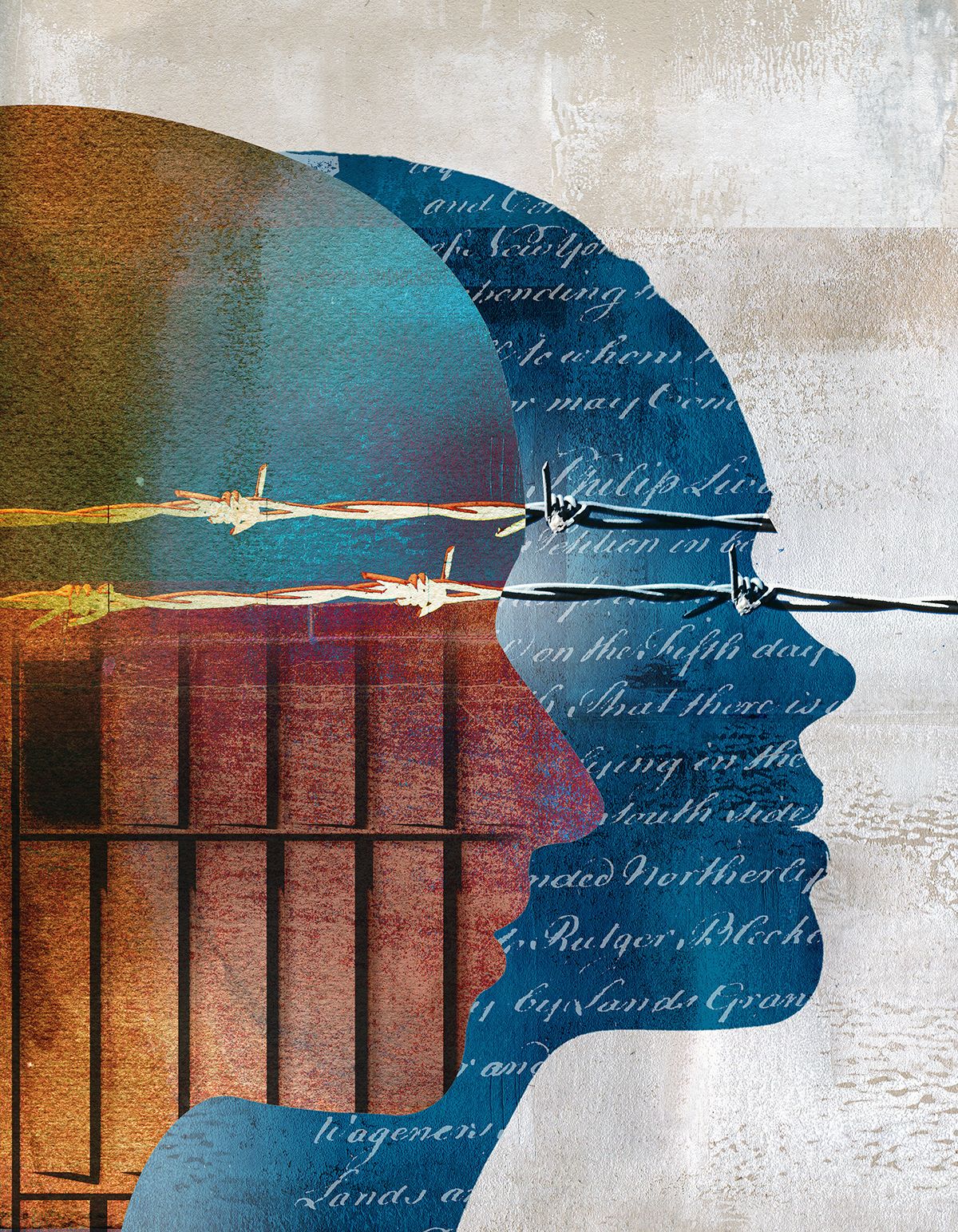

What’s the lived experience of a short spell in prison? For an environmental activist sentenced to nine months (reduced to six because of a ‘guilty’ plea) for resisting state power, and fighting for a cleaner future to avoid the worst ravages of climate change, how does it fall?

Three jails, nine cellmates and two and a half months’ jail time is no big thing – it’s a brief stint. In Iran or Mexico, you’d be looking at 100% worse conditions, crammed cells with higher tariffs, and possible death. Being brought up in a liberal democracy with all the pros and cons that can offer – I grew up in a single-parent family on Essex council estates in the 1970s – doesn’t change the underlying stresses and strains of being banged up in A Cat and B Cat prisons.

I landed at HMP Belmarsh as a remand prisoner. My spur was peopled by serious individuals, most doing long stretches, lifers. This was scary and adrenaline-inducing. House blocks have a fair number of young gang members. As a first-time prisoner, and in for climate, I was pond life. I would hold eye contact hardly at all – I just wanted to be on the down-low, do my time and get out. Most of the time the floor looked good to me.

On the yard each day I talked to no one and just did my workout routines with no fuss. But I made pals in the end and came across people I’d be indebted to: kind men with fellow-feeling who would put themselves out for you at the drop of a hat – once, of course, they knew you were on the level.

In HMP Wandsworth I was on D wing for six weeks: hectic, noisy, violent – you name it. Against the ground floor cells the scraps would mount up for rats the size of cats as periodically the rubbish spiralled down from the upper floor windows. With the bunks (two-man bang-up) abutting the perspex windows, you lay on your bed day and night with the critters gnawing just feet away at the polystyrene food containers and assorted goodies dropped from up high.

In prison stereotypes are shattered, and behind book covers are people who’ll look out for you. Silver teeth, scars, light skin, dark skin, Muslim, Christian: it all means nothing. People are people behind it all – pacing their cells, in tears at times, general states of frustration.

Getting knocked down to ‘basic’ for refusing to transfer prison – they made me go in the end, of course – I was desperate for a radio. I asked a prisoner on cleaning detail, thinking he could put the word out, but he simply told me the chaplaincy should be able to get me one. That kind steer saved me days of chasing down something I was never going to get. I gave him a vape in thanks. “You don’t have to do that,” he said. “I know, but I want to,” I replied.

That’s kinda like what prison’s about – mutual aid in action.

As for family and friends, it’s a huge concern for them, plus an inordinate rise in workload, especially when children are added into the equation. And talking of children, a cellmate at High Down, a star guy, answered my moans about daughters being off school and messing about because of no discipline by saying, “Your child is messing about because she misses you. Nothing to do with discipline or being naughty. Just plain and simple missing her dad.” Prison gives you that mighty character trait common-sense wisdom. Having patience and time for reflection is of course a necessary evil/good, depending on how you look at it.

Activists might find the whole idea of prison a barrier to action, or perhaps it’s not an immediate concern, but in terms of brass tacks, yes, you can normally get books sent in. Reading by poor light in the cell can be tricky, however, especially if your cellmate doesn’t want the strip-lighting on because maybe he sleeps in the day and watches films at night. Yes, you can ask to be moved from a cell if you feel the need. This can take time and will need careful consideration by you first, with a sympathetic screw on hand. And you can choose your food from menus of various standards. HMP estate has varying qualities of grub in different public/private prisons – HMP Belmarsh wasn’t great (usually rice, potatoes and overcooked vegetables, or very scraggy chicken or beef if you’re partial to meat). HMP Wandsworth was OK, and the same goes for HMP High Down (resettlement jail Cat C), where you could score chips and beans.

I was asked to write about the migrants you meet. Well, you tend to find they would rather be in detention centres, which run a much more open regimen. Having shared a cell with an Algerian and an Iraqi Londoner, I can understand frustration over being held past your sentence, on ‘immigration hold’. Obviously the skewed justice system will seek to deport people convicted of crimes and with revoked residency orders. My Algerian cellmate asked, “How come you can come to my country with a plane ticket, but I can’t come to yours with one?” No answer to that. It is a ‘no borders’ argument.

In conclusion, as a direct action activist, I follow in the footsteps of people who have done a lot, lot more – frontline activists helping oppressed people, from Rojava through to Papua New Guinea, for example. And campaigners who have put their lives on the line for animals as well as planet – people like Keith Mann and Mel Broughton/Brown, who served long prison sentences for stopping the cruel and inhumane treatment of voiceless, sentient beings.

In answer to the question whether I would have done the same had I known the sentence: yes (but I would have prepared my family better). Prison is tough – at HMP Belmarsh my cellmate said you are one step from death. If you can ride bang-up and the control that is put on you, it’s doable. There is kindness from prisoners that is unbelievable. In chapel on Sunday everyone’s prayers are for other people, not themselves. Prisoners are resourceful and have oodles of common sense. Try cooking a pukka meal using a kettle – it takes practice.

Wrapping up, the ecological necessity that drove my actions is at a higher level than it was when I landed at His Majesty’s pleasure. Solidarity to frontline activists fighting for global decarbonisation and a just transition to a renewable future for all beings.