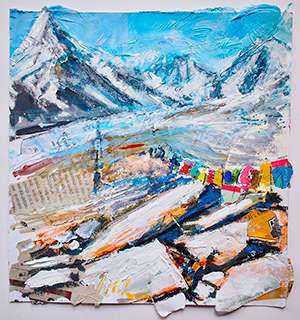

I recently attended a conference in France, near Mont Blanc, where I was invited to comment on a discussion about the beauty of experiencing what mountains have to offer – how they affect people who have the opportunity to ‘enjoy’ them. Attendees at the conference, many of whom are avid mountaineers or lovers of the joys of experiencing wilderness, spoke to the spectrum of positive impacts that being in mountainous landscapes confers: exercise, fresh air, a closeness to Nature that cannot be explained by mere words, bonding with peers in ways that are often not part of daily life, a sense of freedom and even a meditative and spiritual effect. The discussion moved towards the importance of finding ways to make mountains more accessible to those without the means of exploring them.

My response to this somewhat broke the reverie: is it not time that humans consider leaving mountains – and more broadly wilderness – alone? Is it not time that humans, who now number eight billion, act intelligently to enable a managed retreat from Nature? Don’t we already know from our collective scientific data that the assault on Nature and the biosphere is a direct result of our inability to respect limits and boundaries in search of economic growth, to feed our curiosity, or to satisfy our desire for pleasure? And is it not the most privileged of us who are the biggest culprits?

The time has come to start the process of respecting what we do not quite understand, and instead enjoy mountains – and all aspects of wilderness – from afar, just knowing they are there. We have been justifying further incursions with dubious arguments about the need to get in touch with Nature – we have literally been in touch with Nature for too long and have trampled upon it irreversibly in many parts of the world – or to conduct more research to understand it better for the purpose of protecting these places from “other, less caring humans”. We have to honestly acknowledge that we already know and have had enough experience of Nature to act to protect it through a managed retreat, and not from just the most precious regions of the world, but also from many areas where our presence does not add any value to Nature or humanity. We need to completely recalibrate our relationship with Nature and the wilderness with regard to our preoccupation with the notion that we have a right to enjoy it like any other commodity. And that means rejecting the idea that just because one can afford to travel to places of natural beauty, one is entitled to awe and pleasure.

This speaks to a broader issue, which is the relationship that many modern and wealthy societies have with Nature: to exploit it, to seek self-gratification through it, and to want to own it, even if only temporarily. It is a contradiction that is steeped in outmoded ways of seeing the world, in convenient denial, through elaborate justifications that enable an elite minority to trample and pave the way for abuse and destruction, while also appearing to be ‘lovers’ of Nature.

In the west, many factors have contributed to this status quo. Most obviously, the rise of capitalism, but also, historically, the Enlightenment belief of exploiting Nature for humankind’s betterment and the historic Judaeo-Christian rationalisation of creating dominion over Nature as per certain (but not all) religious thought: “Go forth and multiply”; “Everything that lives and moves will be food for you.” Collectively, this has cultivated the need to dominate wilderness for a sense of conquest, or the desire to escape and seek refuge away from society.

With all the evidence of human transgression of natural limits (for example, the nine planetary boundaries), it is time to have an international effort to foster new levels of self-awareness surrounding the relationship we share with Nature, especially if we are to preserve ecosystem integrity and not fall into neocolonial traps – even those that arise from a seemingly positive place, such as seeking to enjoy mountains and the wild. A retreat from Nature and wilderness is now overdue.

Cultures across the world have maintained spiritual or holy relationships with mountains and the wilderness for thousands of years. The First Nations of North America are renowned for such relationships, historically having practised a communal approach to land ownership that was starkly at odds with the capitalist private land ownership model of European colonialists. In northern India and Tibet, Mount Kailash – near to the source of the Indus, the Sutlej, the Brahmaputra and the Karnali rivers – is sacred to four religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Bon) as the spiritual centre of the world, and attempting to climb it is therefore forbidden, an edict that stems from a place of deep respect.

However, the value placed on mountains by communities is not always respected by those from richer societies. A significant point of origin lies in colonial conquest and the establishment of settler communities, who by definition were trespassers and had no respect for local traditions and the beliefs of Indigenous communities. There are two poignant examples: Uluru and Sagarmāthā/Chomolungma (colonially renamed as Ayers Rock and Mount Everest respectively. Uluru, in central Australia, is sacred to the Anangu, the First Nations peoples of the area. They do not climb the monolith. Yet ever since white settlers arrived, tourists (including the late Queen of England and the current King) have summited – despite pleas to prevent them. Fortunately, climbing was eventually banned – but not until 2019.

Climbing to colonial heights

Moving to the China–Nepal border, Sagarmāthā/Chomolungma (meaning ‘Goddess of the Sky’ in Nepali or ‘Goddess Mother of the World’ in Tibetan), is sacred for many surrounding cultures. Yet many, particularly from the west, feel entitled to seek ‘awe’ from – or even ‘conquer’ – this mountain using their capital, amassed in nations that have systemised the process of exploiting Nature, to purchase travel, equipment and guides. The Sherpa bear the burden of much of this risk by fixing ladders, carrying oxygen tanks, and setting up camps with food and drink. There was even a Sherpa strike in 2014 due to the unreasonable demands of foreign climbers relying on them.

Beyond being culturally disrespectful, attempting to force human presence into mountains and other places of natural beauty will inevitably lead to environmental impact: in 2019, the Nepali government cleaned 11 tonnes of rubbish from Sagarmāthā. The climbing route becomes clogged in certain climbing seasons and as a result tragedies occur, yet these are transformed into stories about heroic human endeavours to be emulated, while also typically leaving out the local people who made it all possible – often repeatedly taking life-threatening risks simply to eke out a living – and the adverse impact these misadventures have on local traditions and customs.

Rethinking relationships with Nature

In addition to the cultural significance of mountains, respect for orographic landscapes originates from a practical position due to the often harsh environment they present. Yet the appreciation of this aspect of humans’ relationship with Nature is increasingly absent. For example, there is a growing body of people in modernised countries who want to ‘get back to Nature’ as a means to escape the challenges of modernity, but they fail to recognise that for most of human existence, Nature was not simply a place where peace and tranquillity existed by default. Rather, it is only through human excursion and intervention that environments can be manicured and manufactured for our habitation and pleasure. Another example is the vulgar safari tours in Africa where hordes of supposed Nature lovers want to get close to lions hunting and eating other animals, film these encounters from the comfort of their four-wheel drives, and feel they have connected with Nature by having now experienced the cruelty of the animal world.

This disconnect is fundamental to the way advanced societies perceive the modern relationship with environment: Nature has to be transformed into tangible capital or intangible experiences that improve our lives. And in many instances so that people can simply have bragging rights. The intrinsic value of Nature has been subsumed by its instrumental value.

Thus there is an unavoidable irony that arises from the trend of what are now commonplace terms used in the sustainability sphere, such as ‘Nature-based solutions’, ‘biomimicry’, and ‘green finance’. In reality, we have succumbed to oversimplification and are selectively using aspects of Nature that create value for us, most often to either mask or directly enable overconsumption and further exploitation of Nature, while actively ignoring the lessons of dynamic equilibrium, carrying capacity and symbiosis that characterise so many ecosystems.

Even the language we use demonstrates how certain cultures have evolved a transactional relationship with Nature. For example, in the English language, the noun ‘environment’ has its etymological roots in the Old French environer, meaning ‘to surround or enclose’. In this definition, humans are observers placed at an imagined centre, while Nature is something around them: separate, extraneous, and being observed. This is a profound distinction, and – returning to Australia – one that historically did not exist in First Nations languages: there was no concept of environment or Nature, because their culture did not (and still does not, in many instances) separate humans from plants, animals and geomorphology.

In the Philippines, Kankanaey communities in the Cordillera mountain range have a specific word – inayan – that denotes ‘unethical deeds’, including those perpetrated against the environment. Through inayan, communal forest protection occurs, and natural resource use takes place at a sustainable rate.

In Southern Belize, the Q’eqchi Maya refer to themselves as Ral Ch’och’, as people who depend on and care for the Earth.

There are many more examples of different understandings of Nature embedded into language, but their prominence is increasingly at odds with the way modern economy and society operate.

Retreating from wilderness

As we grow increasingly aware that our modern relationship with Nature is – ironically – not the natural order of things, we should not fool ourselves into thinking that facilitating further enjoyment of Nature will remain sustainable with more fantasy discussions about the benign nature of eco-tourism for example, or that it will convince a majority of awe-seekers to decouple from the systems that enable our unfettered destruction of the environment and other cultures and traditions. Instead, it is time to orchestrate a planned retreat from wilderness. Primarily, this must occur at a systemic level: the way our economies and corporate structures are designed to convert the natural resource base into economic capital via a linear model of consumption. This is the only way we can avoid cata-strophic civilisation collapse at the hand of existential risks like climate breakdown, biodiversity loss and the disappearance of Indigenous knowledge about caring for Nature.

However, this systemic change cannot occur without accompanying mindset shifts in societies, particularly richer ones. That means you and me. We must gain the self-awareness to recognise that feeling free and getting a thrill from diving to swim with whales, taking expensive trips to Antarctica to witness the melting of the ice cap, or trekking into the Amazon to ogle Indigenous communities are all part of an entitled mindset that stems from and contributes to the larger disregard we hold for the natural environment.

This is not an easy pill to swallow for many, as it requires sacrificing what we view as a right and an entitlement when it comes to enjoyable and rewarding aspects of our privileged lifestyles. But not everyone can or should seek awe from Nature in these ways. A study in Poland has linked mountainous hiking to eutrophication in alpine lakes, while other studies have demonstrated how scuba diving has damaged Thailand’s coral reef systems and Mexico’s marine environment. It is telling that even these seemingly remote places are being degraded by people who seek the thrill of going where few can or do go.

Admire wilderness from afar. And if you are desperate to seek awe from Nature, do so by finding value in the practice of respecting aspects of Nature in your immediate vicinity. Help regenerate it, minimising your own impact on it, and start advocating for systemic change in the ‘awe industry’.