At the time of writing, Lula has narrowly won the first round of the presidential elections in Brazil, in part on a campaign platform committing to protect the Amazon rainforest after the untold destruction wrought during the Bolsonaro years. The result, however, was too close to call, and a nervous run-off is awaited. Even if Lula wins (he did win, and is now in his third term as president elect) in the second round, at the end of October, there are enough Bolsonaristas in the new congress and in some of the key Amazon states where the arc of deforestation now sits to make his life difficult. But the return of a Brazilian president committed to rainforest protection in this extraordinary biome, coupled with a Colombian counterpart, Gustavo Petro, who is similarly inclined, is a remarkable development – and there is a lot that both leaders could do. If Lula does win, however, he will need to act fast and with unprecedented vision and determination: the Amazon faces a tipping point in which it could become savannah unless deforestation is very rapidly reduced and global greenhouse gas emissions are immediately mitigated.

Two remarkable books published this year provide inspiration, from different vantage points, about the enormous continuing importance of saving the world’s forests, tropical and temperate. Both books are filled with wonder and with a deep ethical commitment to the innate, intrinsic value of forests, and to the people and cultures to which they are home. Both are also beautifully written and deserve the widest possible audience.

Ever Green, by the late Thomas Lovejoy, a distinguished and much-loved biologist, and John Reid, a conservationist and elegant writer, reads as an extended love-letter to the world’s forests. Every page sparkles with anecdotes and insights. The two authors set foot in all five of the world’s large remaining forests: the taiga, which extends from the Pacific Ocean across Russia and far-northern Europe; the North American boreal, ranging from Alaska’s Bering sea coast to Canada’s Atlantic shore; the Amazon, spanning nine countries in Latin America; the Congo, set across six countries in the wet equatorial middle of sub-Saharan Africa; and the island forest of New Guinea, home to important forests in Papua New Guinea, as well as in the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua.

The book ranges widely and provides compelling insights into the lives of Indigenous peoples and local communities in these forests. It also shows how stark and varied the pressures on the forests are, whether from road building and infrastructure (with roads perhaps the biggest single threat to many of the world’s critical forests, especially in the tropics), commodity agriculture, or timber and charcoal extraction. I particularly valued the thoughtful, analytical chapters towards the end that chart the failures and successes of international efforts to protect forests, including the notion of industrialised countries transferring money to countries with forests to support and protect them, and how the global climate change regimen initially failed but has now at least partially succeeded in recognising the vital role of global forests in climate change mitigation and adaptation. As does Tony Juniper’s Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth’s Most Vital Frontlines, published in 2018, Ever Green leaves the reader with an extraordinary insight into the value of these forests, and a pressing sense of their richness and variety.

The cause of campaigning to save the world’s tropical rainforests would certainly be enhanced if the nations doing much of the campaigning – and not similarly endowed with such natural bounty, such as the United Kingdom – would demonstrate a genuine commitment to the protection of their own remaining ecosystems. The inspiring writer and campaigner Guy Shrubsole, author of the best-seller Who Owns England? turns his attention to the temperate rainforest of Great Britain in The Lost Rainforests of Britain. On moving to Devon a few years ago, he discovered the wooded valleys, rivers and tors of Dartmoor, and the fragments of what remains of a rare and internationally important habitat; home to lush ferns, beardy lichens, pine martens and pied flycatchers. His book is a brilliantly structured and compelling odyssey to understanding these forests: their ecology, their stories, their variety, and their future.

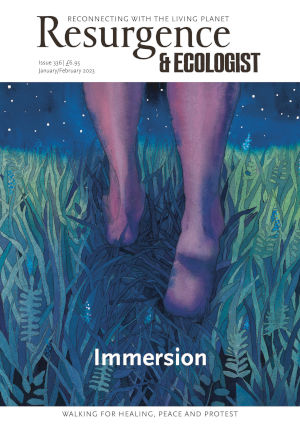

Shrubsole immerses himself in these landscapes, from the Atlantic oakwoods and hazelwoods of the Western Highlands and the Lake District to the rainforests of Wales, Devon and Cornwall – some of the most beautiful places I’ve seen. He discovers a nation that loves these ecosystems: an online Guardian article of his garners 200,000 views, while an interactive map and blog (lostrainforestsofbritain.org) harvests enthusiastic submissions of much-loved oases of temperate rainforest from aficionados around the land. The book closes with a clear-sighted manifesto for a nationwide effort to bring back Britain’s rainforests, encompassing public policy, investment, political will, legal protection, farmer support, subsidy reform, and citizen action. I’m sure many readers will be inspired to support this, especially at a time when the government appears hell-bent on pursuing a more destructive approach.

How, ultimately, will these forests be saved? One conclusion from both books is that, fundamentally, the whole of human society will need to come to treasure them, and to configure itself to protect (and restore) them in perpetuity. This is an ethical project, first and foremost, even if it is also a technical, financial and political one. Fortunately, many Indigenous peoples who still live in the forest have shown us the way. In Ever Green, the authors quote a Marubo Indian from the Javari Valley in Brazil: “The forest is part of our family. When we look at the forest, we don’t just see forest. We see lives. Lives that need us just like we need them.” At this late stage for humanity, we had better heed their wisdom and redouble our efforts. These two books guide us with devotion and skill, and their authors deserve huge credit for raising the flag once again in such generous and inspiring ways.