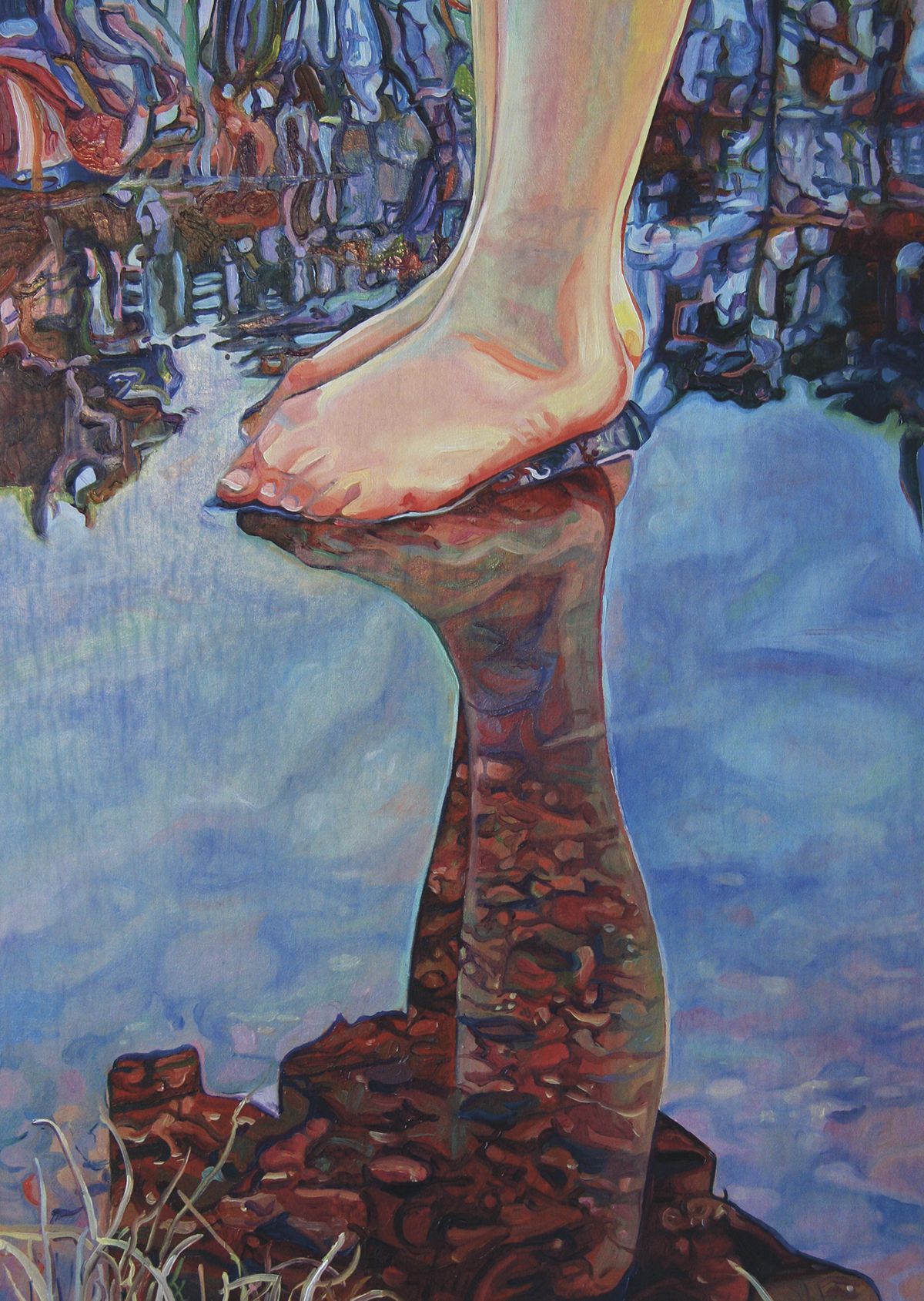

Psychologists call it ’soft fascination’ – the ability moving water has to capture our attention in such a way that we can stare at it for hours, making journeys of a thousand miles or a million years without ever taking a step. There’s something about time by, on, or in a river that takes us out of ourselves: that desire to just sit and watch the water flowing, to let the light it reflects gently cleanse our minds. Dancing flames, scudding clouds, fluttering leaves and ocean waves possess something of this quality too, but for me rivers offer the softest fascination – I think, perhaps, because the water is self-evidently on a journey of its own. A river is where water, that most familiar and remarkable of substances, is most alive. It feels good to live alongside it, but more than that, it does us good.

Science has now caught up with what Nature lovers have always known – that time in green space is beneficial for our physical, mental and emotional wellbeing. More recent research strongly suggests that the benefits of access to watery places are even greater. People living within one kilometre of so-called ‘blue space’ are healthier than average, even allowing for different socio-economic circumstances. Studies in urban areas by the pan-European BlueHealth initiative show that both health and social cohesion improve when a community gains access to blue space. This shouldn’t surprise anyone. Humans have always favoured riverside locations for practical purposes – water is, after all, essential for drinking, for washing, for harvesting and growing food, for transit and transport, and as a begetter of political and energetic power. But its significance is metaphysical too, and rituals of immersion, libation, communion, celebration, promise, thanksgiving, healing, pilgrimage and purification run through almost all world religions. We dip, pour, sip, raise a toast, deposit offerings, bathe, dose, follow, wash and commit to water from the beginning of life to the end.

We’ve forgotten that access to natural running water is a sacred privilege, and part of that forgetting, is, I believe, because we have become divorced from it. In England, ‘zombie rivers’ are brought to us through taps and flow away in a chemicalised flush. We are largely spared cholera, dysentery and typhoid and a host of other waterborne diseases, but we have lost something in the process. We have forgotten where water comes from and where it goes. We have forgotten that water is sacrosanct.

In England we currently only have secure and uncontested right of access to 3% of rivers. On the rest, if you’ve not been granted permission by individual landowners there’s every chance someone will challenge your right to be there. It means that on almost every swim or paddle, when I encounter a person on the bank, my first thought isn’t, here’s someone else who loves this place, but, are they going to give me a hard time? That’s not good for anyone’s health. It is notable that the rivers with the most proactive, vocal and effective guardians are those where the water is accessible. The Wharfe, where campaigners have highlighted sewage pollution, the Wye, where agricultural slurry is killing the river, and the Cam, where in 2021 a group of local people who have had the opportunity to know and love this celebrated chalk river gathered to formally declare it legal rights: this kind of active love is unambiguously the result of access.

Despite the demonstrable benefits of spending time by the water, there’s a danger in treating Nature as a therapeutic resource. The river is good for us, but are we good for the river? This is an important question. Being good for the river means loving it in return. Collectively, humanity is currently not good to rivers: agricultural pollution (silt, pesticides, and excess nutrients leading to algal blooms) and sewage (plastics, nutrients and pathogens) are destroying them, and in our longing to be beside them there’s also the potential for physical damage to banks and riverbeds and disturbance to wildlife, as well as more insidious threats: the eco-toxic components of sunscreens, cosmetics and insect repellents, and the transfer of invasive species from one water body to another. So how can we make our presence a benign or beneficial one?

Well, there are obvious practical things we can do minimise our negative impacts: buy organic food and clothing, join a conservation organisation, lobby politicians for improved regulation of water quality and abstraction. And when we visit a river, we can also leave a positive trace by collecting litter or contributing to local campaigns or citizen science efforts to record wildlife sightings or pollution events. But we can do better than that. Through the metaphysical interrelationship of ‘soft fascination’ our love of the river becomes reciprocal. Our thoughts become expansive and inclusive as they flow with the water, deepening and eddying as does the river. We love the river, and the river loves us back. In the words of the Buddhist monk and eco-philosopher Thich Nhat Hanh, “we inter-are”. In this way, we can be good for one another.