We talk a lot about how to make tree planting sustainable, and modelling the way the world might be in years to come is part of this. From NGOs planting in deforested areas to rebel gardeners planting in wild places, everyone wants to plant trees that will survive.

Many tree-planting programmes (often those with generous government funding) will consider climate modelling in order to work out exactly what to plant where, and one well-known organisation that is taking the lead in this kind of decision-making in the UK is Kew Gardens.

The charity’s Millennium Seed Bank in Wakehurst, Sussex houses over 2.4 billion seeds collected from around the world. Seeds are stored either dry or frozen and range from threatened species to species sourced from vulnerable climates. Many plants are edible or offer some other benefit to humans, and teams of scientists use these seeds for research.

Being able to learn about samples taken from all over the world is key to understanding which trees will survive where, and what we now know is that maximising the chances of survival also means maximising species diversity. So with this in mind I sat down with the head of tree collections and arboriculture at Kew Gardens, Kevin Martin, to explore how Kew is planting for both diversity and the future.

How do you look after the trees at Kew?

We tend to use a holistic approach. We manage the tree as a whole. We need to have the right soil and make sure it’s as prime as it can be. The soil at Kew isn’t actually that good, because we have sand and gravel, so it’s hard work to keep the collection looking good. We spend lots of time improving the soil, using mulching and decompaction, a fact which always gets overlooked.

Is Kew involved with other major gardens in the UK?

We have Wakehurst, which is our garden in the countryside. They are doing quite a lot of ecology for us. Plus I sit on a collections network for all the botanic gardens in the UK. We will discuss those areas we plan to collect in to make sure we’re all in the same area. We can then ensure we spread genetic material across all the botanical collections in the UK. We work with different botanical institutes and we share material between us. In order to thrive, we all need to work more collaboratively, which is something we’re working more towards.

Does Kew work with any other existing planting programmes, such as those implemented by the UK government’s Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra)?

I have advised Defra, so, yes, we are involved, as are our scientists. GIS (geographic information system) scientists are starting to look at species selection and modelling, so it’s been quite an important collaboration. To give the best advice we can, especially with, say, big businesses wanting to offset their carbon footprint, we are trying to explain that the choice of species that is being planted is key. We can’t just put anything in the ground. If a tree doesn’t survive, it’s not great.

Trees need to mature and will only capture carbon when grown properly. We are encouraging that understanding outside botanical circles. We explain how we are looking at the soil and the ways the soil affects trees, as well as which species grow and thrive in different places.

How do you try to ensure the trees you plant will survive?

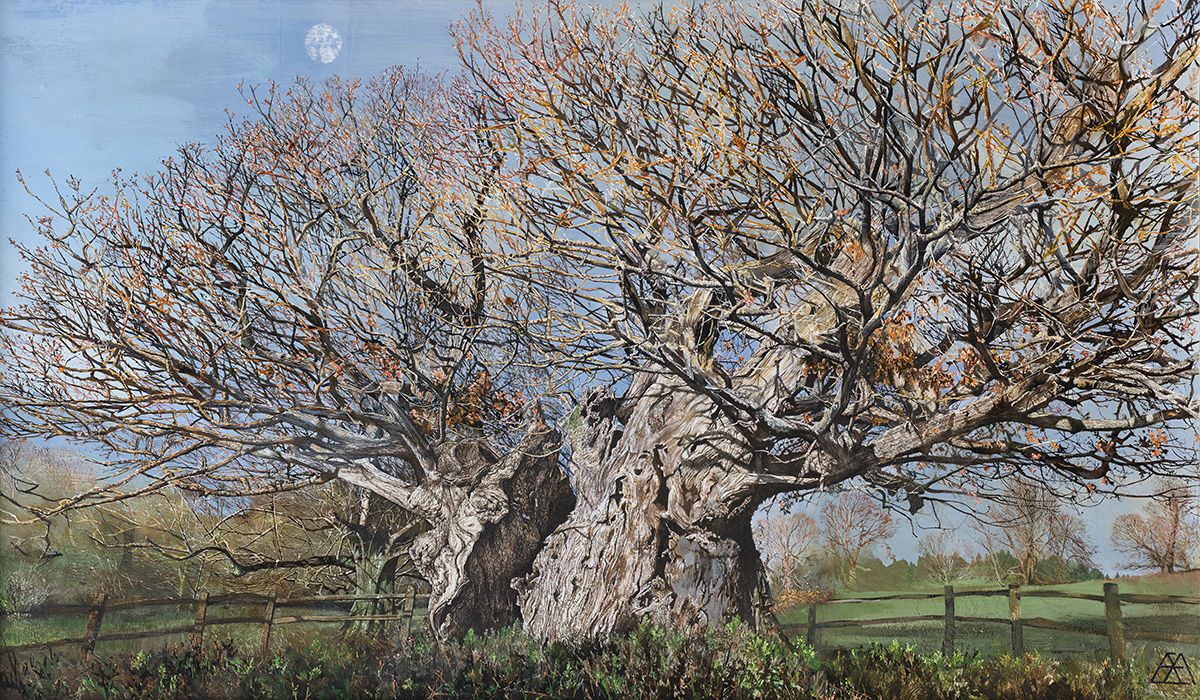

We work carefully with our species selection to get it right. Heritage English oaks and ash are both in decline. Disease, pests and pathogens, we now know, are induced by environmental stress, so we are looking at species like maples and hornbeams, which grow over a large distribution all the way out to places like Iran and Azerbaijan. We will try to map the climate appropriate to these trees in order to protect the English heritage landscape. We are also looking at collecting oaks from the south of France. Their genetics have changed in the heat, so we need to collect the same species from different climate zones in order to protect the species in the south-east of England.

Common beech (Fagus sylvatica) is under threat and is really suffering. Over the next 10 to 15 years we will lose a lot of mature beech trees. We need to look at where else this species is growing, for example in Crimea and other dry ranges in the Caucasus. We’re already trying to get seeds from dry areas so that we can grow them and test them here to see if they would be better adapted. Oriental beech (Fagus orientalis) grows in the Caucasus, both in a drier range and at a lower altitude. Common beech grows a bit higher up, but there is a middle belt where both trees grow together. We can collect seeds from that area, where we know the common beech grows on the edge of its range, and hopefully bring it back to the south-east of England, and then it should have more tolerance to drought.

Do common species have fewer legal restrictions?

We still have to get permits, but that’s more to conserve our English landscapes. I love to plant rare and interesting species, but we would lose the heritage landscape if that’s all we did. If the National Trust lost all the common beech and English oaks on its properties, we’d lose all the Capability Brown-designed gardens.

Does the UK have a lot of the oak trees in the world?

A lot of the trees in Europe, for sure. We need to safeguard those trees. They have to be English oaks by taxonomy and name. Lots of English oaks come from Italy, historians say. The same applies to the elm. When the Romans started moving about, a lot of trees were brought here.

Is the UK planting more oaks generally?

Well, it will be interesting moving forward, especially with people offsetting carbon, but there are problems with planting oaks. In London we now have the additional hazard of oak processionary moth. The caterpillar came over in 2007/8 as a Dutch import. The affected trees were planted two miles up the road from Kew on a development site. The moth larvae live in groups and have toxic hairs. When the hairs come into contact with livestock or humans, they can cause massive irritation. The moth has spread quite far out of London in just a decade. It’s right outside the M25 already and going into Hampshire and Berkshire now. People don’t want to plant oak, as they will now have to do loads of maintenance to control the caterpillar numbers, including spraying the leaves.

How important is species diversity?

The more diverse any collection is, the better for everyone. We are always looking ahead –10 years, 20 years. Canker stain (which destroys plane trees) has now travelled through to Italy and Central Europe. If we get that here, we’ll lose the London plane trees. Imagine London without the London plane – not just the look of the place without them, but then with heat rise… But at the moment I would say we’re managing this spider’s web so that we can plant, grow and keep a sustainable collection.