The arrival of Covid changed my relationship with walking. Unable to live ‘normally’ during lockdown, I turned to daily walks to broaden my horizons. And with the focus of life narrowed down to my local area, I found it easy to imagine that those friendly-looking footpath signs were speaking to me and my desire to get out and explore the countryside. So I was intrigued to discover that some of our footpaths are part of a pattern of countryside trails that have less to do with getting fresh air and exercise than with how people and communities lived and made connections with each another in the past. “Many have been created by use over centuries,” says Jack Cornish, the Ramblers’ head of paths. “They’ve been used by people for everyday travel to work, to the fields and the pub. They tell a story about how our communities have evolved and are the oldest part of our collective heri-tage still used for their original purpose.”

There are hints of this story in some of their names: bodies would be carried from remote rural areas to cemeteries along coffin roads, a mass path would lead to church, livestock would be driven to market along drovers’ roads, and goods were transported along packhorse routes. Different parts of the country have their own paths: smugglers’ lanes in Cornwall, miners’ tracks in Yorkshire, and stalkers’ trails in Scotland.

Some go back as far as 5000 BCE. The Ridgeway, thought to be Britain’s oldest road, stretches from Avebury in Wiltshire to Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire. When the Romans invaded in 43 CE they created a network of roads, such as the Fosse Way linking Exeter to Lincoln. After they left, around 410 CE, the Anglo-Saxons established villages and created routes to connect them. And in the 12th century the Cistercians established a network of trails, now delightfully called Monks’ Trods. It wasn’t until the 20th century that national walking trails such as the Pennine Way appeared, and in 1968 the Waterways Act allowed public access to all the canals.

There are four main public rights of way in England and Wales: footpaths (for walkers), bridleways (also open to horse-riders and cyclists), restricted byways (which also allow for all other non-mechanically propelled vehicles), and byways (theoretically open to all traffic). Other routes include permissive paths, where the landowner has granted access, and green lanes, which are ancient pathways that often follow the contours of the landscape. There is also a limited right to roam over some mountains, moors, heaths and areas of downland.

There are 140,000 miles of legally recorded public rights of way in England and Wales, and the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act required authorities to keep a record of all those in their area, known as the definitive map. But many historical paths were not recorded. Until recently, under the rules of the 2000 Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act, there was a requirement for them to be added by 1 January 2026, or they would be lost for ever, and in 2020 the Ramblers launched their Don’t Lose Your Way campaign. Since then, with volunteer help, they have discovered over 49,000 miles of lost paths, and the deadline has been lifted. But, according to Cornish, who is also the campaign’s programme manager, their work is not over: “Once added to the definitive map, paths are protected under the law for people to use and enjoy for ever. If successfully claimed, the missing paths will have the potential to increase the path network in England and Wales by up to a third,” he says, adding: “It’s great news that the government has announced they will scrap the cut-off date, but we still need them to get the repeal successfully through parliament.”

Organisations such as the Ramblers and the Open Spaces Society have protected Britain’s public rights of way for decades. But a different way of connecting communities has been dreamt up by Dan Raven-Ellison, who, in 2020, started the Slow Ways project (Slow But Sure, Resurgence & Ecologist, January/February 2021). “It’s founded on the principle that people should be able to walk reasonably directly, safely and enjoyably between any two neighbouring villages, towns or cities,” explains Raven-Ellison. “The official maps are a fabulous resource, but they are just maps of paths. They show you where you can go, but they don’t tell you good ways to go. To answer that you need local knowledge.

“During the first lockdown, volunteers suggested ways to walk between every town, city and national park in the country, resulting in over 8,000 routes stretching over more than 120,000km. Our current challenge is to walk and review them all to make sure they’re good enough to be included. Volunteers have shared 70,000km of reviews, but we want every route to be checked by at least three people, so we’ve at least 290,000km more to do!” he says. “The prize is having a national walking network that will bring joy to people’s lives, connect communities and help tackle the climate emergency.”

The Slow Ways network includes Scotland but not Northern Ireland, where the rules are slightly different and they have only three types of legally protected public rights of way: footpaths, bridleways and carriageways. In Scotland there is no legal obligation for local authorities to record public rights of way at all, but they have a National Catalogue of Rights of Way compiled by the Scottish Rights of Way & Access Society (ScotWays) in partnership with Scottish Natural Heritage and local authorities. Crucially, they also have the right to roam over most of the country – something Guy Shrubsole, the author of Who Owns England? and Nick Hayes, who wrote The Book of Trespass, have been campaigning for in England and Wales.

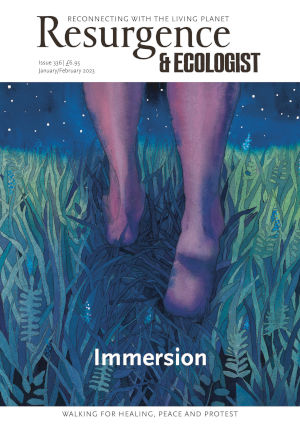

The access movement began with the Kinder Scout trespass in 1932, when 400 walkers took to a moorland plateau in what is now the Peak District, clashing with gamekeepers sent to remove them. This led to the creation of our National Parks in 1949. And the tradition continues: last year, protesters entered the estate of Lord Benyon, parliamentary under-secretary of state at Defra, demanding better access to the countryside for everyone. The effects of this and other recent acts of mass trespass are yet to be seen. But whether we choose to take this approach or keep to the official pathways, exploring the countryside along these routes connects us not only with Nature, enabling immersion, but also to our history and the travellers who trod these paths before us, inviting us to follow, literally, in the footsteps of our ancestors.

For information about public rights of way in your area, consult your local authority. Find out about the Don’t Lose Your Way campaign. Find out about the Slow Ways project