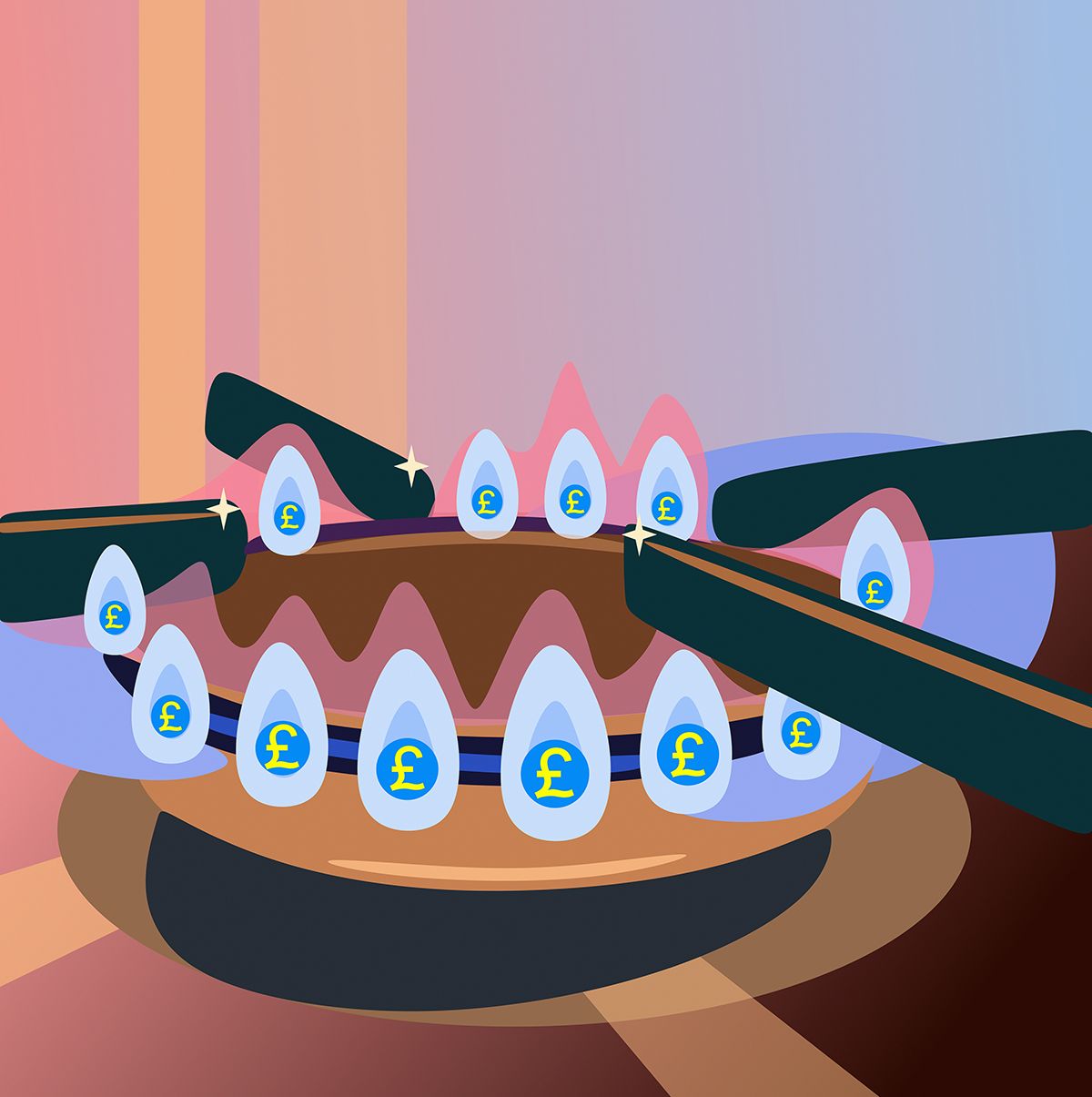

The UK government faces a revolt by working people over living standards, of which inflated fuel bills, exacerbated by wasteful, fossil-fuel-dependent energy systems, are a key driver. Rail workers’ strikes have won widespread public support. Nurses, teachers and other public sector workers, whose real wages have been cut by inflation, might take action too. And millions more people, including those with precarious work or no work, face energy bills they simply will not be able to pay. The movement on living standards can and must be linked to demands for energy-saving measures such as home insulation. The words 'climate justice is social justice' can and must become actions.

Average energy bills for households on standard tariffs leapt up to £1,971 per year (from £1,277) when the price cap was lifted in April this year. This coming October, bills could well rise above £3,000. A huge chunk of this money is paid by households for heat energy produced from fossil fuels that is wasted by poor insulation. A national programme of home insulation is needed.

Millions of those unpayable October bills could be cut by nearly one third if buildings were upgraded to a widely recognised energy performance standard, according to climate change think tank E3G. At least 15.3 million households with an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) of D or below will pay an “inefficiency penalty” of £916 per year or more, E3G estimates. If they were upgraded to EPC C or better, in aggregate they would save £10.6 billion.

The benefits cannot be measured in money alone. There are children whose lives and development are being damaged by this obscene waste, in as many as 2.5 million of the estimated 6.3 million UK households currently in fuel poverty. And burning fossil fuels – mainly gas, either in power stations to produce electricity or in household boilers – is adding to the climate crisis that produced record, life-threatening heatwaves in India in May this year. The faster we minimise waste and move to an integrated energy system based mainly on renewables and heat pumps, the better.

This year’s galloping fuel prices have thrown a harsh light on the fundamental injustice and unsustainability of fossil-fuel-based energy systems. Gas, oil and coal prices started rising on world markets last year as economies recovered from the pandemic. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed them further and caused a global food price shock. The war, and sanctions on Russia by western powers, could keep fossil fuel prices high for years.

The government’s “energy security strategy” announced on 7 April this year – which gave a climate-trashing green light to new oil and gas production in the North Sea – does next to nothing on energy efficiency. It rehashed already inadequate support schemes for homeowners. Hints dropped by government ministers on 16 June about more money were empty PR: they are talking about redistributing cash already committed to public-sector buildings.

The actual rate of energy efficiency installation has fallen by 90% over the last decade. The energy security strategy includes a target of 600,000 heat pump installations per year by 2030 – compared to the 19 million that are needed. The installation rate so far is a dismal 10,000 per year. Urban planners and decarbonisation researchers have been advising the government for years to get on with retrofitting homes. The government’s own business and industry department told it so in a big report in 2018; the same Climate Change Committee urged action in 2020.

Campaign groups have already recognised the potential for linking the fight over the cost of living with the fight for serious action to tackle climate change. Climate activists from Friends of the Earth and Extinction Rebellion joined rail workers’ picket lines, pointing out that well-funded public transport not only benefits those who work on it, but also is essential to decarbonising transport and reducing fossil-fuel-guzzling traffic.

The movement can learn a lesson from the ‘Yellow Vests’ protests in France in 2018. These were triggered by the inclusion in the budget of a carbon tax on final consumers that led to the price of diesel going up. The ‘Yellow Vests’ rightly saw this as essentially a regressive tax, inspired by the Macron government’s neoliberal economic strategy. Although most of the movement agreed that action on climate was needed, they saw no reason why French working people should pay for it while elite privilege was protected. They were concerned about the alienation of the vast majority of French society from the political process. They coined the phrase “The elites talk about the end of the world, but we worry about the end of the month.” Less well known was the slogan that responded to it: “End of the world, end of the month, same fight!” Jubilee Climate and other campaign groups are now mobilising around that principle.

If we don’t confront the crisis of energy bills with a ‘same fight!’ approach, then the populist right will step in, attacking the government’s ‘net zero’ strategy with the false claim that decarbonisation will damage family incomes.

It is important, too, to start conversations in communities about how the energy system works; about movements in the past that have demanded energy as a right and/or a public service, rather than as a commodity; and about how we can become actors in getting the heat, light and electricity we need, rather than being passive ‘consumers’.

Practical steps to strengthen the movement could include:

• The ‘Don’t Pay’ campaign, launched at the TUC demonstration about the cost of living on 18 June. The group, recalling mass non-payment of the poll tax in 1988–89, aims to bring together one million supporters to demand “a reduction of bills to an affordable level”, and to build towards cancelling direct debits from 1 October “if we are ignored”.

• Organising to protect families who cannot pay their fuel bills, as Fuel Poverty Action and the local groups it supports do.

• Linking climate protest with trade union action for a just transition. A good starting point is the Leeds Trades Union Council’s campaign for retrofit and heat pumps, as an alternative to proposals, backed by the fossil fuel industries, to turn gas networks over to hydrogen.

• Interacting with local councils that have declared a climate emergency but failed to act on it. Climate Emergency Manchester provides a great example of how to keep on a council’s back and dispute its greenwash, and building links with co-ops and community energy projects, such as Carbon Co-op Manchester and South East London Community Energy.