The Toyota stops. Mike Anderson, our guide, gets out and takes up his .375 calibre rifle. We form a single line ready to move out into the sunlit African wilderness. We want to track a lone bull elephant and find wild lions. I am on safari in the Tuli Block National Park in Botswana.

We take a few steps forward in the fresh morning heat. But I find my attention drawn to a mid-sized Marula tree. The branches are laden with small, bright yellow birds, their newly constructed nests hanging down like fruits. I decide to hang back alone at the tree. What I see next changes my perspective on Nature, and our role in Nature, in a profound way.

Safaris are not my thing. But Natucate, which specialises in educational wilderness experiences, offered to host me in southern Africa for a week. We would be based at a temporary campsite in a remote area at the border between Botswana and Zimbabwe. England (where I live) is one of the most Nature-depleted countries on the planet, and here was a chance to experience wildlife in all its glory, almost untouched by human development.

I wanted to hear what Nature had to say. I know the danger of human beings projecting our social values onto the natural world, naturalising and normalising our prejudices and privilege in the process. But I decided to take this opportunity to project my ‘progressive’ values onto a rich natural environment and to find out what narratives might emerge.

I arrived bleary-eyed at Johannesburg OR Tambo International Airport, South Africa. Hours of broken roads followed. We stopped overnight close to the Balule Nature Reserve within Kruger National Park. Anton Lategan, managing director of EcoTraining, which was facilitating the trip, hosted us for the evening. “Nature has proven what works over time, so let us learn from it,” he advised.

The following day we drove to the Botswana border. A small blue-cage cable car took us, two at a time, across the Limpopo River. Mike was waiting on the other side, with green eyes and a Stetson hat, ready to take us deep into the wild.

Exceptionally heavy rains had closed our road. The planned three days of tracking by foot was cancelled. But we were still camping out in the bush, miles from any human settlement. We took a three-hour detour; an s-shape that left us not far from where we began.

We entered the African bush at 6pm – to be greeted by a vision of utopia.

The rains had watered an ever-present carpet of light green foliage, and everywhere there were bright yellow flowers. The golden sun, the rolling hills. The evenly spaced shrubs and trees. I could see a joyful springbok, a suave zebra, a gentle wildebeest and a temperate elephant. A lone giraffe watched the sunset. These animals were familiar to me. But what blew me away was the totality.

“The paragon of animals!” We found ourselves surrounded by huge flocks, herds and troops. I could see a hundred springboks assembled together, vigilant but calm. And dozens of zebras, peacefully chomping grass in their striped finery. A troop of thirty baboons passed through. Before human intervention, these animals were even more numerous. Nature is abundant.

But the thing that surprised me most was the fact that the animals seemed so relaxed. There was bountiful water and grass. Animals live in their larder, food constantly within reach. The herbivore and omnivore species before us were all jumbled up together, criss-crossing and congregating, totally at ease with each other. The carnivores – lions, leopards and hyenas – had left tracks but were conspicuous by their absence.

I spotted a lone male wildebeest hanging with the zebra herd. Mike explained that some animal species actively support each other. The wildebeest is warned of predators by the sudden movement of the ‘rival’ zebra species. Fascinatingly, the zebras mow down the long chaotic grass with their agile lips, leaving an even-cut lawn for the blocky wildebeest. There is symbiosis at every scale of life.

The totality is the complex interrelations between all of the species, the entire ecosystem. It includes an incredible variety of grasses, fungi, flowers, trees, insects, birds and animals large and small. Each ecological domain deserves its own safari. And it’s all here, right in front of our eyes. I feel like I have seen and learned so much, and we are yet to arrive at the camp.

That night in my tent, safe from the camel spider and scorpion, I reflect on what I have witnessed. There has long been discussion about how much we can learn from Nature, and from natural processes. Herbert Spencer pressured Charles Darwin to insert the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’ into later editions of On the Origin of Species and ever since society has been discussed through the lens of scarcity and competition.

The male elephant goes into musk, is overwhelmed by testosterone, and again takes control of the female herd. The alpha baboon is the biggest, the toughest. He fights off any rival and is rewarded with coitus – and offspring. But the stories we tell of the animals have always been stories we are actually telling about ourselves. The male is the subject with agency: the female and all of Nature are his object.

But this is simply not what I saw during our safari drives over the following days. In fact, I saw evolution from the standpoint of the female.

Springboks mostly live in large herds of females. The males are cast out to the periphery at adolescence. The females select which male can rejoin the group at mating time, and in doing so unwittingly choose the genes that will continue.

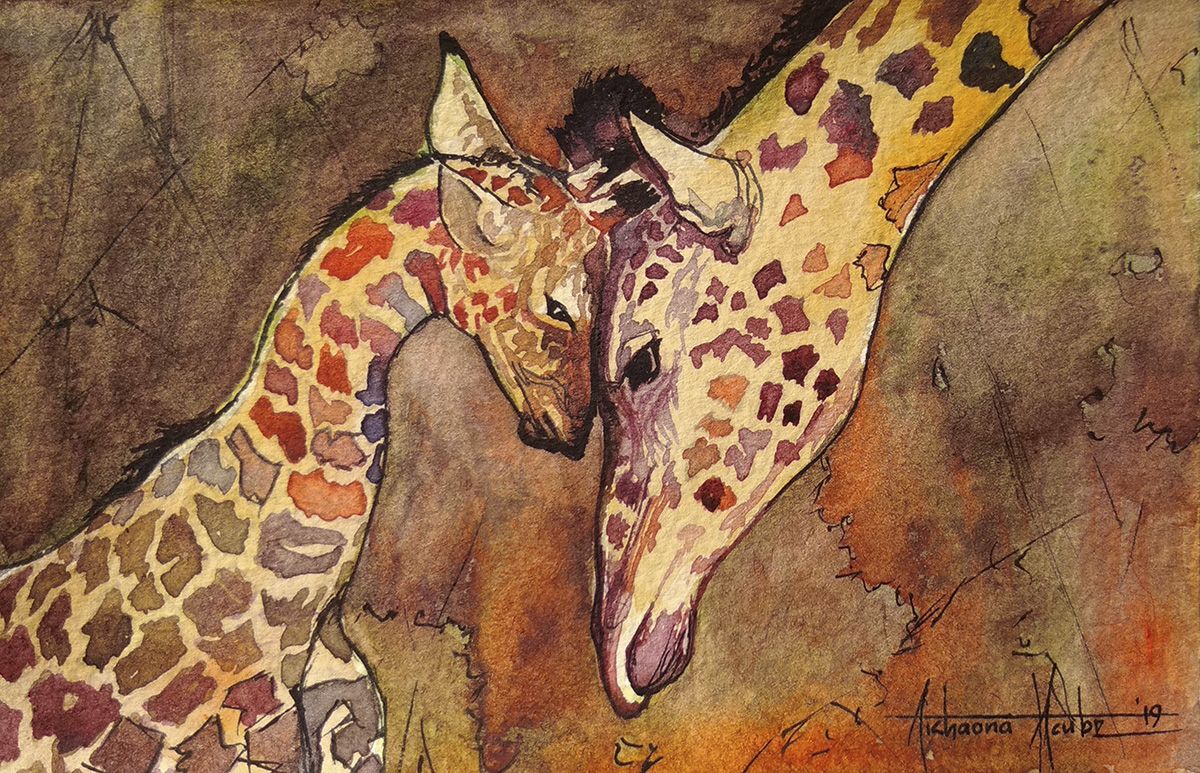

The same is true of the elephant. We watched a bull shower himself in mud and water, chew the grass, and walk alone into the bush. Solitary, apparently content. Males do sometimes group together. The females live in herds their entire lives. They often allow only one adult male into their tribe. His presence allows the younger adolescent males to moderate their hormones and behaviour.

Some while later, we find ourselves flanked by a huge troop of baboons, wandering across the land like a company of Shakespearean travelling actors. The females are the heart of this long caravan. Some have tiny infants clutching to their bellies. Mums gallop along with little ’uns on their backs. They tumble in the grass, playfully. They chatter. I see a juvenile pick a mushroom, take in its smell, and then toss it into the bushes. This is where the action is.

And then there are the alpha males. They remain on the fringe of the group. They are isolated, silent, alert. No one pays them much heed. They are older, tougher, roughed up. They remain stoic as they survey the horizon. They know that if a predator attacks, they could be eaten – or survive with agonising injuries.

Where others see patriarchy, I see matriarchy. And academics agree. Cynthia Moss of the Amboseli Elephant Research Project has said: “Our studies show how absolutely crucial matriarchs are to the wellbeing and success of the family.”

During our last evening drive we met the largest herd of elephants so far. There was an adult, then a juvenile and then a baby. The infant was no more than a week old. It was pink behind its ears and had scant control of its trunk. The baby was protected under the mother. It started to suckle.

The sun set. The zebras were velvet-red in the evening light, their stripes even more stylish. They have tiny ones, too. The new-born wildebeests are diminutive and as tough as old boots. There are baby bush-pigs.

For so many living things most of their activity is dedi-cated to reproduction through the cycle of sex, birth and nurturing. The species that is ‘fittest’ is the one that guarantees the success of the next generation. Life has been defined by philosophers as autopoiesis – the act of self-making. This is true for the individual, for the species, for the ecosystem.

There is infinite variety in Nature. We choose which species’ social structures to emulate, and which to ignore; and so we make human choices. But there is one thing that is true for all of Nature. Every living thing is busy in the act of producing and reproducing itself and its offspring. I am not saying everyone should have a child – I personally have none. My point is this: humans as a species need to concern ourselves with the welfare of all future generations.

It is our final day on safari. This is our last chance to track a lion in its natural habitat. But just as we are about to start, I abandon my group to spend half an hour alone watching a humble weaver bird busy among the branches of a tree.

The male of the species spends three days building a nest: a wicker sphere, hollow like an egg. The female, according to local lore, will inspect the nest. If it is deficient, she will reject it. The male will then start on the next nest, building as many as 25 in a season. As a community, weaver birds create hundreds of tiny homes in the branches of a single tree.

The weaver bird builds his nest among a community of equals, amid abundant materials and food. I think of the orangutan, the ‘person of the forest’, building her nest in the forest canopy. And the capacity of humans to build and rebuild. The world we weave should be a gift of plenitude created by the present generation for the enjoyment of those who will come next.