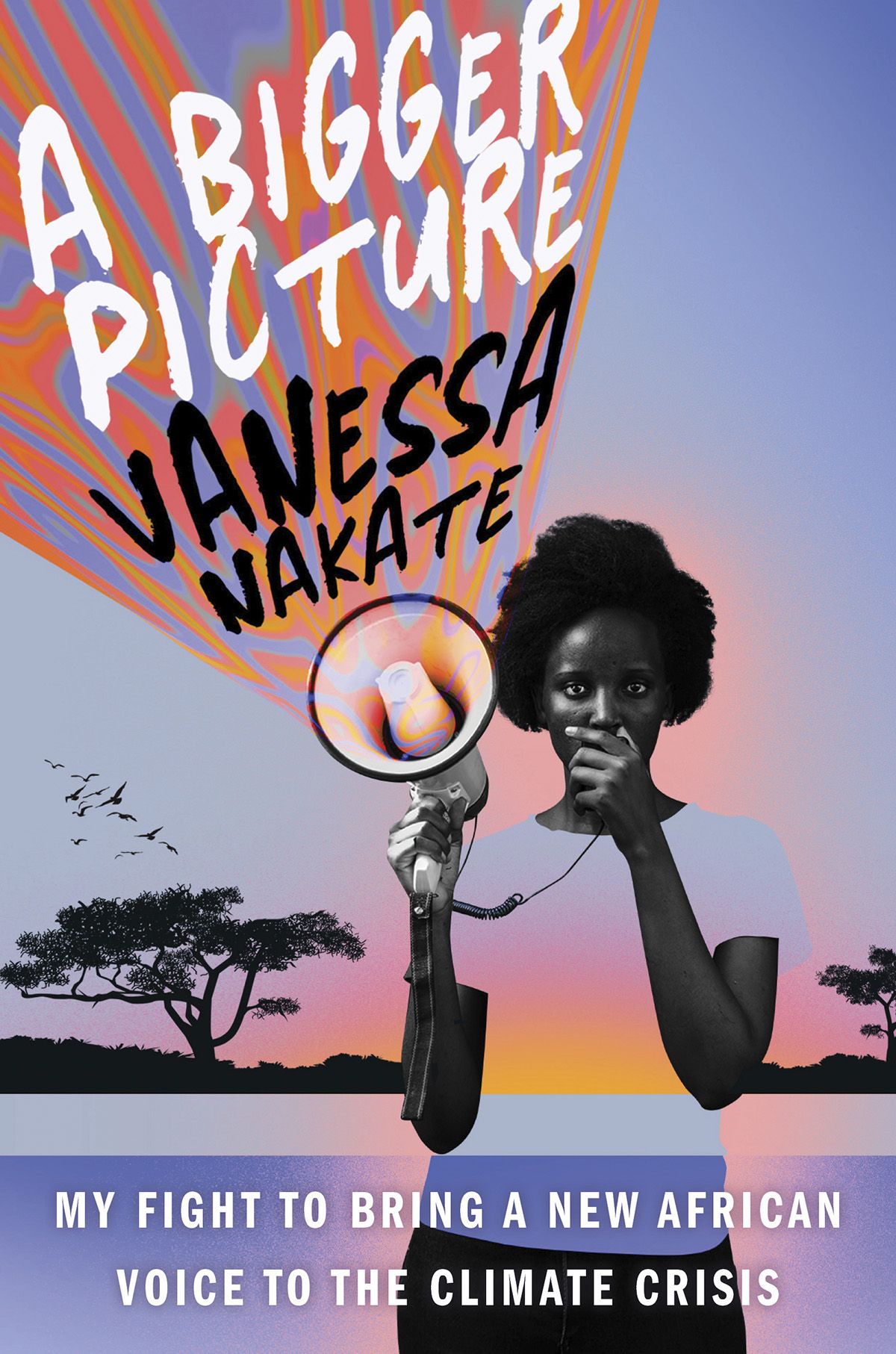

Confronting the unjust power structures that leave those on the frontlines of the climate crisis vulnerable and voiceless, Vanessa Nakate has crafted a memoir that goes beyond the personal. She makes a spirited, engaging narrator, and her voice is all the more powerful for it; when the lives of those around you are at immediate risk, you don’t hold back. We know that climate justice is linked to social justice, and A Bigger Picture illustrates in sobering detail just how this plays out.

The Everest-like challenges this young Ugandan environmental activist has faced on her journey to bring climate justice to Africa are shared by many in her country and across Africa. Societal pressures rooted in gender are inescapable: well-brought-up young women are meant to be “demure and respectful”, she writes. Stand on the street with a placard, and you might be accused of being a prostitute.

In Uganda, strikes are illegal – you could be arrested and, worst-case scenario, disappear. You’d be confronted by a lack of funding, indifference from your fellow citizens, and racism abroad – in Davos, at the World Economic Forum, Nakate was cropped out of an Associated Press photo, in which she, the lone Black African climate activist, posed alongside four white activists. (“Does that mean I have no value as an activist or that the people of Africa don’t have any value at all?” she asked, in an impassioned video that went viral.)

Nakate highlights the challenges activists from African countries face in getting accreditation to conferences and in securing visas or funding visits to speak abroad, and a lack of opportunities to speak once there. The voices of Black activists often go unheard at home, another facet of colonialism’s toxic legacy. “There’s still a form of white supremacy that operates in Uganda, and elsewhere I’m sure, because as Africans we have been told to think that white people are above us…”

All of this has spurred Nakate on to amplify the voices of her fellow African activists, among them Ugandans Hilda Flavia Nakabuye and Leah Namugerwa, Zambian Veronica Mulenga, Kenya’s Elizabeth Wathuti and Nigeria’s Adenike Titilope Oladosu.

The risks to African ecosystems that fuel her activism are many: flooding, famine-inducing drought and locust plagues that drive migration and leave people in a state of desperation and hopelessness; oil pipelines that lead to the resettlement of families and a loss of wildlife habitat; and the deforestation of the Congo River Basin’s rainforest, the ‘second lungs of the Earth’.

The picture Nakate paints is bleak, but she is not without hope – the activist in her strives to find solutions and generate support. She points to grassroots projects, some of which she has helped to implement: the provision of solar panels for family homes, efficient cooking stoves in schools to reduce the need for firewood and coal, and the growing of fruit trees and successful tree planting. Green jobs too, she says, are crucial if Africans across the continent are to move away from a reliance on fossil fuels.

The education of girls, she emphasises, is vital to addressing the crisis. “We need women in the rooms where decisions are being made that affect the climate. Educating girls brings them into those rooms, and expands the number and approaches of possible decision-makers and solutions.” Let’s hope Nakate’s brand of common sense spreads, and fast.