Living in a city can bludgeon the senses, particularly if that city is Delhi. Twenty years in one of the noisiest, speediest, most polluted cities on Earth had left me hearing-impaired, Nature-deprived and hungry for the ever-shifting shades of green of the English countryside. Happily, the place I have ended up living in hits the absolute sweet spot for recovering chlorophylliacs like me: in south-west England, on the border of Somerset and Devon, close to the beautiful Blackdown Hills.

When I first heard about Karen Stead-Dexter and her work using raptors as therapy birds, I was intrigued. The idea that spending time in Nature is good for our mental and physical health is now mainstream, but what I was hooked by was not the soothing balm of forest bathing, or the stress relief of the petting zoo, but the visceral thrill of proximity with a wild other intelligence – with talons.

There’s nothing quite like being close to a powerful animal to get the blood up, the skin tingling, the eyes alive, the senses on high alert. It is, after all, dangerous: those talons are sharp, those wings powerful, that beak can do some damage.

As I drove to my first therapy session, I was not sure what to expect, but two words kept coming up for me – clarity and connection. Could an owl or an eagle really help unmuddle my mind or banish my feelings of isolation? It seemed unlikely.

As I would learn, Stead-Dexter is many things: falconer and therapist, environmental scientist, Earth-lover, moon-gazer, shape-shifter, herbalist. She laughs a great deal, and beneath her frizz of hair her eyes sparkle with something like mischief, something like joy. “I wouldn’t call myself a healer,” she says. “I’m more like a teacher – or a facilitator. And I connect people, whether that’s to themselves, or Nature, or the animal. I’m just there to remove the cloudiness. It’s up to that person to step forward and do the work. I’m there just to make things a bit clearer for them.”

She works with, at present, eight birds of prey, all born in captivity, five of whom were rescued and rehabilitated by her. The largest, Rosie, is a magnificent 35-year-old European eagle owl, 2½ feet tall, weighing eight pounds, with a wingspan of more than six feet. She has been with Stead-Dexter for eleven years now, but had never previously been handled or flown, and was in a terrible state when she first arrived. Beneath her magnificent ear tufts, her eyes are the most extraordinary bright orange, with black irises in the centre. The swoop of the tufts gives her face a sort of frowning ‘headteacherly’ intensity – as though she is looking right into your soul.

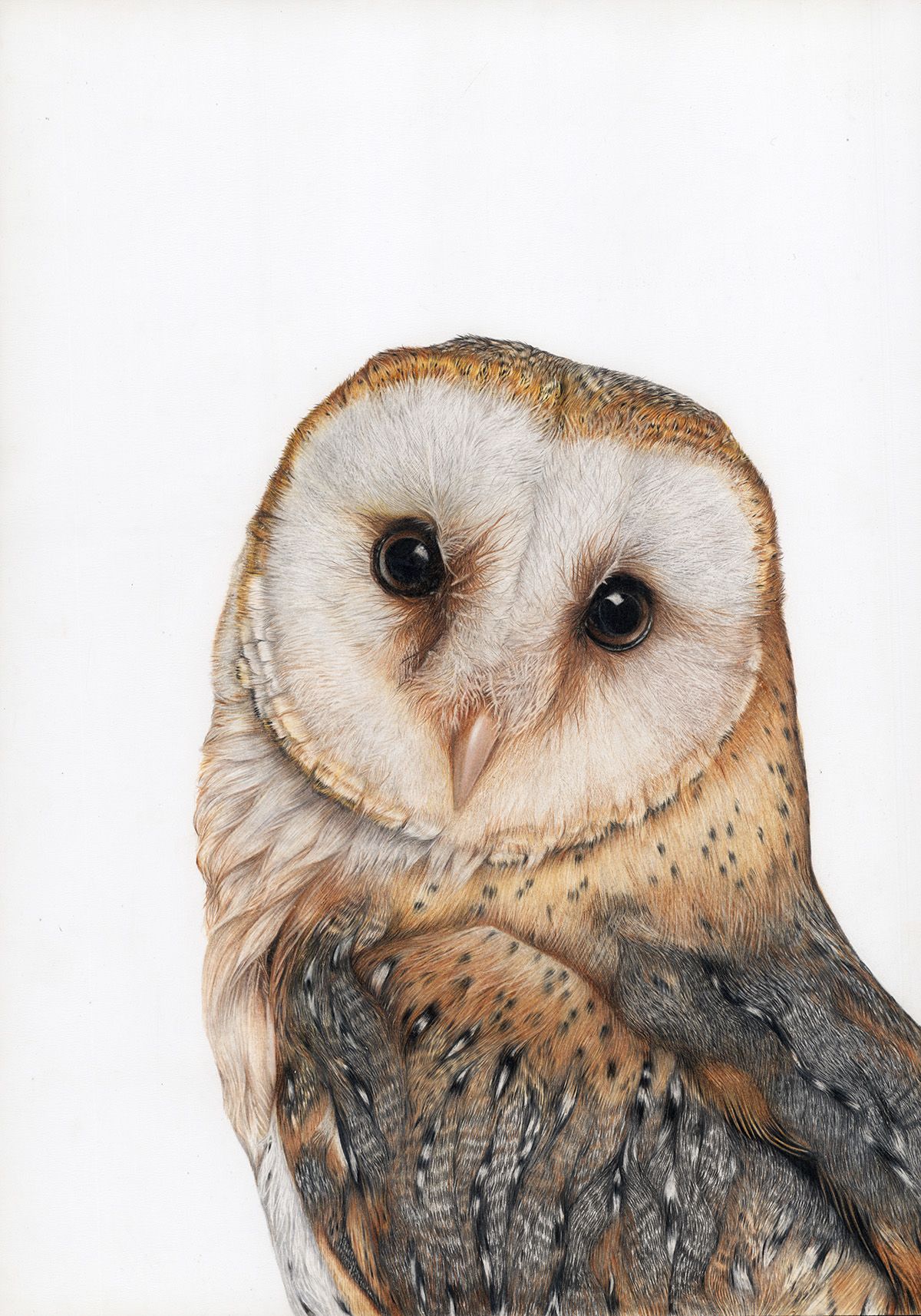

The smallest of the birds is a dainty little kestrel called Inca, just 6oz in weight but whose size belies her absolute focus. Kalil and Khan, the gyr-saker falcons, are larger than the kestrel and are like single-pointed arrows of pure concentration. Using a police speed camera, Stead-Dexter has clocked Khan in a downward swoop topping 182mph. The pads of his feet help to cushion the impact when they hit their target. But the bird who ‘chose’ to work with me that day was George, a barn owl.

His face is a broad, heart-shaped disc, perfect in its symmetry, pristine white. The feathers radiate from each dark, intelligent eye, and down to the narrow beak, like a polished sliver of rose marble bisecting the two halves. His chest and legs are also ermine white, his back and wings flecked and patterned in gold, orangey-brown, black and white. All of which is to say: he is breathtakingly and heart-stoppingly beautiful.

As Stead-Dexter talks about the morphology and physiology of owls, I stand, transfixed by this creature on my gloved hand. It is like a dream: vivid, laden with a strange electrifying energy, so alive with symbolism that it is practically shouting. I look at this feathered being on my arm, and then look out into the world, and it is transformed – the same world but through an owl’s eyes. My hands inside the leather glove flex and move in tune with his talons. I turn my head to follow his gaze, tilt my ears to catch the telltale rustle in the leaf-litter that pinpoints exactly where the beating, bloody heart of his next meal lies.

When Stead-Dexter talks about the barn owl’s amazingly acute hearing but its relatively weak eyesight, my own tearful frustration that I hear so little and miss so much is gently lifted away. “What other senses can come to the fore to make up for your hearing loss?” she says. “Look at George.”

After an hour with George, I am sensing everything more acutely, alive and aware of the air on my skin, the taste in my mouth, the lift and fall of each breath through my body. The session leaves me ravenous, exhausted, uplifted and deeply happy. I also seem to be hearing a bit better. Owl magic? Or is it just that I’m paying more attention to the world?

There is, of course, a direct correlation between the quality of an experience and the quality of the attention that you pay to it. As I tune my ears to the natural sounds around me, they seem to subtly amplify in response, as though rising to meet the longed-for touch.

When we employ Nature as a therapist, are we simply projecting our own ‘stuff’ onto the unwilling and certainly unwitting natural world? Is Nature – this bird, that tree, this weather, that mountain – simply a mirror, held up to reflect back to ourselves what we want (or don’t want) to see? That worldview leaves objective reality nicely untroubled by animism, and us in our comfort zone, with our busy little unique human minds the only things making meaning in this world.

But what if we view Nature less as a mirror and more like a window? A portal through which to explore and discover the world so much more than ourselves? This seems like a more fruitful way of thinking, and a way of breaking through the unrelenting anthropocentrism – and loneliness – of the mirror-world.

The sunlight catches the surface of the falcon’s black eye: a whole, bright and brilliant star contained in its depths. Perhaps the natural world is neither mirror nor window but more like a pond or a lake. You can see yourself reflected there, catch your eyes looking back at you. But refocus a little, and you can see the water itself, its scintillating dance, the quality of wetness and weight, the creatures that move through it. Focus again, and you can see through the water to the bright pebbles and sand at the bottom. Look again at your reflection, and you’ll see the sky behind your head, the light dancing through the leaves in the trees behind you, the swift flick of a bird darting across, and you’ll see yourself not as the isolated subject, suffering and alone, but as of a piece with the sensing, vibrant, living world, sensing and sensed by a host of Others – furred, feathered, creeping, swimming, flowering, growing. Flooded with clarity and connection.

There’s a lovely phrase in the English language, when you talk of something ‘bringing someone to their senses’. As if a jolt were needed to reignite the connection between the mind and body, or the body and its environment. Philosopher David Abram describes the body as the “mind’s own sensuous aspect” – and it is this magical, intimate integration, this healing of the rift between our bodies and ourselves and that which nourishes and sustains us, that Karen Stead-Dexter and her birds bring into play by inviting us outside to just be.

Anita’s article will be the focus of the Resurgence Readers’ Group discussion on 17 July 2023, 7–8pm. For more information and to book a free ticket: www.tickettailor.com/events/theresurgencecentre/926789