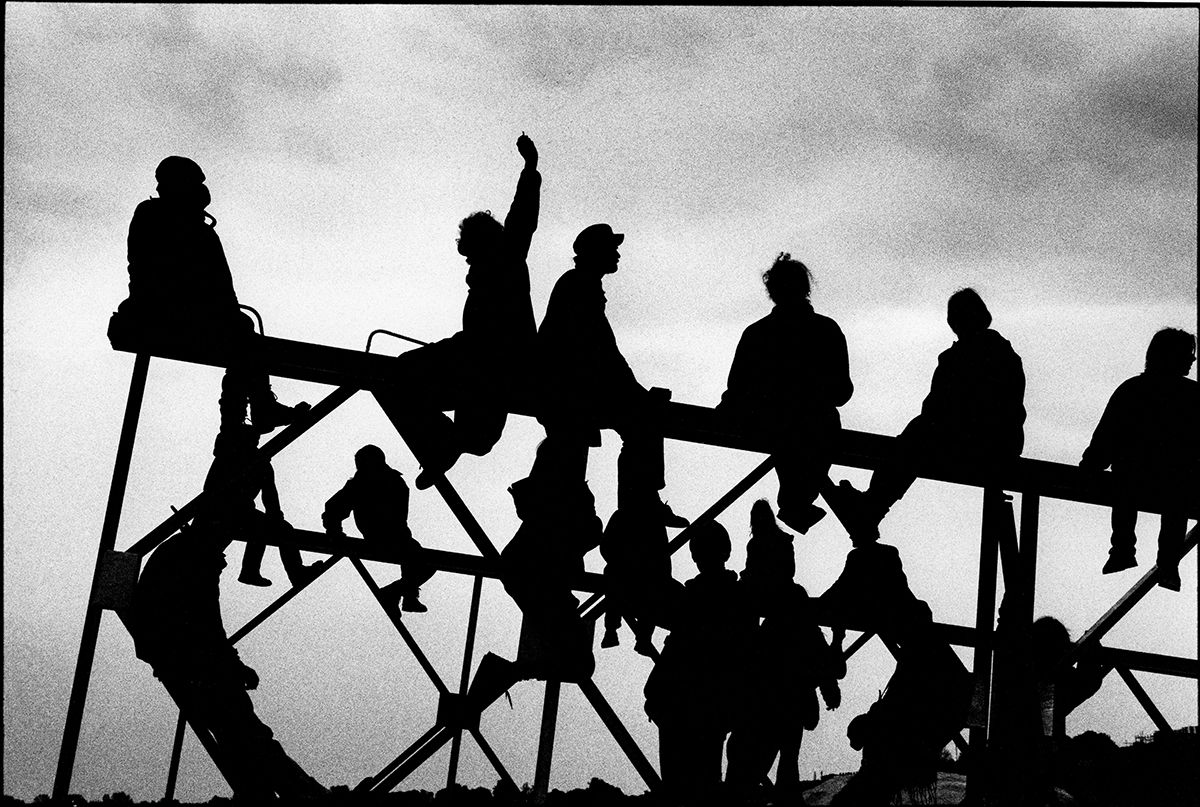

A poem in The Ballad of Yellow Wednesday – my recent collection of poetry, published by Valley Press 30 years after the anti-roads protests at Twyford Down in Hampshire – describes what happened one night in 1993 on the banks of the River Itchen at the foot of the hill:

Toll

Saturday 22 May 1993

We pulled away the razor wire, pushed the fencing

flat, and we were in, then up, then on, all

two hundred of us, swarming above the valley

on the girders of their Bailey bridge.

All night we banged out rhythms with whatever tools

we had to hand: we made the metal sing,

brought forth a chime, a knell, a toll,

a resounding reverberation, a peal;

with measured strokes we struck the bracing

frames as if they’d been cast from bell metal.

From beneath our huddled silhouettes, all

across the landscape you could hear the bridge

finding the colour of its voice, rejoicing.

The toll rings out across the valley still.

The Department of Transport was attempting to build a Bailey bridge enabling large earth-movers to enter the construction site of the ‘missing link’ of the M3 motorway, which was being bulldozed through this ‘theoretically protected’ chalk downland, a few miles from where I grew up. That night, the Department of Transport’s plans – code-named ‘Operation Market Garden’ – were disrupted by ‘Operation Greenfly’, our counter-action as protesters. But why did I need to translate our protest into poetry?

One of the principal values of poetry is the communicative power of the image. In ‘Toll’, I was seeking to encapsulate the cacophony of protest in a sonnet – a poetic form whose name derives from the Italian sonetto, meaning ‘a little sound or song’ – by using the visual and aural image of the bridge. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard writes: “Through the brilliance of an image, the distant past resounds with echoes, and it is hard to know at what depth these echoes will reverberate and die away.” To truly communicate and show what happened at Twyford Down, to let those events reverberate, I needed to do this through poetry.

It was clear to me, as I began to write my collection, that Yellow Wednesday was a pivotal moment. This was Wednesday 9 December 1992, when – after years of public inquiries, legal action and campaigning – dozens of security guards wearing fluorescent yellow jackets moved onto the Down, followed by bulldozers, to begin the main phase of construction work. They were met with resistance by the Dongas Tribe, a small group of young people camped on the hill, who took their name from the ancient trackways on which they were living. This key narrative episode involving a battle and a tribe demanded to be written as a ballad. Searching for models, I found Lorca’s Ballad of the Spanish Civil Guard, with its astonishingly appropriate elements: the oppressive forces of the state, festivities, the moon. I was off and running. I created a line-by-line version of Lorca’s ballad, spinning off from his original Spanish, incorporating press reports of Yellow Wednesday, first-hand accounts by those present, and of course, my own memories.

Some of my other poems respond to contemporaneous photos, many by Alex MacNaughton, in a dialogue known as ekphrasis. The late poet Ciaran Carson suggested that my collection as a whole is “an ekphrasis of landscape”: “The landscape speaks out to you and you speak for it; the landscape speaks through you.” He further remarked that the poems are “grounded in various languages and registers: phonological, etymological, archaeological, geological, legal …” Carson felt that the phrase “a shingle of cameos” in the opening poem, Chalk, with Flints, was the key to understanding the mix of components of my book. I had arrived at this image by looking at photos of chalk under a microscope. Its coccoliths, the round calcareous plates that once formed the exoskeletons of microscopic plankton, reminded me of cameo brooches. Thus an image derived from the minuscule, once-living constituents of chalk had come to stand for a whole collection of poetry about the destruction of a massive chalk hill.

The legal language Carson refers to is taken from the material of the court proceedings – speeches, excerpts from judgments – as we were prosecuted for defying an injunction forbidding us from walking on Twyford Down. A corona of sonnets titled Holloway Letters (The Martyr’s Crown) draws on my memories, prison diary, and the several hundred letters fellow campaigner Becca Lush and I received whilst in Holloway Prison. The thirteen sonnets mirror the thirteen days of our incarceration; their small square forms echo both the letters and the prison cells.

Does poetry, then, have a role to play as witness to our impact on the Earth? Poet Laureate Simon Armitage certainly believes so. Judging the inaugural 2020 Laurel Prize, he commented: “Contemporary poetry is bearing witness to the fragile state of the planet and the importance of engaging with Nature through detailed observation and considered language.”

Neil Astley goes further. In his 2007 anthology, Earth Shattering: Ecopoems, he extolled the potential galvanising function of poetry: “As the world’s politicians and corporations orchestrate our headlong rush towards Eco-Armageddon, poetry may seem like a hopeless gesture. But its power is in the detail, in the force of each individual poem, in every poem’s effect on every reader. And anyone whose resolve is stirred will strengthen the collective call for change.”

Kate Simpson echoes this sentiment in the introduction to her very timely 2021 anthology, Out of Time: Poetry from the Climate Emergency, arguing that the speaker of a poem “is capable of pulling readers into an imagined space and rallying a cardinal, immediate response”.

In 2001 I took the decision to stop being an activist in order to focus on writing poetry because I had a visceral need to create something rather than constantly trying to stop things being destroyed. And poetry requires time: a poem can only be an effective instrument if you let it disclose itself. Then, by banging out the rhythms with whatever tools we have to hand, through what poet David Morley has called “this small singing”, we might, with luck, find the colour of our voice. If we are very lucky indeed, our poetic images might even occasionally reverberate and overcome time.